When Trader Joe’s customers complained about the fact that the store sold cucumbers individually wrapped in plastic—something that supermarkets do to reduce food waste—the retailer eventually started using plant-based compostable wrappers instead. In Switzerland, the supermarket chain Lidl is taking a different approach and helping produce last longer by adding an invisible, edible, plant-based coating.

It might seem like most fruits and vegetables don’t need protection at all; a plastic wrapping a banana, which comes with its own natural packaging, sounds like the ultimate absurdity. But unless we’re all eating local food shortly after it’s picked (which would mean no bananas for most Americans), packaging can actually have some benefit. Because so much energy goes into producing food, wasting that food may be responsible for as much as 10% of global emissions.

France just became the first country to ban plastic packaging on individually-wrapped cucumbers and 30 other types of fruits and vegetables. The law just went into effect, with a full phaseout for other produce by 2026. The government estimates that it will eliminate more than a billion pieces of plastic packaging a year.

“It’s certainly an important challenge to try to, as much as possible, reduce food waste, and plastic can do a good job at that, but we’re are concerned about plastic that is not properly recycled,” says Gustav Nyström, head of the cellulose and wood materials lab at Empa, which is collaborating with Lidl on the new solution. “Those materials are extremely stable. And that’s part of the problem that we’re seeing in the environment, both in the oceans and in the landfill, where these plastics and microplastics are piling up.”

To make the new coating, the researchers started with “pomace,” a mash left over when fruits and vegetables are blended for juice. The material would normally be waste. “We’ve developed a process where we can extract the cellulose that is naturally contained in these vegetables that can not otherwise be sold,” Nyström says. By coating or spraying the cellulose onto something like a cucumber or banana, it creates an extra layer of protection, so moisture doesn’t escape from the produce.

It’s similar to the approach taken by Apeel, a U.S.-based startup that makes invisible, edible coatings for produce, though Nyström says that Empa’s technology is simpler. It’s also likely to be less expensive, since it’s made from a very low-cost material, and just a small amount is required on each fruit or vegetable. Because the material comes from food waste, it’s also a circular solution.

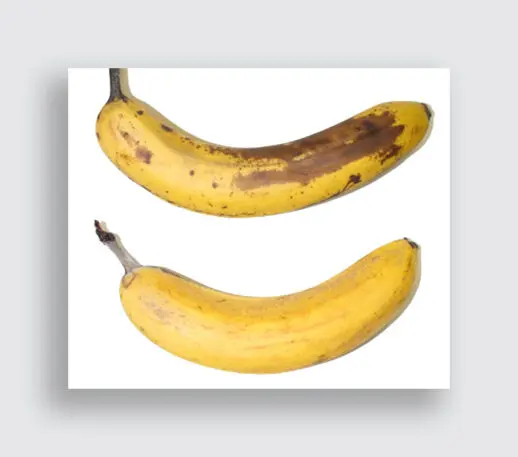

In lab tests, produce treated with the new coating lasted significantly longer. Bananas, for example, lasted more than a week longer than they would have otherwise. On fruits or vegetables with a peel that is eaten, the coating can be washed off, but it’s also safe to eat.

The researchers didn’t compare the solution directly to plastic wrapping, though they concede that plastic still probably protects fruit better. “The plastic is creating an almost perfect barrier, and it’s difficult to replicate with a natural, biodegradable or edible material like we have,” says Nyström. “So it’s not really a fair comparison.” Still, it’s a way to help reduce food waste while simultaneously cutting plastic waste. And as new laws on single-use plastic waste come into effect, retailers may not have a choice.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.