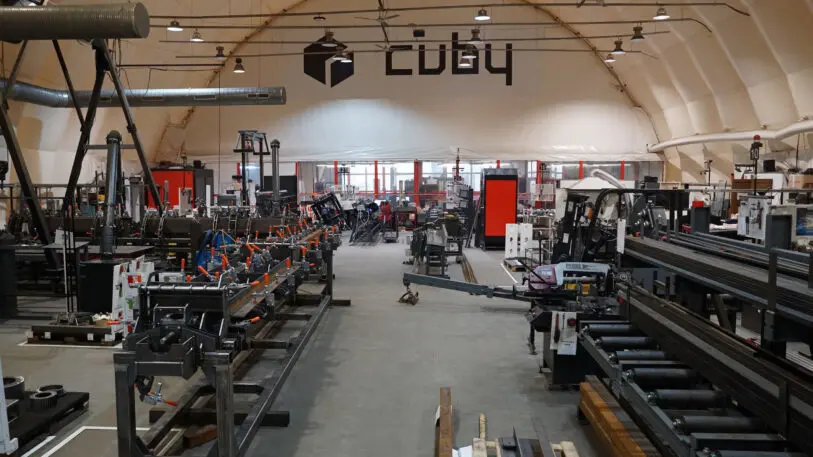

The inside of the pilot factory of construction startup Cuby is like the inside of a lot of factories doing the prefabrication of buildings: There are rows of machines and workstations and small teams of people efficiently building chunks of what will eventually be combined into a building. Such factory-based construction takes what would conventionally be built on a construction site and builds it inside a factory, making the bulk of construction more streamlined and weather-agnostic, and the onsite work more akin to assembly. Cuby is one of many companies trying to make factory-based construction a mainstream part of the way buildings get built.

But Cuby isn’t just a variation on a theme. Backed by an undisclosed amount of funding from climate tech venture capital fund At One Ventures, Cuby is trying to change how factory-based construction happens. Cuby’s product, according to cofounders Aleks Gampel and Aleh Kandrashou, isn’t the buildings that come out of the factory, but the factory itself.

During a recent tour of the factory via video call, Gampel and Kandrashou explain that their company is building the tools for prefabrication and modular building to scale up massively, including both the machines to make building components and the factories where the work gets done. Key to their approach is that the machines and the factory are all transportable.

“We launch these inflatable looking factories near or on the construction site, put our equipment inside, and we can produce at high output capacity a different kit of parts to build different building archetypes, all the way from foundation to interior finish,” says Gampel.

Looking like a pop-up Quonset hut, the factory is basically a large arch-covered plastic shed, with Cuby’s robotics and machines lined up inside. Everything, from the walls to the machines, can fit in about 20 shipping containers, enabling them to be moved to a new site and set up as a functioning factory within days.

Sold or licensed as turnkey operations, Cuby’s factories are designed to be able to produce between four and eight single-family homes per month, cutting individual building times from months to just about a week. And because the factories can be located on or adjacent to the eventual construction site, they’ve eliminated the logistical challenges of shipping building components dozens or even hundreds of miles from a specialized prefab factory. They expect costs to run 30 to 40% less than a conventionally built home.

Walking through the arched roof space of the pilot factory in Eastern Europe, Kandrashou underscores the utility of a transportable factory that can be propped up almost anywhere. “You can see,” he says as he opens a door to the outside, “this is a parking lot.”

This approach to the factory side of factory-based construction is still being tested. After three years in self-funded stealth development Cuby has produced only a few prototype homes, including the one where Kandrashou lives in Eastern Europe, but the company has a contract and permits for a single-family housing development in the suburbs outside Philadelphia. The goal, Gampel says, is to sell these $5-to-7 million factory setups to large developers who can then use them to prefabricate the pieces of their own projects, using their own designs.

“No one’s killing [construction giants] Turner or Bechtel or the groups that have been around for 200 years doing tens of billions in revenue. To compete with them you have to raise billions of dollars, you need to launch factories on day one,” Gampel says. “We thought our business model was better suited to basically help the incumbents.” Several deals with large-scale builders are currently in the works, he says.

Prefabrication and modular building has long been the construction industry’s next great idea, but many low- and high-profile attempts to scale it up have floundered or failed. There’s a notable list of historical prefab evangelists, from Frank Lloyd Wright to Buckminster Fuller and modern companies like the now-defunct Katerra that claim to have created the ideal new system for bringing the building process into the factory setting. Others are pushing aside the prospect of revolutionizing the construction industry and making a go of it in their own more limited ways, including the modular steel kit-of-parts system Bone Structure and the Berkshire Hathaway-backed MiTek Modular Initiative.

Cuby is venturing into a crowded space of contemporary innovation and investment, albeit one shrouded by many examples of a great idea not quite taking flight. “Everyone claims that they can build a building like Toyota builds a car,” Gampel says. “But putting it into practice and making it work hundreds of thousands of times over and over, that’s the hard part.”

Gampel believes that Cuby has an answer for the hard part in the form of its factories that can locate almost anywhere and that can produce building components based on their user’s designs. About half the machines in the factory are proprietary to Cuby, and they’re all designed to be used by relatively unskilled laborers, meaning that the same person who might have been pounding nails on a construction site could be operating a laser cutter or welding machine in the factory.

Like other factory-based construction startups, Cuby’s factories produced building components as a set kit of parts. Gampel says these parts are not bespoke but based directly on the most commonly used structural and building elements like wall panels and flor slabs with utilities built in. “That kit of parts is mimicry of what exists in the construction world today,” he says.

Streamlining that production and doing it on or near a construction site can bring down both labor costs and project timelines, Gampel says. “We want to be able to pop these factories anywhere there’s demand to go build a building, and to be able to execute on that using whatever local materials and local labor is available to us,” he says.

The next step is to get the first two factories up and running. Gampel says these are being set up now. He expects the project outside Philadelphia to have its first case study home up this summer.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.