Gil Shklarski has spent his career solving incredibly complex problems. Whether it was making Facebook safer or working on infrastructure for Microsoft’s maps, he’s always approached his work with a mathematician’s ability to break enormous missions into problem sets to be solved. Five years ago, he joined Flatiron Health as head of technology, and was tasked with building the oncology industry’s first cloud-based software platform to manage clinical care and learn from the experience of every patient. Sounds like a big enough challenge–but scaling the technical team to do it quickly proved to be a massive undertaking on its own.

When Shklarski came aboard, the company was four employees building tech used by one clinic. Two years later, headcount was 135, serving 200 clinics, and he confronted a problem with the potential to undermine it all. It wasn’t a technical problem, or a medical one. It was a people problem: his engineering leaders had a hard time making streamlined decisions, whether it was negotiating with product leaders or creating alignment around an internal debate.

Related: This CEO Doodled A Handy Chart For Balancing Growth With Profit

It wasn’t immediately clear how he’d turn things around. But Shklarski, now CTO, had been using a framework, introduced to him by his executive coach Marcy Swenson, that had helped him navigate his own hairy decisions. He realized how helpful that same tool would be if it were applied team-wide. In this exclusive piece–based on a talk he gave at First Round’s CTO Unconference–Shklarski walks through the matrix he adapted to enable his increasingly autonomous and fragmented team to keep moving fast and smart through tough choices.

“Xanax For Decision-Making”

This is the nickname Shklarski’s framework has earned for itself at Flatiron. But before it became useful, they had to identify the exact nature of the problem and anxiety they were experiencing.

“As you scale, one team turns into many, and each one needs to run on its own and feel good about making decisions locally without parental supervision,” he says. If a company fails to do this, its progress will languish and its culture will erode. “Teams that can’t commit are a drag on leadership’s capacity, preventing them from working on strategic problems by keeping them busy with local ones. This will impact growth, deflate morale, cause attrition.”

Even if this isn’t happening quite yet, it’s a fork in the road every growing company will one day arrive at–hopefully prepared for what’s next. In this context, being prepared means making everyone on board feel empowered to make smart, strong decisions for the company. It’s a rare startup that actually anticipates and manages this transition in advance.

Related: The One-Page Cheat Sheet To Your Most Productive 90 Days Ever

Shklarski realized it was happening at Flatiron when the role of technical lead started to become unattractive. People were uncomfortable facilitating decision making; they didn’t want to negotiate with their colleagues. Instead of stepping in to resolve individual issues as CTO, he decided to solve for his team’s reluctance to make quick decisions in the first place.

When a team expands quickly, a bunch of new, rookie managers typically get anointed to handle a continuous stream of problems. Some of the problems are new, some are old. Many get revisited, because serving five customers is radically different than serving 100. For managers, it can feel like there’s no time to consult others or incorporate feedback. They either end up making a bunch of judgment calls themselves or relying on slow, uneasy team consensus. At Flatiron, this resulted in a lot of crippling, culture-threatening stress.

“Eventually, we asked our Learning and Development team to interview our engineering leads about what was causing them stress,” Shklarski says. “It always came back to the difficulty around making decisions. There was little alignment among the different voices on each team, and a lack of strong leadership to help negotiate a path forward.”

Shklarski saw the framework from his coach as a tool for his team leads to quickly and efficiently create alignment around decision-making–and at the same time, foster a level of psychological safety that would take fear, self-consciousness, and anxiety out of the process.

“Applying it to my own decisions helped me see things from others’ perspectives, removed my biases about how other people would judge my actions, and helped me stay motivated by what was right rather than what others or my boss would think,” he says. “I wanted leaders on my team have this tool at their disposal.”

Related: This 100-Year-Old To-Do List Hack Still Works Like A Charm

The Matrix

It’s important to understand the distinction between good decision-making and good decisions. You can make a good decision that will still create chaos throughout your team if people aren’t happy with how it was made. This framework is about improving team alignment while reducing stress in the decision-making process.

There are two types of decisions:

- Irreversible decisions

- Reversible decisions

This system can be used for either. But Shklarski’s goal was to optimize for Type 2 decisions. Those come up the most often, and are exactly the sort of thing that shouldn’t be escalated to top leadership. “People will expect and accept scrutiny and overhead for Type 1 decisions,” he says. “Streamlining Type 2 decisions makes teams and the people on them happy, allowing things to be accomplished without the usual stress.”

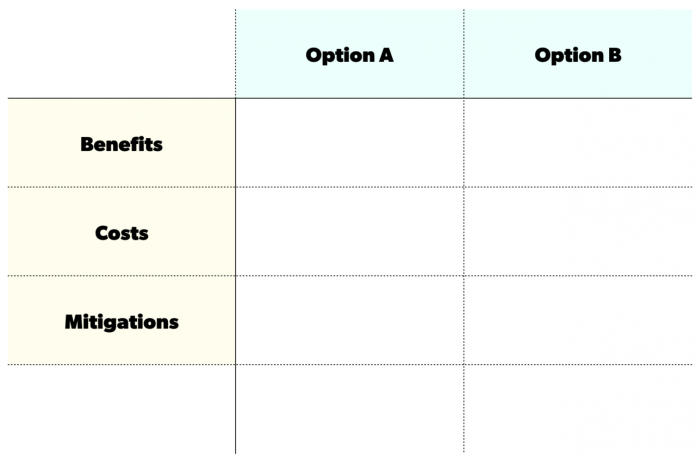

It starts with a basic chart, with the two (or more) options you’re deciding between at the top. Down the left-hand column, you have benefits, costs, and–uniquely–mitigations.

Related: One Googler’s Insider Guide To Using Google Docs At Work

This chart might look like a generic pro/con list, but the real magic happens when you put it to work. In particular, it lives in the row labeled ‘Mitigations.’

“The leader of the exercise should really be more of a facilitator, rather than placing their own opinions and judgments at the forefront,” Shklarski says. “She should encourage everyone to ideate and include the social considerations or ramifications of each option–not just the cut and dry causes and effects on the work. For example–will a boss be made happy by a certain decision? Will a team be energized? Will someone who deserves visibility in the organization be given an opportunity?”

The facilitator also needs to ensure no one is dominating the conversations and everyone gets to document their perceived benefits and concerns. This contributes to psychological safety by fostering conversational turn-taking. Filling in the Cost and Benefit slots for each choice should be pretty straightforward. Notably, the Cost row should also emphasize the risks associated with each choice.

The only other thing to watch out for is making sure you’re generating enough in each column, and thinking holistically around exactly how selecting a particular path will play out in reality. Who will be helped? Who will be upset? What are the long-term impacts? The short-term impacts? As the company grows, how will these impacts change? Really dig in and project each choice into the future.

Then you get to Mitigations. “This is where the facilitator should walk the group through how to soften, allay, or distribute the risks associated with each of the options,” Shklarski says. “If you didn’t do it already, this exercise forces you and everyone to think through what it would really be like if that option were selected.”

Having mitigation conversations elicits opinions and feedback from a wider range of people, and prompts the group to see the situation from other points of view–including those of other departments within the company that might touch or be affected by the decision at hand. It also gets everyone collaborating on possible solutions to the negative impacts on others. Here are some best practices for mitigating risks and generating this row of the matrix.

Ask yourself questions that add an objective shifted perspective:

- What would be best for our customers?

- What would be best for the patients? (Or people who are ultimately impacted.)

- What would the board want us to do? (The board represents objective good for the company.)

Ask yourself questions about addressing the risk from a different angle:

- What is the root cause of that cost/risk, can we mitigate it?

- Can we address this tech-debt/management-debt in other ways?

- Can we resolve the underlying anxiety through other means?

- Is there a long-term/short-term tradeoff we can make?

The exercise allows everyone on the team to put their fears, hopes and social anxieties into the decision-making process, and see them taken seriously as important factors. Sometimes through the conversation you end up adding a Column C or D because new options or ideas emerge with different or fewer risks.

The Matrix In Practice

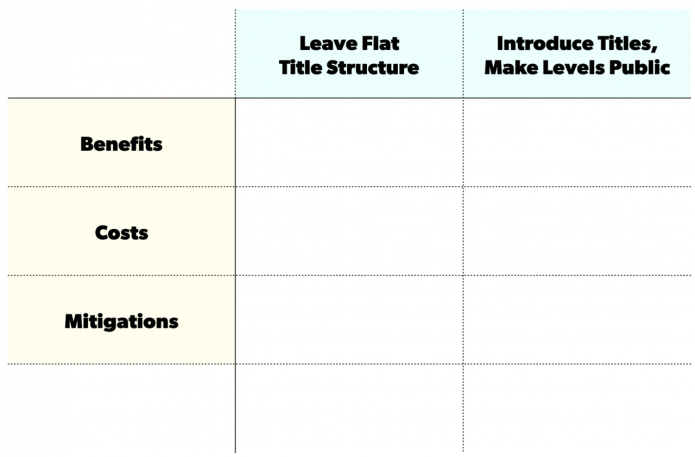

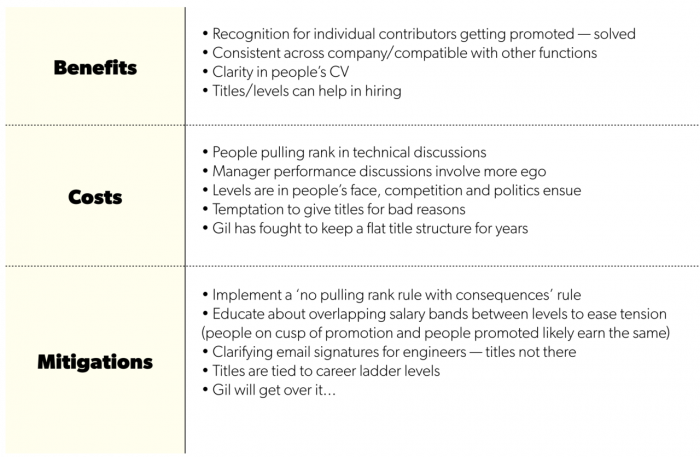

Last year, Shklarski applied this framework to help Flatiron’s engineering team make a contentious decision. Should they have more descriptive job titles signifying seniority or not? In this case, the matrix helped defuse what could have been a very heated situation, and made everyone empathize with the tradeoff and feel more comfortable with the outcome. Here’s a detailed breakdown of how it worked.

One of the engineers pointed out that the sales team had more descriptive titles (manager, director, senior manager, etc.) while the engineering team did not (everyone’s title was engineer). Others agreed. Factions lobbied for either side. This is exactly the type of decision that could have been a deadlock in the past.

Shklarski invited his top engineering leaders and technical HR lead to meet and align on the decision, presenting the following chart on Google Docs:

- He asked the group to fill in the benefits and costs of each decision, and to take a pass at what might be done to mitigate the related costs.

- This exercise helped those involved see the tradeoffs and imagine what each scenario would look like after the decision was made.

- People’s emotions and social ramifications were emphasized.

- Reconvening as a group, they discussed ideas for addressing the negatives of either plan. A decision was reached collaboratively, instead of being handed down, based on what would produce a positive net impact for the greatest number of people.

“When I make decisions this way, I always say, ‘Okay, this is where we ended up. Here is your ’24 hour freakout window, during which we can revisit the decision,'” Shklarski says. “Unless someone says something different in the next 24 hours, we’ll go with it.”

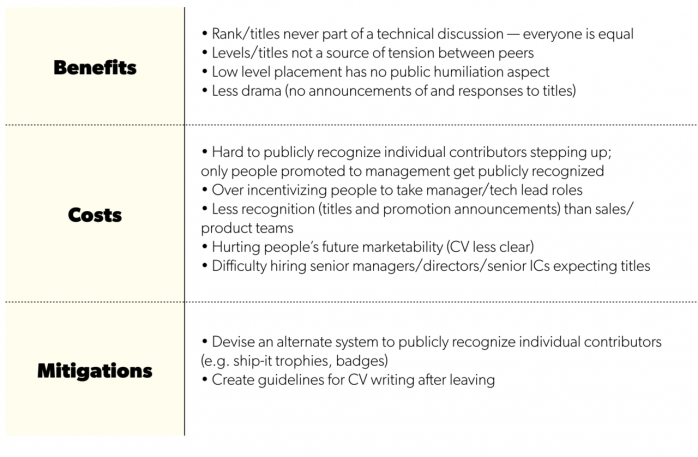

Here’s how the matrix looked at the end of the exercise:

A: Leave flat title structure

“No one complained about the ultimate decision in this case,” say Shklarski. “And the empathy that the exercise generated is evident in that result.”

As he points out, the charts generated during decision-making meetings can and should be stored to refer to later–by new employees understanding the evolution of things, by teams revisiting old decisions, by people proposing something new after some time has gone by, etc.

But ultimately, the mitigations row is the secret sauce. It provides a place for all opinions to be documented. It serves as a forcing function for people to hear, understand, and empathize with others’ points of view and proposed tradeoffs. And it makes the task of aligning everyone an organic process. Today, Flatiron has 450 employees and its tools are integrated into 265 clinic across the country. The volume and velocity of decisions are as intense as ever, but the culture around those decisions is much healthier–largely because the matrix has become the default for creating alignment while making everyone feel heard.

It’s been applied now so many times–in situations beyond Shklarski’s initial imagination–that it’s become a cornerstone of Flatiron’s engineering culture: One small chart, useful no matter how big the company gets.

A version of this article originally appeared on First Round Review. It is adapted with permission.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.