As car companies gear up for a future filled with electric vehicles, the workers who make those cars say they’re being left out. It’s become a big point of contention as the United Auto Workers union hashes out a new contract with Detroit car manufacturers.

The current contract between auto workers and the “Big Three”—General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis (formerly Chrysler)—expires on September 14. The UAW asked its members to take a strike authorization vote. On Friday, UAW said that though results are still being tallied, 97% of its members have voted in favor of strike authorization. That doesn’t guarantee a strike, but means 150,000 auto workers could take to the picket lines if a new deal can’t be reached in time.

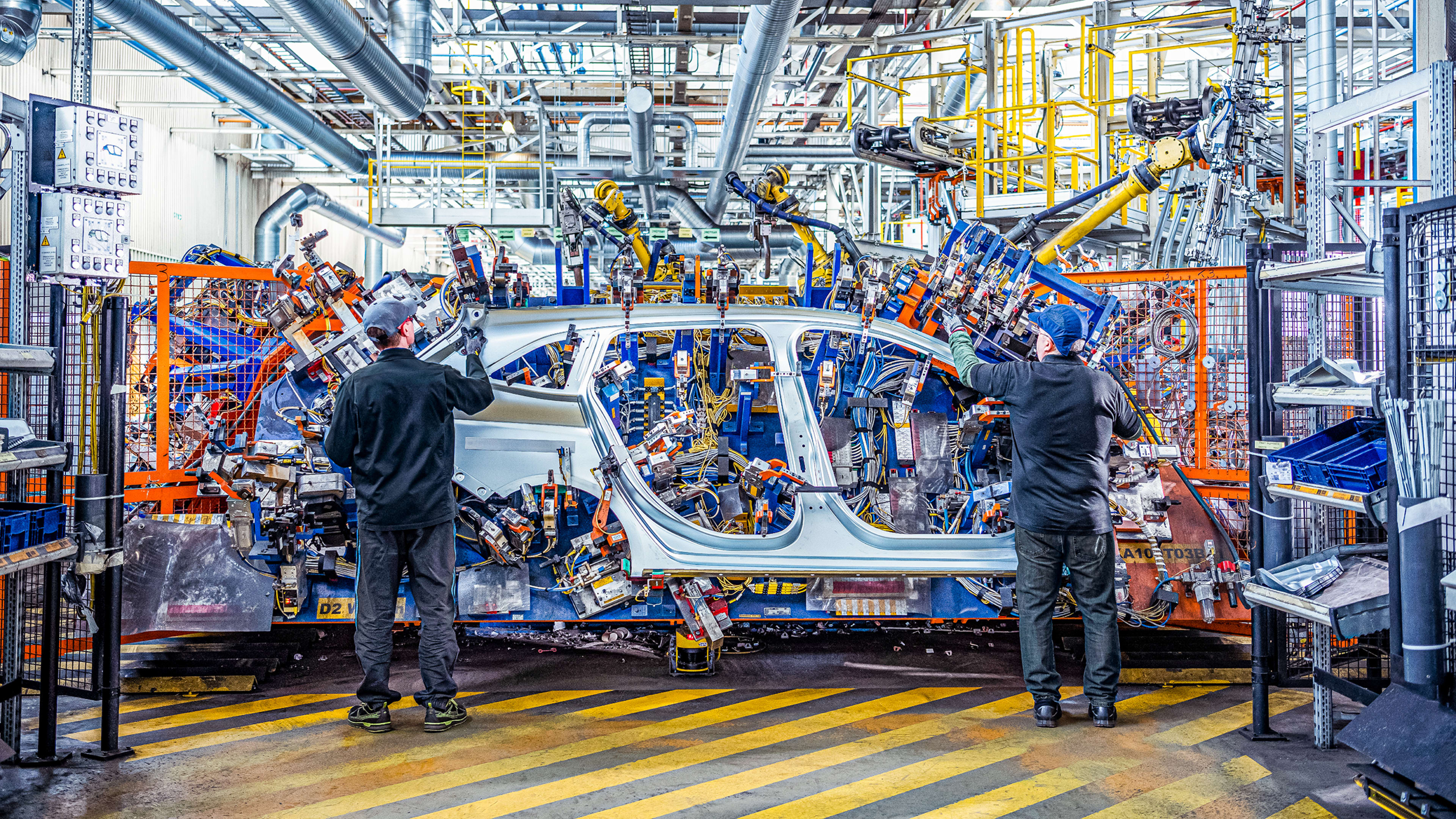

Auto workers are fighting for a slew of contract changes, including wage increases, cost of living adjustments, and the elimination of “tiers” (a classification system for workers that allows for different wages and benefits based on what date someone was hired). But another core issue has emerged around electric vehicles. According to Ford CEO Jim Farley, electric vehicles will require 40% less labor than combustion cars. EVs rely on batteries instead of engines, and most battery factories are owned by international companies, meaning they’re not part of the United Auto Workers union.

The issue has become such a sticking point that the UAW has yet to endorse President Joe Biden for reelection because he hasn’t promised a solution to ensure the clean energy transition includes union jobs. (Historically, the UAW has supposed democratic candidates.) “The federal government is pouring billions into the electric vehicle transition, with no strings attached and no commitment to workers,” UAW President Shawn Fain said in a May memo. “The EV transition is at serious risk of becoming a race to the bottom. We want to see national leadership have our back on this before we make any commitments.”

Biden did make a show of support for union jobs in a recent statement, saying, “The need to transition to a clean energy economy should provide a win-win opportunity for auto companies and unionized workers.” But Harry Katz, a labor professor at Cornell University’s ILR School who has long focused on the auto industry, says there’s not much more he can do. “There isn’t any simple direct way that Biden, Congress, or anyone can ensure that those workers at the battery factories are unionized, or even if they were unionized, ensure that they were working under terms that were as favorable as the Big Three contracts,” he says. (Katz also serves on a public review board for the UAW that hears internal disputes).

Most battery factories are foreign-owned and not unionized; if the Big Three manufacturers are involved at all, it’s only as partners: They might own the factories with another company. (General Motors and LG Energy Solution, for example, jointly own a plant in Ohio, and together they’re building two more in Michigan and Tennessee). “What can GM do?” Katz says. “GM can’t go to LG and say, ‘We order you to recognize the UAW.’”

What the UAW might get in this deal is a promise that the Big Three will remain neutral in union elections at battery plants where they have partnerships. Promises of neutrality have happened before—for instance, Volkswagen promised union neutrality at its Chattanooga car plant in 2014—but they don’t guarantee unionization. (Volkswagen abandoned that promise, workers say, and factory workers there ultimately voted not to unionize.)

The UAW concerns about wanting battery factories to be unionized, with wages and benefits similar to those at car assembly plants, are legitimate, Katz says. “I’m just not convinced there’s a way for that set of issues to be addressed beyond some form of a pledge of neutrality.”

Workers at the GM-LG battery plant in Ohio did vote to unionize with UAW at the end of 2022, but they’ve yet to reach a contract agreement. (They did, however, just win pay raises, if they ratify an interim deal.)) If the workers who build EV batteries don’t unionize, that will further dilute the power of the UAW, Katz says. In recent decades, the industry has become more fractured and complex, shrinking the UAW’s reach. More electrical components are made by suppliers that aren’t part of the Big Three and so aren’t unionized. More foreign manufacturers (or “transplant companies”), like Volkswagen, Honda, and Toyota, have been opening U.S. factories, which again aren’t part of the Big Three and thus aren’t unionized. (Attempts to unionize them, like with the Chattanooga Volkswagen plant and a Nissan plant in Tennessee, have not worked out in UAW’s favor.)

Katz’s advice to auto workers is to ramp up their efforts to organize transplants, parts companies, and battery factories. That is, of course, easier said than done. But even the current fractured landscape doesn’t mean UAW has no power. On a scale from the Teamsters, who just won a new UPS deal, to Starbucks workers, who have organized en masse but struggle to secure a contract, Katz says auto workers are closer to the former. “They’ve still got the assembly plants organized, they still have solidarity, they’re not easily replaceable,” he says. “They still have leverage.”

If auto workers ultimately do go on strike. Katz predicts it won’t be a long one. He anticipates a settlement that gives workers a pay raise, narrows that gap between the tiers, reduces the number of temporary workers, and, on the EV issue, perhaps gives an early retirement incentive to older workers, to reduce hardships of employment declines. But we’ll have to wait to see what actually happens, and Fain has indicated he’s ready to fight. “I’ve been told throughout this thing that we’ve set expectations too high,” he said at a recent rally in Michigan. “You’re damn right we have, because our members have high expectations, and record profits deserve record contracts.”

This story has been updated with information on the Ohio battery plant unionization effort and the UAW strike authorization vote.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.