In the excerpt from their new book, Founder vs Investor: The Honest Truth About Venture Capital from Startup to IPO, Elizabeth Zalman and Jerry Neumann explain how the relationship between those running the startup (the founders) and those investing in the startup (the investors) is destined for conflict.

The genesis for the book came from a blog post Neumann wrote in November 2021 titled “Your Board of Directors is Probably Going to Fire You.” It shot to the top of Hacker News. Founders raved about it because a VC was finally talking publicly about something that was only whispered about. Investors were incensed that it was being talked about at all. Zalman called Neumann and asked, “Why don’t more people talk about things like this?” And so the book was born.

There was one caveat, though: Neumann insisted on fully representing the venture capital viewpoint, no half-truths, no compromises. Zalman agreed and became “the founder.” Their conversation manifests in a give-and-take, with the coauthors arguing their sides as they discuss the life cycle of a startup—fundraising, terms, the board of directors, growth, and exits.

Drawn from the book’s “Growth” chapter, the excerpt offers the coauthors’ dueling views on the often destructive friction that can happen when a startup begins to scale.

Investor’s view: The optimist’s dilemma

Jerry: Two years after I first invested in Liz’s second company, she went out to raise a new round. Several large VCs wanted to invest and they had bid up the price. The term sheet she was favoring valued the company at $300 million (these numbers are the right order of magnitude but are not the actual numbers; she’s still under NDA, so she’d just have to edit them out anyway). I had an unusual worry: The deal was too good.

She gathered her co-founders and we borrowed a friend’s office. I asked, “What does your company have to do over the next few years for this to be a good investment?”

- The VC wants to at least triple their money in five years, the earliest you could reasonably expect to exit.

- For the company to be worth more than $1 billion in five years, it will have to have at least $200 million in revenue.

Then I wrote six columns on the whiteboard, one for each year. I worked backward to a triple-double for the revenue. (The numbers here are millions of dollars.)

I added rows for different types of employees: sales and marketing, software development, customer support, and so on. How many of each would they need to support that revenue each year? When we did this exercise, Liz and one of her co-founders were the only sales and customer support people. But if the revenue tripled, that would no longer work. We worked out how many people they needed to hire, plus the lead time it would take to find them, get them on board, and train them. Liz quickly realized that (a) hiring would be her primary job for the next five years, and (b) they were already six months behind.

This is the dilemma of every successful startup. Customers love the product, so founders get excited. Founders go to VCs to get money to grow into customer demand, and want a very high valuation. VCs calculate they can offer the high valuation if the company can grow very, very quickly. The startup gets the money. But they also get the expectation—the mandate, really—of high growth.

Founder view: Product market fit means more problems

Liz: You’ve found product market fit and it’s time to scale. Congratulations! Most don’t. Now forget all that and stop patting yourself on the back, because guess what? It’s time to learn a whole new set of skills. And if you thought getting to product market fit was hard and that you’ve figured out the difference between life and death, you ain’t seen nothing yet. Why? Because now you have something that people will pay at least one dollar for, and on a consistent basis. This means you are no longer a call option for your investors.

(If you don’t understand what I mean, let me burst your bubble about Pre-Seed, Seed, and even Series A these days. To raise that money, you convinced people that you were smart or dogged or myopic enough to figure out how to take your idea and get people to buy it. Your investors’ job is to sprinkle enough money around across enough companies such that if any of them make it to the stage you’re at, they’ll exercise those ever-so-valuable pro rata rights and call that option. They’ve gone from investing $2 or $3 million to $10 or $20 million and you’re now no longer 1% of the fund; you’re 10%. Call option over. Real life has begun.)

How does it manifest? Biweekly calls. Board meetings actually being called. Questions about burn and hiring and offices and retained searches and COGS and revenue and churn and customer acquisition and competition. There are a million questions that you don’t have the answers to and nowhere near the expertise to even start thinking about how to attack. Your investors demand to know how you’re going to turn their money into a massive company. You really just don’t know. Even worse, you’re not even sure how to get there. What got you from 0 to 1 isn’t going to get you from 1 to 2. Your investors will be a broken record, asking the same questions over and over again. They’ll offer up the same half-dozen introductions they always have—that temp CFO that comes highly recommended but pawns you off onto associates, that sales prospecting “expert” they have as an advisor to the firm who spouts jargon so well he was probably born that way, the former CEO of Insert Large Public Company Here that knew what it was like to operate twenty years ago but with limited relevance for today’s enterprise SaaS startup, the executive coach that everyone uses who charges $1,000 an hour and sounds like she’s reading a self-help book—all while ignoring the real question: How on earth do I help this founder child (because face it, we are) grow into a CEO when I myself am not one? That last part your investor will of course ignore.

And that, my friend, is the crux of going up and to the right. VCs will expect you to figure it out with their expert help and introductions, all the while willfully ignorant of the fact that these rent-a-humans are generally useless. They’ll get frustrated when you mess up again and again and again, when things take twenty-four months when they “should” take twelve, that the market is “getting away from you,” disregarding the fact that you don’t actually have the majority of the tools you need in order to crush it. You’ll argue about the symptoms of the problem. You will maybe be able to articulate the real problem; your investors definitely will not.

The problem is that you as founder are now much less useful. The company now needs you to be an operator. And not just any operator, but the operator, the one who can triple revenue for each of the next two years. And you don’t know how to be that kind of operator. It’s possible you ran a small team at your last company. It’s possible you were a product manager. It’s even possible you were CEO of another startup previously (I certainly was). But guess what? You don’t know how to hire (well), to fire quickly (enough), to recruit, to run a management team (and especially one that gels), to manage the politics that can’t not be present in the company (no matter how well the line “we don’t have time for BS” in an interview lands, you do; it’s there), and we still haven’t touched on working with your investors, which means you also have to be a master politician.

In addition, your interests now start to diverge from that of your investors. If you are like most founders, you believe that you have a shot to sell early. The company is making real money and on an upward trajectory, which means that you’re morphing from a pesky gnat to an actual thorn in the side of the behemoth you’re trying to unseat. For your investor, you’re now one step closer to being a real opportunity to pay back the fund and one that’s now too big to ignore.

Investor view: Stages of growth

Jerry: As an investor, it’s exciting when you see a company break through into product-market fit. It’s like you’ve been driving around suburban streets and finally find the on-ramp to an open freeway.

But growth is hard. It’s hard to get going, and once it’s going, it’s hard to manage. Founders might want to throttle it back, while investors are insisting that they can go even faster. Growth is what the founder signed up for, whether they realize it or not.

Paul Graham, the founder of Y Combinator, wrote an influential essay called “Startups = Growth.” He says a “startup”—the kind of company venture capitalists like to fund—is different from all other companies that are started (hair salons, restaurants, dry cleaners, and so on)—because startups have to grow. If a startup wants to become a big, world-changing company in a short amount of time, then the most important thing they have to do is find a way to grow. Everything else follows from this: solving some customer’s problem really well, having a quality product, a great team, a potentially big market, and so on. All these things enable a startup’s rapid growth. The startup is irrelevant without the growth.

When they’re raising money, some founders make overly rosy projections to get VCs interested They pitch to dozens of investors, and the ones that believe the predictions make the highest offers, because they have the highest expectations. The founder accepts the highest offer, implicitly endorsing these high expectations.

At some point, the founder might say, “We need to take a break from growth for a little while to fix some things.” The VC’s immediate suspicion is that the company has hit the limits of their growth, they vastly overpaid for the company, and they have to either get tough on the founder or cut their losses.

The VC’s suspicions aren’t really irrational. If you’re at a slot machine that’s somehow paying out pull after pull and you decide to step away for a moment to “fix some things,” someone else is going to sit right down at that machine. Similarly, if you have a product that you have finally convinced customers they need and then you slow down selling it to them, someone else will step into your place. Before you existed, they didn’t know about your better solution. Now they do. And so do your competitors.

Every sale you don’t make is a sale someone else makes. Every day you stave off growth, that’s growth someone else takes. And each time, the VC sees your market share and corresponding value, and their ultimate payday, get smaller and smaller.

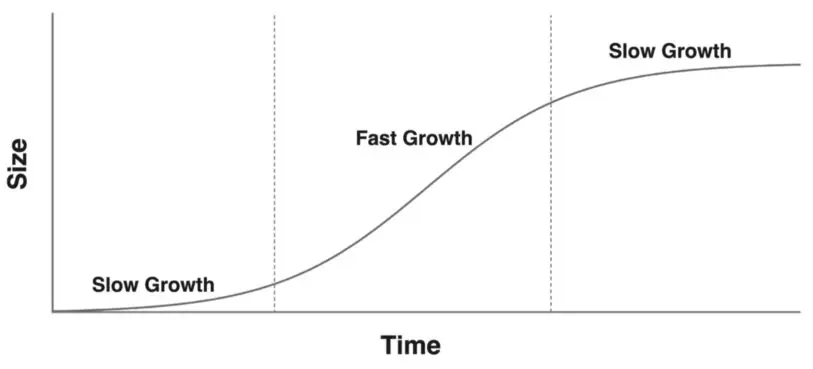

Graham says there are three stages to a startup’s growth:

- The initial period of slow or no growth while the startup tries to figure out what it’s doing.

- A period of rapid growth as the startup begins to figure out how to make something lots of people want and how to reach those people.

- Eventually, a period of slowing growth, as the successful startup grows into a big company.

This is the iconic S curve that pops up sooner or later in every book about innovation.

If a startup is in the first stage, the product isn’t quite right for the market yet, and the entrepreneur won’t be able to gin up real growth no matter what they do. But if the startup is in the second stage, where customers actually want the product, the only things blocking growth are standard operational problems: getting the product in front of potential customers, showing them it is what they need, signing them on as customers, and servicing them once they are. If the startup is in stage two, making sure these things get done is the founder’s only job. And if they’re not getting done, it is no one but the founder’s fault.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.