September 17, 2011, was a warm, clear Saturday in lower Manhattan. I came down that morning to cover activists who gathered near the famous charging-bull statue near Wall Street to protest the injustices that led to and flowed from the Great Recession. While the crowd was modest—perhaps 700 people—its impact was amplified by triumphant tweets and video feeds beamed online using a new technology called 4G.

Marching on from the bronze idol of capitalism, protestors eventually landed at Zuccotti Park, a granite-paved plaza wedged between Wall Street and the sprawling Ground Zero construction site, where the memory of 9/11 was still fresh. Rather than going home in the evening, more than 200 diehards camped out on the hard ground, turning a half-day march into a two-month occupation and surprise media sensation.

The financial meltdown that began in 2007 had devastated countless lives; and now, finally, a protest had arisen to challenge the powers behind a warped economic system. What began in Zuccotti Park spawned occupations big and small around the country and much of the world, spreading to more than 600 locations in the U.S. and several hundred globally.

But with no formal leadership or list of demands, the only thing that held all the occupiers together was the ongoing struggle to hold public spaces. The weather began to turn, and as run-ins with increasingly aggressive police continued, Occupy felt more and more like a protest over the right to protest.

Yet the kernel of Occupy remains in the way Americans talk about economic inequality. Occupy also fired up activists who went off to a variety of movements on the left, including the Bernie Sanders presidential campaigns, Black Lives Matter, the fight for a living wage, and climate-change activism. It also helped pioneer the use of social media as a medium for protest with reach far beyond that of any in-person event.

In short, even though Occupy didn’t last long, its lasting influence is all around us.

Changing the Story

Occupy introduced a different kind of protest to the U.S., by creating space and time for anyone who wanted to discuss a plethora of grievances—most of them about money. While covering the movement, I heard talk about campaign finance, banking regulations, tax policy, student loan debt, bank bailouts, and the federal budget. The overriding theme: Regular people were getting screwed while an elite group—roughly the richest 1%—was making a killing.

This created a new political vocabulary by establishing “one percent” as a universal moniker for an elite class that runs the game. And it created a sense of common cause among the 99% who felt left behind. “Occupy [put] inequality in class back in the discussion,” says Doug Singsen, an art history professor and union activist who was on Occupy’s labor outreach committee in New York City. “There had been virtually no discussion of class in mainstream U.S. politics for, really, decades, which was also a time of rapidly increasing inequality.”

Occupy even inspired a New York City hacker collective to attack the global financial system—at least on a TV show. The Emmy-winning Mr. Robot illustrates how the class struggle of Occupy pervaded popular culture. “There’s a powerful group of people out there that are secretly running the world . . . the top 1% of the top 1%, the guys that play God without permission,” says lead character Elliot at the start of the series.

On the left, once-fringe concepts like socialism and wealth redistribution are front and center. Longtime conservative Democrat Joe Biden has teamed up with Democratic socialist Bernie Sanders to draft a $3.5-trillion spending bill that will fund clean energy development as well as massive social programs, including affordable-housing subsidies and free childcare and community college. They would pay for it, they say, with taxes on corporations and the 1%.

That bill “is assuredly a response to the searing and soaring inequalities brought to the public attention by [Occupy Wall Street],” says Columbia University economics professor Jeffrey Sachs, an Occupy booster whose research on inequality laid some of the intellectual groundwork for the movement.

The fate of the bill is uncertain. But the fact that it’s gotten even close to passing marks a major shift in U.S. politics.

Debating demands

Occupy left a pretty big legacy for something that started with an email. In July 2011, Canadian anti-consumerist magazine Adbusters sent what it called a “tactical briefing” to its mailing list. The dispatch proposed a 20,000-person, multi-month occupation of lower Manhattan to demand a presidential commission charged with getting money out of politics.

But it also invoked that year’s leaderless, consensus-based movements of the Arab Spring in the Mideast and the anti-austerity protests in Europe, in which “the movement collectively decides its own destiny,” says former Adbusters editor Micah White, who developed the briefing with magazine founder Kalle Lasn.

The occupation idea fired up people’s imaginations; the idea of a single demand, less so. There were too many problems in 2011 to focus on just one, says Chris, a business journalist who asked that we not publish his last name. “It’s a bit more of a spaghetti,” he says. “We’re talking about the multifarious tentacles of the global financial system.”

Chris and I met on August 2, 2011, when he and about 50 other people gathered at the bronze bull to see if they could turn an email into a movement. Chris is an anarchist, and he found like-minded people at the bull that day. One of them was Georgia Sagri, a veteran of the anti-austerity protests in Greece. She convinced the group to join in a “general assembly” (GA)—a consensus-based governing body that became the backbone of the movement.

The consensus model made it hard for Occupy Wall Street to get too detailed in its demands. The more specific a measure got, the more potential to lose people. But there was a bigger challenge than that: Anarchists are reticent to back specific reforms to the political or economic systems because they reject those systems outright.

Another person at the bull that day was David Graeber, a professor of anthropology and a prominent anarchist thinker (who died in September 2020). He explained in a November 2011 essay for Al Jazeera why anarchism and concrete demands weren’t compatible. “One reason for the much-discussed refusal to issue demands is because issuing demands means recognizing the legitimacy—or at least, the power—of those of whom the demands are made.”

Occupy took plenty of criticism, including from some occupiers, for not coming up with a concrete set of demands. “We felt very much like, we have the message, the public gets it, and they like it. Now let’s do something,” says journalist and former Zuccotti resident Michael Levitin. “But you can’t do that with unfocused, anarchistic, every-person-for-themselves, zero-authority kind of activism.”

Collinge affixed a sign to his tent at Zuccotti with the specific demand that Congress restore bankruptcy protection to student loan debt. It even listed a House of Representatives bill number.

Today, Collinge says that there “were some very serious people in that park who had been fighting for one issue or another for their entire adult lives.”

The hashtag movement

Though they would never agree on specifics, the occupiers were united on the overall theme of the people versus the oppressive elites. And they skillfully employed nascent technology to get the message out.

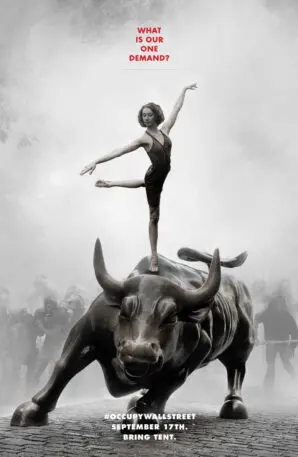

It all started with a meme. Included in Adbusters’s tactical briefing was an image of a ballerina perched atop the Wall Street bull—a captivating contrast of grace and poise with the fierce charge of capitalism. It probably did as much as any words in the email to inspire a sense of rebellion—without being specific enough to leave out anyone or any cause.

Well before the protest began on September 17, 2011, the momentum grew on Twitter with the #OccupyWallStreet hashtag and on Reddit in groups on anarchism, socialism, and libertarianism. People who identified with the hacker movement Anonymous hyped the upcoming protest over Internet Relay Chat (the Discord of a decade ago).

“One of the things that the movement did is popularize the idea of organizing online and creating movements online that defined a community, using hashtags to find topics of conversation,” says Lorenzo Serna, another member of that first GA. “If you look at all the movements that followed, they’re all hashtags.”

Online video was another staple of Occupy. The nascent movement got a huge boost from an Anonymous YouTube clip that echoed the Adbusters’s call to occupation, complete with its own vague demand: “We want freedom.” Then a YouTube video of protestors staging a pre-Occupy sleepover—and getting arrested—drew more national media coverage.

From September 17, live video coverage was integral to Occupy. That’s when I saw Serna wearing a 4G laptop hanging on a neck strap while another occupier carried a connected video camera. (This was long before the days of just clicking “Live” in the Facebook app.)

Serna worked with the group GlobalRevolution.TV, which put out steady livestream coverage of Occupy events like marches and general assembly meetings and even the eviction from Zuccotti. The team didn’t just provide endless raw feeds, though. It curated content by also following hundreds of feeds that others were streaming from around the world and featuring the best.

“We popularized livestreaming,” says Serna, who went on in 2015 to cofound Unicorn Riot, a nonprofit media group that covers social and environmental movements.

Online video captured seminal moments that advanced Occupy. After a rally in New York’s Union Square Park, a standoff ensued between activists and the police. At one point, an officer suddenly shot pepper spray at two women, who fell to the ground, screaming in pain. Another video team, the Other 99, posted a clip of the attack online, igniting national outrage and winning more recruits to the cause.

(One member of the Other 99, Tim Pool, went on to become one of the most popular YouTubers among right-wing viewers.)

Out of Occupy

By its anarchist design, Occupy Wall Street wasn’t going to solve any political problems. But it did compile a list of such problems—both officially in its Declaration of the Occupation of New York City, and unofficially in the many ideas swirling around the movement. And Occupy brought together coalitions of people who went on to tackle many of those issues.

“It makes sense that people would have come through Occupy, become radicalized, exposed to different things, and then come out, working in different movements, different struggles,” says filmmaker Marisa Holmes, an Occupy cofounder and tireless facilitator of the long GA meetings at Zuccotti.

Levitin provides a thorough list of these spin-off projects in his new book, Generation Occupy. It traces alumni of the movement who went on to causes including the Bernie Sanders presidential runs, Black Lives Matter, climate-change activism, Walmart worker campaigns, anti-pipeline and anti-fracking protests, and efforts to tighten banking regulations.

Some are clear outgrowths of the movement. The most tightly bound was Occupy Sandy, a rapid response to the devastation that Superstorm Sandy wrought on New York City on October 29, 2012.

The Occupy network set up hubs at two Brooklyn churches to collect and distribute donations, orient volunteers, and prepare food. Occupiers coordinated logistics online, such as building a database of volunteers and arranging van pools to take victims to shelters. They also helped to gut water-damaged homes and remove mold. Thousands of volunteers took part.

Also in 2012, former occupiers founded the organization Strike Debt. Through crowdfunding, it purchased bad loans at pennies on the dollar and forgave tens of millions of dollars of medical debt, student loans, and other debts. (The group has since evolved into the Debt Collective, which advocates for canceling student debt.)

Other Occupy spin-offs are linked through personal connections. For instance, Levitin’s book traces the journey of Zuccotti occupier and environmental activist Evan Weber, who went on to cofound the climate-change advocacy group Sunrise Movement.

Micah White draws a line between what came out of Occupy versus what the movement originally intended. “I’m happy with whoever wants to claim a part of the legacy of Occupy and say that it gave them a boost,” he says. “But the truth, from my perspective, is that those are unintended consequences.”

Making way for Bernie

Both the rhetorical power and the personal energy of Occupy came together in the rise of Bernie Sanders. “Occupy Wall Street was mostly successful as a way of changing hearts and minds rather than elections or policy,” says Charles Lenchner, who served on the Zuccotti tech-ops working group. “But the consequence of that changing of hearts and minds is what sets the stage for Bernie Sanders’s rise.”

The Sanders team gave a qualified compliment to Occupy activists during the 2016 campaign, when spokesman Karthik Ganapathy told CNN, “Occupy Wall Street helped create the political climate that helped Bernie’s message to resonate so widely, simply by shining a spotlight on issues of Wall Street greed and income inequality.”

That doesn’t make Sanders the Occupy candidate, though. “We were against representative politics, we were against electoral politics,” says Occupy cofounder Holmes. At least some people were. “There were lots of people from Occupy Wall Street supporting [Sanders’s] campaign,” says Chris (who was not one of them). “And that represents a great rift that had always been around, basically between the usefulness or uselessness of electoral politics.”

On the pro-politics side was Lenchner, a professional organizer for nonprofits and political causes like the Dennis Kucinich presidential campaign and the Working Families Party. In 2013, he and fellow progressives were looking for an alternative to Hillary Clinton in the coming presidential election. “[Elizabeth] Warren was a favorite of Occupy because she was actually pointing the finger directly at the Wall Street industrial complex,” Lenchner says.

The result was a group, Ready for Warren, composed almost entirely of Occupy alums. It launched a Facebook page, hired a director, printed signs and banners, and even threw an unofficial campaign party after a Warren speech in New York City. None of this was coordinated with Warren’s staff, who warned the group to back off.

By March of 2015, it became clear that Warren was not ready to run for president. So Lenchner polled the group on what should be done next. About half voted to shift support to Sanders. They reached out to the Vermont senator’s staff, Lenchner says, and got a heads-up that Sanders was about to announce his intention to run for president (in a speech that would name-check the 1% and proclaim inequality as “the major issue” in America).

That provided a few days to build a website for their new group, the People for Bernie Sanders. The site announced 99 campaign events to be held around the country—a number that grew to about 250, Lenchner says. And they soon revealed the famous “Feel the Bern” slogan that became a staple of the Sanders campaigns. Lenchner says that the group’s main Facebook page generated about 4 billion engagements in the 2016 run alone.

All this happened independent of Sanders’s official campaign. The People for Bernie essentially laid the social media foundation for the Sanders candidacy well before Sanders’s own campaign had ramped up.

Sanders’s two campaigns failed to win the nomination, but they helped move politics farther to the left—in the direction that the politically minded contingent of Occupy had been pointing. And Sanders in turn made way for more left-wing politicians by boosting the Democratic Socialist movement.

During + after the 2008 financial crisis, everyday people started to viscerally see the corrosive role of lobbyists writing in legal loopholes that allowed big banks to gamble with people’s lives and the economy as a whole.

Occupy Wall Street emerged, and activism bloomed.

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) January 16, 2019

One of them, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Democratic representative of New York, now sits on the powerful House Committee on Financial Services that oversees Wall Street. And she credits Occupy with kicking off a series of events that made it possible for reformers like her to get into positions of power. “Occupy Wall Street emerged, and activism bloomed,” she tweeted after her appointment in 2019.

From Zuccotti to Ferguson

While people today might need reminders of what Occupy Wall Street was, everyone has heard of Black Lives Matter, a movement that started not long after and has retained its high profile among supporters and detractors alike. But the two phenomena have close connections.

It goes back to August 9, 2014, in Ferguson, Missouri, when a young man named Michael Brown got into an altercation with young police officer Darren Wilson. A scuffle and chase ensued, and Wilson fatally shot Brown. Tensions between Ferguson’s Black community and the police were already sky-high after years of abusive policing. And Brown’s killing set off months of protest that propelled the nascent Black Lives Matter cause into a major national movement.

The protest actions in Ferguson were spontaneous and decentralized. “We weren’t members of an organization,” says DeRay Mckesson, a school administrator who left his home and job in Baltimore to join the actions. “We were people who largely met in the street and became organized as activists together in the street.”

Traditional activist organizations tried to advise the Ferguson protestors, Mckesson says, but their advice was geared to a movement with a formal organizational structure, conducting orderly protests—not a decentralized mass of activists running from tear gas. “They did not have the skill to help us in the middle of chaos,” Mckesson says.

But Black Lives Matter was growing into a powerful hashtag movement, and it was on Twitter that Mckesson and fellow protestors found help. “It was Occupy people on Twitter who just knew the most about what to do in nontraditional organizing,” Mckesson says. The decentralized, leaderless aspects that had proved so challenging to the coherence of Occupy provided the lessons that Black Lives Matter needed to coordinate in its early days.

And Occupy’s scuffles with police, which some criticized as a distraction to the movement, provided key tactical knowledge. Over Twitter, occupiers shared lessons such as how to avoid being surrounded by police in “kettling” techniques or how to protect themselves from tear-gas attacks. Occupiers also taught BLM about technologies, such as the encrypted messaging app Signal; and they advised on outreach to the news media.

Occupy alumni were just one contingent among many in BLM, but “there was definitely a migration of sorts from the Occupy networks into Black Lives Matter,” says filmmaker Holmes. “I would be in the streets and see all the same people.”

Occupy today

There will be a series of events in New York and other cities like Boston and Los Angeles to commemorate the 10th anniversary of Occupy Wall Street. Some die-hard activists have remained true to the cause all these years. You can find them posting and discussing on several Facebook groups and Twitter accounts.

But most occupiers moved on long ago. And the environment has changed a lot in the past decade, calling for a new kind of response. The rise of candidate Trump in 2016 remade the political landscape, and the rise of COVID-19 in 2020 remade it again.

One example: In response to the pandemic, the federal government paused collecting on student loans. “And the government is scared shitless to restart the lending program because they know that whenever they do, almost nobody is going to pay,” says Alan Collinge.

Now in his 16th year heading Student Loan Justice, Collinge has started a runaway-success petition calling on President Biden to simply cancel federally owned student loans, which make up the vast majority of college debt. The idea has gained support from Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

Collinge was a die-hard occupier who adored his Zuccotti experience. But Occupy did little to boost his cause, whereas COVID-19 may provide the push.

The pandemic has also changed the nature of protests. Masses of people living for months in close quarters is unthinkable today, at least among the lefties who would support any kind of Occupy redux.

But occupation was becoming a tired concept even by the end of 2011. “I don’t think that was the end goal, to have mass housing in a public square where it’s really uncomfortable,” Holmes says. “I generally wanted to move into the neighborhoods” (meaning closer to communities).

Holmes helped launch something like a local revival of Occupy in 2016, when she and other New York City anarchists formed what she calls a “united front against fascism” to oppose the political right. It coalesced into the Metropolitan Anarchist Coordinating Council, which runs along the same lines as Occupy, with consensus-based assemblies and working groups. But no one’s living in parks.

Lorenzo Serna shares the goal of moving into the community and questions the online-heavy aspect of Occupy, noting “At the end of the day, all that change has to happen in our communities, to happen in our neighborhoods. And those things will be done on the ground with our feet, talking to people. And it doesn’t matter how many likes the thing gets on the internet.”

Serna is now media director for the NDN Collective, a group that promotes Native American communities in their efforts to develop and in their struggles against resource extraction on native lands. “We have a bunch of really spread-out communities. They’re really rural,” Serna says. “But using live media, we’re able to bring people to places that they wouldn’t be able to get to.”

And Micah White, who sparked the idea for Occupy, now rejects the very nature of political protest. “The deeper lesson of the defeat of Occupy is that Western governments are not required to comply with the people’s demands,” he writes in his 2016 book, The End of Protest. Once a believer of protesting to effect change within the political system, White now focuses more on changing the “mental environment,” to create a bigger societal change than just getting the right person elected.

But White is still proud of what Occupy did accomplish—providing momentum at a time when activism on the left had slumped, and defying a narrative that millennials were uninterested and apathetic. “I think that Occupy shattered that [narrative], and that’s been one of the lasting impacts,” he says.

However the environment and tactics have evolved, Occupy does leave behind a dedicated corps of activists looking to change the world, though they may have different notions of what that change should be.

“I have no intention—and I think a lot of people have no intention—of stopping,” says Holmes. “This is what our lives are about. I’m in this forever.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.