San Francisco’s Moscone West convention center has hosted its share of giant developer conferences over the years, from Apple’s WWDC to Google I/O to Microsoft Build. Adobe’s Tech Summit has a similar look and feel, with a splashy keynote, a profusion of demos all around the building, and lavish spreads of food for attendees. But this particular developer conference has one key difference: The developers in question are all Adobe employees.

Last February, at the 2019 edition of the biannual event, there were more than 3,000 of them on the premises—not just Bay Area locals but also staffers from faraway offices, including around a thousand from India alone. Many more participated in the event via live stream.

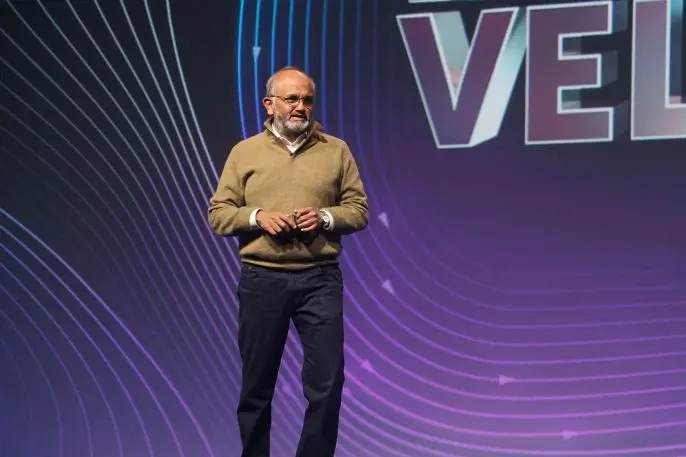

Back in 1998, Adobe’s current CEO, Shantanu Narayen, was a new Adobe recruit. During his first week on the job as senior VP of worldwide product research, he attended a Tech Summit. “Everybody fit in a small ballroom here at the [San Jose] Fairmont,” he remembers. Twenty-one years later, the event, though massively larger, attempts to preserve the intimacy of its early days. “Increasingly, it’s the collaboration between these people and the ideas that bring together magic,” says Narayen. “And so from our point of view, it’s one of the best investments you can make.”

Adobe shipped the first version of Illustrator more than 32 years ago, when a loaded Mac came with a 16-MHz processor, 4MB of RAM, and an 80MB hard disk. Photoshop is 29 years old. Premiere is 28, Acrobat is 26, and InDesign (which I still think of as a relative newcomer) is 20. Among major purveyors of software, only Microsoft offers as many products with decades-long bloodlines. Plenty of Adobe products are far newer, but even those that aren’t even out yet, such as the Fresco painting app for the iPad, live within the ecosystem defined by the company’s oldest and best-known products.

It’s today’s research that ensures that Adobe’s apps, regardless of their age, have a vibrant tomorrow. Once stand-alone pieces of software, the company’s creative tools are now delivered via Creative Cloud, a subscription service that (in its higher-end tiers) offers access to a smorgasbord of apps, with unlimited access to new versions and more frequent updates than in the era of the boxed upgrade.

And by the time a breakthrough becomes an everyday feature that Adobe’s customers take for granted, the company’s researchers have moved on in search of their next big thing. “When it becomes a commodity, it’s not any fun anymore,” says Miller.

Getting there faster

Not surprisingly, much of the research that is presently making its way into Adobe’s products involves machine learning and other flavors of artificial intelligence. According to Narayen, AI is not redefining Adobe’s mainstays so much as helping them achieve the aspirations they’ve had all along. As product teams work on these venerable, feature-laden programs, “they always had this miles-long list of the kinds of cool things that they were imagining,” he says. “I think the pace at which they can check off things on that list has improved.”

In Photoshop, for instance, selecting a particular item for editing has always been one of the most common tasks—and, if you wanted to do it precisely, one of the most tedious and painstaking. Adobe has long worked to make the job easier, and in recent years, machine learning has allowed it to do so in great big bounds rather than baby steps. A feature called Select Subject, introduced in January 2018, makes it a one-click process (as with a lot of AI, it’s amazing when it works, but doesn’t perform flawlessly all the time). Another technology known as Fast Mask—still a demo rather than a shipping feature at the moment—does similar things for video with a couple of clicks: “For a professional videographer, it takes days to do this kind of masking,” says Parasnis.

Adobe’s AI initiatives also differ from those of a Google, Amazon, or Microsoft in that their aspirations aren’t limitless. “We’re not trying to build a self-driving car,” says Scott Prevost, VP of engineering for cloud technology. “We’re not trying to cure cancer. We are laser-focused on the domains where Adobe has a deep history of expertise and knowledge.” Those domains—tools for creating and wrangling imagery, documents, and experiences—still provide a broad enough tapestry to encompass everything from Photoshop’s content-aware fill to Acrobat’s smart form-filler tools.

That said, Parasnis emphasizes that the goal is to concentrate on work that might lead to Adobe creating powerful features that large numbers of people will happily pay for, whether in an update to an existing app or an all-new one. “To be clear, we like to actually build profitable businesses, so it’s not like we’re just a research lab with no desire to succeed in the market,” he says. “But we do take a lot of pride in being a company that has to reinvent itself constantly.”

As a raw piece of technology, it’s easy to visualize this being useful in an array of Adobe products. But the experience would need to be different in each one, which is a reminder that a research breakthrough is only the first step in making a product more useful. That’s why Magic Layouts remain an unreleased demo while the company works to refine it. “We’ve been collaborating with our product team so that we get input on what kind of things they are interested in,” says Adobe Research senior principal scientist Hailin Jin. “How we can design the interface so that it works for designers. Our target is UX designers, and those people are different from Photoshop users or graphic designers, and so on.”

As AI starts to work its way into almost every nook and cranny of Adobe products, it’s no longer purely the purview of researchers, or even coders with a deep background in the technology. So two years ago, the company decided to create a nine-month course in AI for thousands of engineers who weren’t AI specialists. “What’s great is they come back and say, ‘Can we get five more new courses?'” says Parasnis.

Next-generation creativity

In the 1980s, Adobe’s founding product, the PostScript page definition language, was the result of founders Warnock and Geschke’s research. It became a hit because it let laser printers crank out crisp black-and-white typography at 300 dpi. Since then, everyday communications have grown ever richer, and the toolset Adobe provides has expanded to encompass color, video, animation, sound, and a whole lot more.

Now PCs and even phones and tablets are being joined by new types of devices, from AR and VR headsets to smart speakers, that interact with the world in ways that old-school devices did not. “Computers are going to go from just number crunching and communication to devices that can have human-like sensibility,” says Parasnis. “Where they can hear us, they can sense us, they actually can sense the world around us.” This epoch-shifting change requires Adobe researchers to contemplate not just new features, but entirely new kinds of products.

Adobe being Adobe, those products will be aimed at helping people create and manage content. Augmented reality, for instance, has been slowly gaining steam ever since Pokémon Go launched in 2016. But “what people don’t realize is creating those applications is incredibly hard,” says Narayen. “And we’ve always been about democratization. Think about photography before Photoshop: It was the domain of a very small set of people, and now billions of people have access to it. And we’ve played our role in that.”

Adobe’s gambit to democratize AR content creation is still a rough draft, as reflected by the fact that its current name—Project Aero—is a placeholder. Aero doesn’t exactly aspire to do for AR what Photoshop did for photos. Instead, it’s based on the philosophy that creatives who are comfortable in Adobe tools such as Photoshop and the Dimension 3D modeler should be able to use the tools they already know to create AR content. Aero will allow them to layer that content into real-world scenes, taking advantage of the cameras and sensors on hardware such as iPads to enable functionality that wouldn’t be possible on an old-school desktop computer.

Though Project Aero remains a work in progress, it’s a critical undertaking for Adobe. After all, if Adobe doesn’t establish itself as the Adobe of AR authoring, someone else will.

“It’s a little bit like the Innovator’s Dilemma,” says Silka Miesnieks, Adobe’s head of design for emerging tech, of the company’s forays into new areas. “We’re trying to eat ourselves, right? Eat the products that we’ve had, and then invent and create new markets, stretch ourselves further, stretch our products further.”

Then there are the company’s more speculative efforts, such as Project Glasswing, which Adobe demoed at the SIGGRAPH Computer graphics conference in July. It’s a display technology that permits text and graphics—such as those you might create in Photoshop—to appear on a transparent touchscreen in front of real-world objects, creating a mixture of the digital and physical that Adobe thinks could be useful for purposes such as retail and exhibits.

The fact that Glasswing involves hardware built by Adobe researchers is not a sign that Adobe wants to get into the display business. The company doesn’t know where this experiment might lead, and that’s okay. It might even be the whole point.

“If you can connect all the dots between where you are today and where you think things are going, you’re probably not being aspirational enough,” says Narayen. “With researchers, you have to sort of plant this flag of, ‘Why can’t we do this?’ And they go off, and then they amaze you with their ingenuity.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.