In 2014, Stanford student structural engineer Ahmad Wani was visiting family in his native Kashmir when a catastrophic flood struck. The rising waters stranded him and his family for seven days without food or water, during which they watched their neighbor’s home collapse, killing everyone inside.

After this horrifying experience, Wani was struck by just how disorganized the emergency response was. “There is no science behind how people should be rescued,” he says. “Disaster response is really random.”

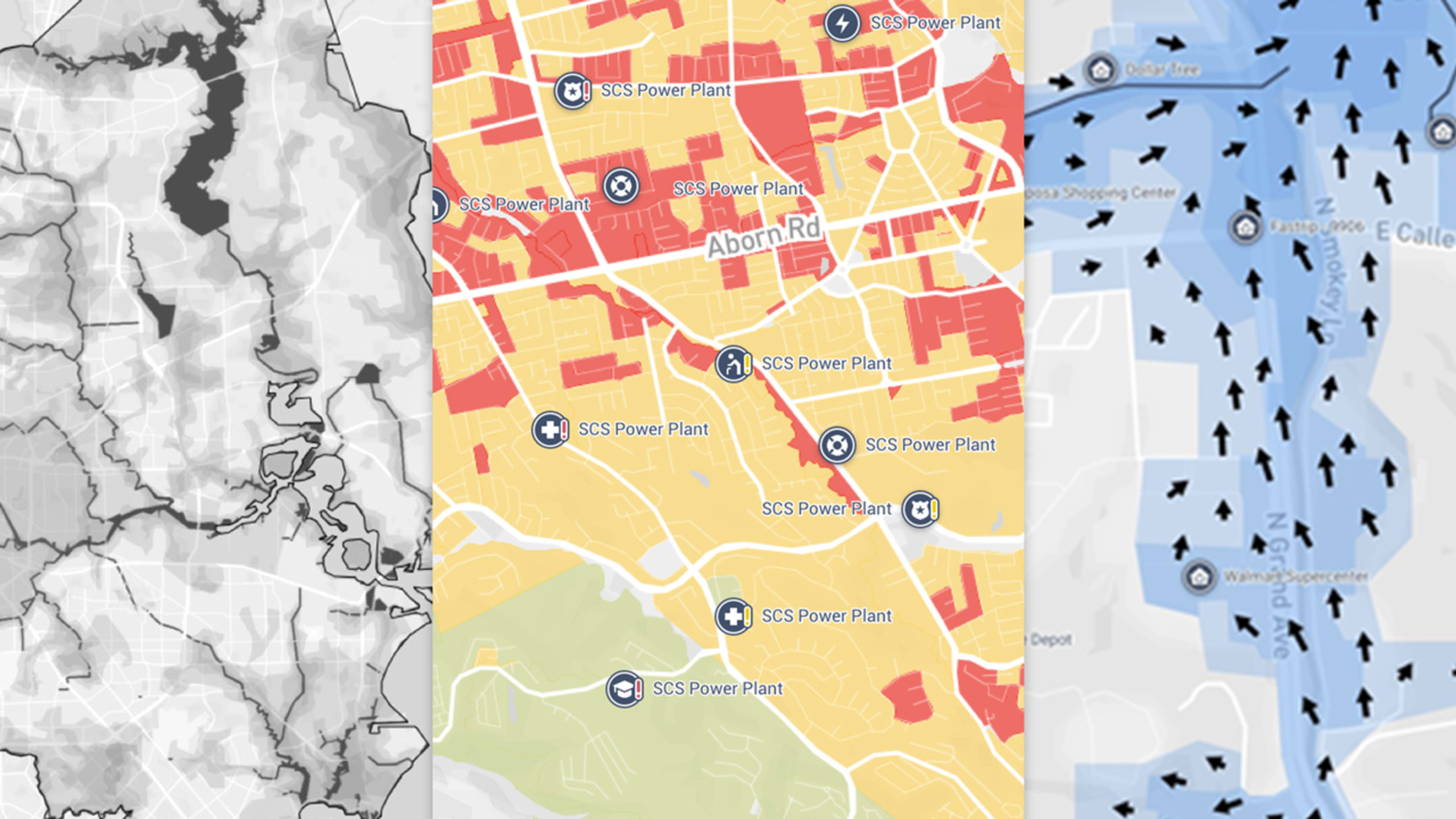

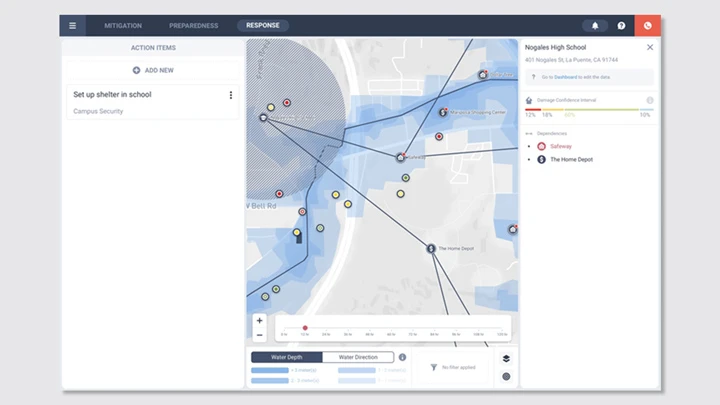

Today, Wani’s startup One Concern is launching a machine learning platform that provides cities with specialized maps to help emergency crews decide where to focus their efforts in a flood. The maps update in real-time based on data about where water is flowing to estimate where people need help the most. It’s the latest in a wave of AI-powered tools aimed at helping cities prepare for an era of severe, and increasingly frequent, disasters.

Since 1980, the U.S. has suffered from 219 climate disasters that cost over $1 billion, with the total cost exceeding $1.5 trillion. In 2017 alone, these disasters cost the country $306 billion. Since 2000, more than 1 million people have perished from these extreme weather events. As climate change heralds more devastating natural disasters, cities will need to rethink how they plan for and respond to disasters. Artificial intelligence, such as the platform One Concern has developed, offers a tantalizing solution. But it’s new and largely untested. And the urgency is growing by the day.

From earthquakes to floods

After surviving the devastating flood in Kashmir, Wani returned to Stanford, where he was studying structural engineering. He began contemplating how to predict a disaster’s damage. The idea was that if city officials could anticipate which areas would be most harmed, they would be able to deploy resources faster and more efficiently throughout the disaster zone. But he had a problem: analyzing a single building using traditional structural engineering software took seven days on Stanford’s supercomputer. “We had to recreate that for the entire city” for the idea to work, Wani says. “We didn’t have seven days or seven years. We wanted to do it in three to five minutes.”

He decided to focus first on earthquakes, which are more of a threat than floods in California. Wani teamed up with fellow Stanford students Nicole Hu, a computer scientist who focuses on machine learning, and Tim Frank, an earthquake engineer, to build an algorithm that can digest data about how a building was built and how it’s been retrofitted over time. This data is combined with information on the building’s materials and surrounding soil properties to extrapolate what happens to this system when shaking occurs. Then, when a quake hits, the model absorbs new information coming from on-the-ground emergency responders, 911 calls, or even Twitter to make its predictions of the damage more accurate.

Because the model identifies patterns by looking through large amounts of data, it needs less computing power than the previous method of asking a computer to perform complex physics equations to understand how shaking will impact a structure. The trade-off is accuracy: Hu estimates that the algorithm is only about 85% accurate. With more data over time, that number will improve, but the team believes that it’s good enough to paint a broad picture of damage immediately after a quake. (Of course, they won’t know for sure until a major earthquake hits.)

Wani, Hu, and Frank started One Concern in 2015 and then released its earthquake platform, called Seismic Concern, in 2016. Seismic Concern predicts the damage caused by earthquakes on a block-by-block level and is now used by eight different municipalities, including the cities of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Cupertino.

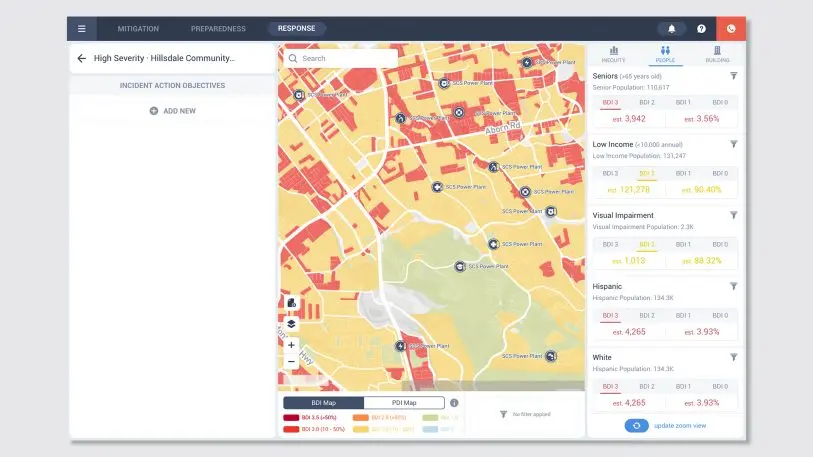

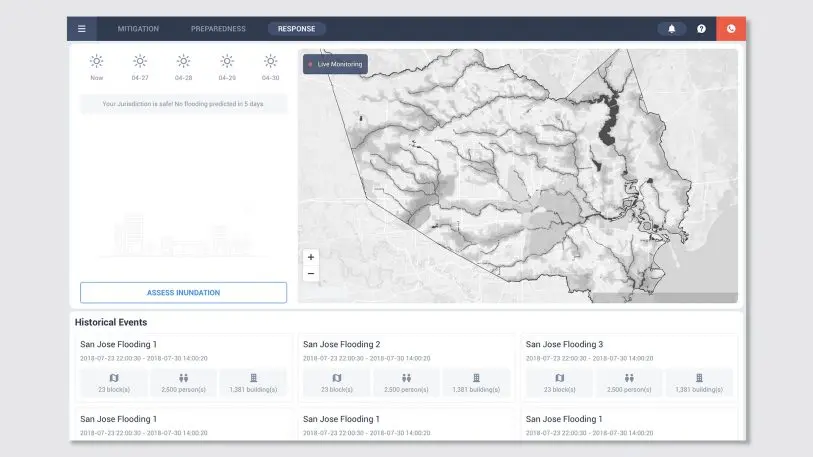

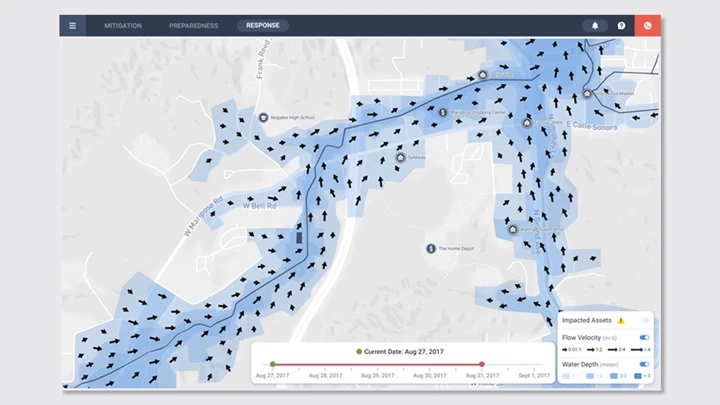

Now, the company is launching Flood Concern, a constantly evolving risk map that crunches huge amounts of data based on the physics of how water flows, information about previous floods, and even satellite imagery to approximate the depth, direction, and speed of the water–and determine which areas of a city are most at risk. Layered on top of the damage prediction is demographic data, so that emergency planners can see what areas of a city might have particularly vulnerable populations, like a significant percentage of seniors or disabled citizens. With that kind of information, planners can figure out which areas should be evacuated, where to put shelters, and what critical infrastructure–like schools or hospitals–needs the most help when flooding begins.

The sad state of emergency response

Emergency planners have little technology to work with when it comes to understanding what is happening during a disaster. For floods, many emergency planners rely on static risk maps, which model the flow of water by assuming that rain is falling constantly everywhere. These maps are based on the probability that a flood will happen in any given year: A 100-year risk map has a 1% risk of happening, while a 500-year risk map has a .2% annual probability. These models never change, even as dams burst and flood water reshapes entire neighborhoods. Emergency response teams often react based on what 911 calls come in, with little data to help prioritize resources on a city-wide level.

But this process is outdated. “We’ve had four of what they call 500-year events in 20 years,” says Tom Bacon, the chairman of the Houston Parks board who is not affiliated with One Concern but has thoroughly examined the software. “Each time we’re reinventing the process for recovery, reinventing the process for solutions going forward, and we’re not using either historical information or maintaining an accurate record of the current conditions in order to make the best decisions about how we invest. That’s simply because the ability of static databases to understand these fast-changing cities is so limited.”

It’s a similar story when it comes to earthquakes. According to Mike Dayton, the deputy director of San Francisco’s Department of Emergency Management, state-of-the-art technology during an earthquake is a shake map, which shows the magnitude and epicenter but contains no detail about the extent of damage. Dan Ghiorso, fire chief of the California city of Woodside, told Fast Company earlier this year that he has relied on an even lower-tech strategy: responding to 911 calls and just driving around his district to see what kind of damage resulted from an earthquake.

Other companies are trying to tackle these problem using AI. Like One Concern, Geospiza uses data to create city-specific action plans for a variety of disasters using a map-based interface. The nonprofit Field Innovation Team is using machine learning to predict what people in shelters will need post-disaster. Microsoft is getting into the game too, with a recent announcement that it will be investing in AI tech related to disaster response. But One Concern has heavy hitters in the emergency management industry on board, including Craig Fugate, former head of FEMA under Obama, and Greg Brunelle, who headed up New York State’s emergency management agency. The company also focuses on releasing separate tools for each type of disaster rather than a blanket AI that can handle all of them.

Seismic Concern can start generating predictions 15 minutes after an earthquake hits with about 85% accuracy, and constantly updates as on-the-ground data about the actual state of damage comes in from 911 calls and emergency response teams. There’s also a mode that allows cities to look at more conservative predictions: If a city has more resources than they know what to do with, the mode will help them figure out where to deploy those resources to be extra safe.

Even though there hasn’t been a big quake since San Francisco started using Seismic Concern, Dayton uses it for other types of emergencies as well. Earlier this year, when a high-pressure gas line ruptured during construction, Dayton used Seismic Concern’s demographic layer to look up the types of residents in the area the city planned to evacuate. He said it helped the city decide if they needed a shelter and how big it should be. “It’s not just something that we’ll trigger after the major earthquake,” he says. “It’s a tool we’re using every time we have a shelter or evacuation order.” The city has been using the platform for about two and a half years and has a multiyear contract with the startup at a rate of $100,000 a year.

Mitigating disaster when climate change comes knocking

Organizing emergency teams in the immediate aftermath of a disaster is crucial. But so is long-term emergency planning, especially since disasters will become more severe and more frequent in many parts of the United States. One Concern has a mode where officials can run thousands of simulations to understand their city’s weaknesses so they can retrofit buildings and plan how to distribute resources before disaster strikes. “They get an understanding of how does this building or this resource look as compared to this other building or other resource on an annualized aggregated damage level for all the possible scenarios of earthquakes,” Wani says.

It’s almost like playing SimCity, where planners click on a fault, watch what happens to each building, and then add icons like sandbags, shelters, or fire trucks to see how these preparation tactics influence the simulation. All of this happens within a relatively simple color-coded map interface, where users toggle on different layers like demographics and critical infrastructure to understand what the damage means in more depth. For emergency planners and responders on the front lines, One Concern’s easily understandable UX can help make the chaos of disaster a little clearer. Dayton says the simulations have helped San Francisco validate where it has decided to put shelters in case of a quake. In Woodside, Ghiorso says its helped the emergency planners identify which buildings need to be retrofitted to survive shaking.

“Cities need to figure out what’s the best use of every public dollar that they’re spending,” Wani says. “Should they upgrade the city hall, the bridge, this road, or should they buy a firetruck? What makes the most sense in terms of saving the most lives or livelihoods?”

Bacon of the Houston Parks board believes that cities need to bring more data into planning for the future. “We probably need $25 billion of investment for the next level of resilience and sustainability for these events. We’ll probably get $10 billion [from the government],” he says. “This platform I believe can make us do better models and make better judgements on how we best apply that $10 billion to create safety and sustainability for the greatest portion of the population and have the least amount of impact and future reinvestment required when this happens again.”

But to make all this happen, One Concern and other AI startups working on these problems need good data–and lots of it. That kind of data isn’t always available, especially in developing countries. Hu and her team are currently conducting a pilot study in Bogota, Colombia, where they are testing to see whether they can use a smaller data set to make more widespread predictions for the rest of the city. The team found that they were able to do so in San Francisco, but cities in other countries don’t always have enough data to make predictions accurate enough.

And even when an algorithm does have enough data to be reasonably accurate, there’s a bigger question: Should we rely on algorithms to decide where to send resources, and where to invest in our cities? Given the harmful lack of nuance that algorithms have demonstrated in other aspects of our lives–like on social media–could a computer program really adequately parse problems as complex as disaster relief?

It’s a thorny question with no easy answers. But cities are running out of options. Emergency responders are keen to explore any tools available to diminish the impact of disasters, like the huge wildfires that are overwhelming the state of California right now. Next on the One Concern’s agenda is Fire Concern–which is particularly pressing given Hu says that in some places, the occurrence of a fire can exacerbate a flood because it changes the topography of the land, resulting in the water flowing at a much higher speed. As One Concern continues to build its models and add more data to them, the results will only get more and more accurate.

When it comes to fires, Ghiorso of Woodside is hoping that One Concern will be able to tell him how much the weather is impacting the chances of a fire so that he can prepare more effectively. “Climate change has changed the game,” he says. “We have to find a better way of doing this. We need to figure how to mitigate it.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.