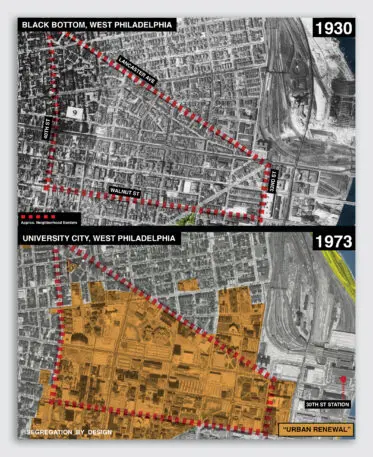

Walking around the north side of Philadelphia’s University City neighborhood, it’s difficult to imagine what stood before the sprawling University of Pennsylvania medical campus, replete with scores of half-empty parking lots and franchise restaurants. But for Segregation By Design, a new initiative that seeks to unearth the legacy of racist planning in American cities, the visual history is clear. What stood before University City was Black Bottom, a thriving Black working-class community whose proximity to Philadelphia’s urban core made it a prime target for the 1950s slum clearance, freeway construction, and redevelopment projects that decimated hundreds of low-income neighborhoods across the country.

Segregation by Design, which takes the form of a blog-style website, various social media pages, and a forthcoming book helps long-time residents and the urban-curious alike visualize the legacy of racist urbanism. The project shows neighborhoods impacted by redlining (a term for race-based exclusionary tactics in real estate), federally funded “urban renewal” projects, and environmental racism. It joins a larger conversation about the ways in which supposedly neutral public planning has disproportionately affected low-income communities of color.

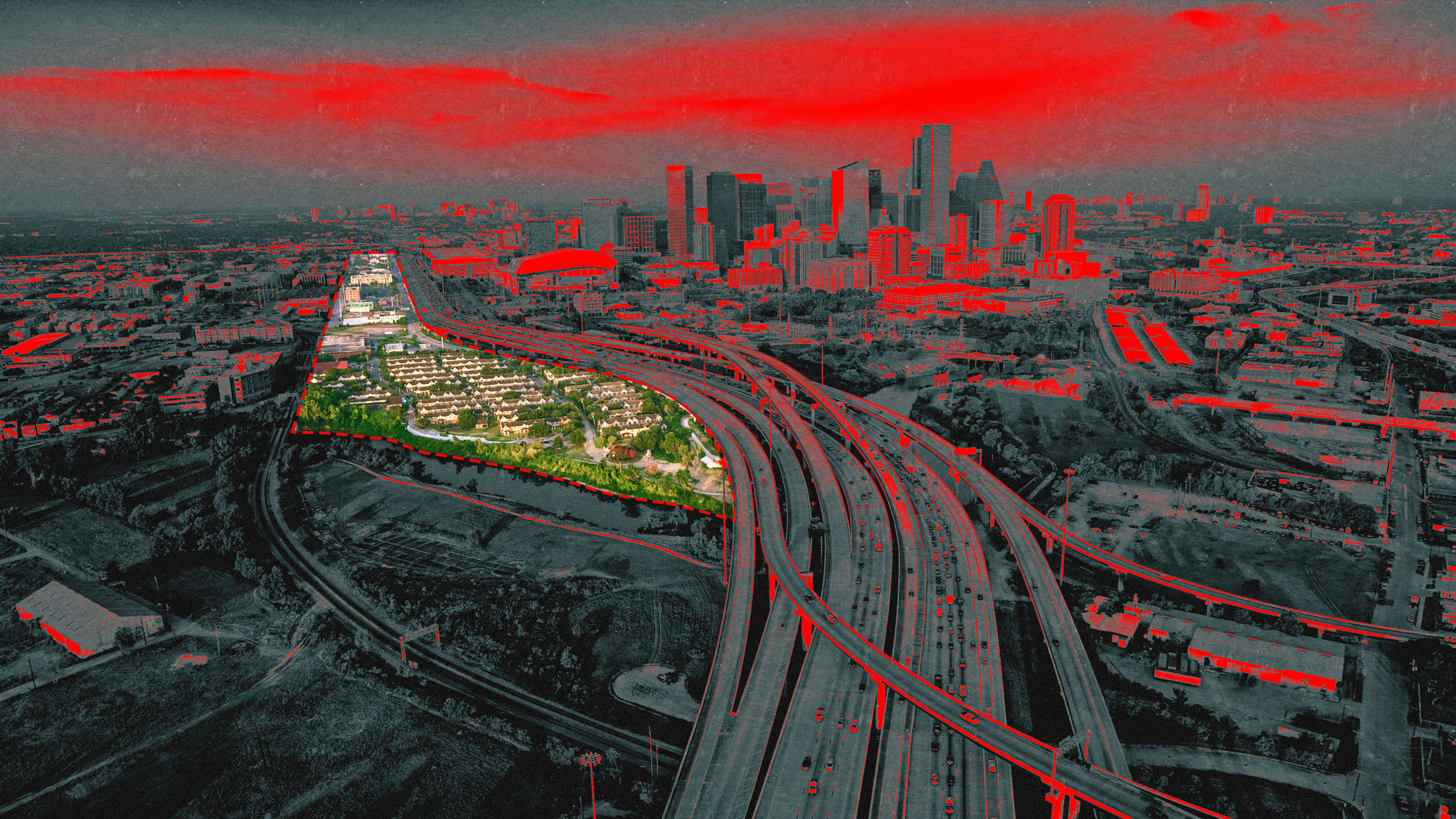

Using annotated satellite imagery, historical redlining maps, and archival photos, Susaneck hopes to profile 180 American cities that received federal funding from either the 1949 Federal Housing Act or the 1956 Federal Highway Act, two pieces of legislation which greenlit devastating and discriminatory infrastructure projects around the country. So far, with funds from a Patreon account and Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture and Public Planning incubator prize, Susaneck has completed 11 cities.

Susaneck shows what Roxbury looked liked through photos like the one above, maps of the neighborhood, and narrative explanations of how affected communities have fought against injustice. Susaneck is hopeful that his work will add a missing visual narrative to a growing urban planning movement that decries car-centered development and seeks to restore and rejuvenate public spaces.

Segregation By Design joins the conversation at a time of unprecedented spending on American infrastructure. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 unlocks over $1 trillion to remake cities with the promise of a better future. While more money is not the only answer to the mechanisms of oppressive public planning, it’s a promising start. For Susaneck and his passion project, understanding urban planning’s racist past is the key to constructing more equitable cities in the future—filled with accessible public transit, pedestrian-friendly roads, and ample public space for all.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.