Grubhub. Uber Eats. DoorDash. These third-party food delivery services bring us everything from mom-and-pop pad thai to Big Macs. Third-party restaurant delivery is an estimated $13 billion business today, and some believe online food delivery in general could blossom into a $365 billion industry globally by 2030 when you roll in all aspects of the market, like groceries and pre-made meal kits.

But in some ways, it’s an industry that’s still in its infancy. Forget the tricky business of the “last mile” of delivering a meal–many companies are still figuring out the first few feet. Most restaurants aren’t optimized to have their food picked up; they’re designed for in-person service. Go into any restaurant today, and you’re likely to see a pile of takeout bags, cluttering the counter. Couriers clog the line beside customers. It’s an organizational mess.

“There’s congestion and chaos created by this new operating model that can’t necessarily fit into the space,” says Tim Young, cofounder and CEO of food technology company Eatsa.

The solution, however, could be simpler than we’d think. It may just be shelves–albeit very high-tech ones that Eatsa dubs “Spots.”

So far, the same problem affects small and large restaurants alike. The core challenge is that restaurants are all designed and operated so differently. As a result, Grubhub and Uber Eats both consult with their restaurants one-on-one, offering best practices and advice to incorporate pickups into each unique space. McDonald’s, following its delivery deal with Uber Eats, has to figure out a unique spot for courier food pickups in every single location (14,000+ in the U.S.!), because there’s isn’t just a single footprint for every McDonald’s location. The company tells Fast Company there’s “no system-wide approach” to food pickup, though couriers are free to use the drive-throughs if they prefer. Such ad hoc improvisation is typical across the industry.

In June of last year, Chipotle began testing a new pickup model, for both customers who ordered ahead online and couriers, too. While you used to have to go up to the counter to pick up a remote order, Chipotle installed a plain, wooden shelving unit, placed near the front door of one NYC location, as a test. Food is bagged up, labeled by name, and placed on the shelf. To grab your order, all you have to do is walk in and, well, grab it.

The test was an immediate hit with a measurable impact on Chipotle’s delivery times–which Chipotle claims are “industry leading.”

“The couriers really like the pickup shelves because it allows them to quickly pick up the order without waiting in lines,” a spokesperson explains. Only half a year later, Chipotle has shelves installed in 1,000 of its restaurants, and plans to retrofit all of its stores with shelves within the next six months.

Eatsa hopes to do one better. The company is known for its automated, self-serve quinoa bowl restaurants in San Francisco, and it now licenses much of its ordering and expediting technology to others in the food industry.

Its new product is a small, modular shelf dubbed the Spotlight Pickup System. It’s a minimal U-shaped shelf, powered by a digital back end that can plug into services including Grubhub or Uber Eats.

“You see the orders stacking up on the counter in your average restaurant,” says Young. “For operators, now there’s a very clear place to put them.”

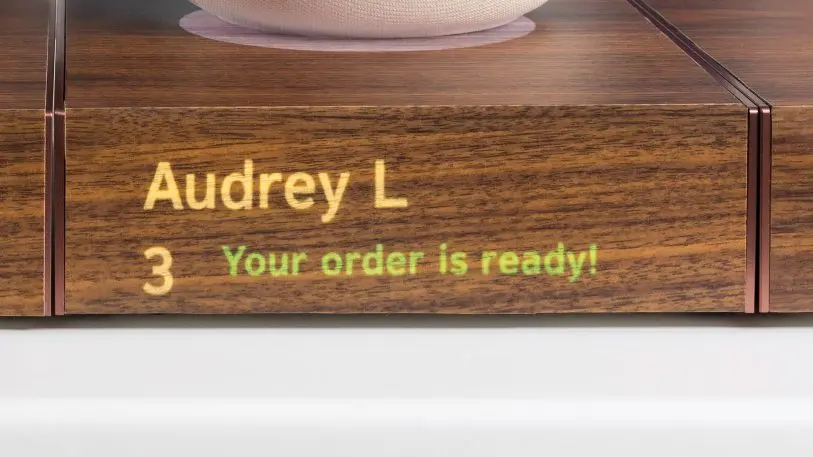

As orders are completed, the shelves light up in front with the customer’s name. (This name doesn’t pop up on a traditional LCD screen, but, rather, a proprietary display technology that creates a more subtle glow that is less distracting in a restaurant atmosphere.) The shelf senses when a bag of food has been placed on it or taken off, and can even alert the manager to an order that has sat there too long, and should maybe be remade.

“A lot of remote ordered food, operators are very worried about quality,” says Young. “Now, they have the ability to notice something has been sitting too long and do something about it.”

Spotlight’s cleverness, however, is not just its connectivity: It’s in its flexibility.

“Each Spot is an individual piece of hardware mounted and tethered together. That means the brand that doesn’t have a lot of space and doesn’t need many can take three. The brand that is doing much higher volume and embracing these delivery services can take 10,” says Young. “And because it’s a modular, very-small-footprint unit, it can be deployed in different ways.”

As Young explains, the average service counter has about four linear feet, which is perfect for storing five or six Spot units. But Spots can also be built into a stacked cubby system. Or they can be mounted on a wall as floating shelves. Or they can be built into a full bookcase shelving unit.

Spotlight is launching with three restaurants in San Francisco, Seattle, and Chicago in the coming weeks, and the technology is now open for any restaurant to license. There’s an upfront cost for the hardware, which runs “maybe a couple thousand” depending on the size of install, according to Young. Then there’s a smaller, ongoing licensing fee.

Eatsa’s platform may be too high tech or expensive for the tight margins of the independently owned restaurant industry (my favorite taqueria still only takes cash and has tables from 1970s), but it’s easy to imagine it scaling to fast-food or fast-casual chains with their copy-and-pasted business models.

“We’re having conversations up and down the spectrum and getting, honestly, a lot of traction across the board,” Young maintains, “because everyone is trying to solve this problem.”

If we’re really going to eat 10 times the delivery tomorrow that we do today, then restaurants may soon need to think about delivery first and dine-in second.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.