Architects and doctors speak two different languages. One is spatial, the other medical. So when they need to work together to plan out the physical space where medical care takes place, a lot can get lost in translation.

A new toy-based design toolkit developed by the design and engineering firm Stantec aims to make the process of designing medical spaces more intuitive for both designers and doctors. Using familiar Playmobil human figurines and a library of scaled-down 3D-printed furniture and equipment, the toolkit puts the process of shaping the space into the hands of those who’ll be using it.

They’ve put this toolkit to use on a redesign project for the surgery and examination rooms at the Mary Bird Perkins Cancer Center, an outpatient facility in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The center needed to rethink the spaces shared by three different teams of specialists, one focusing on speech-related issues, another focusing on cancers affecting the head and neck, and a third that conducts surgeries on cleft palates and other oral issues. The assumption going into the design process was that each team used the exam room differently and so would have different spatial needs.

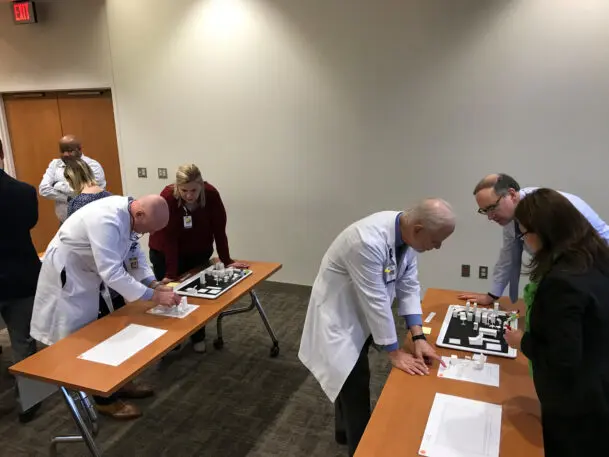

[Image: courtesy Stantec]After some discussions about how they use the space, each team was given its own toolkit to physically mock up how they imagined an ideal exam room. Using the Playmobil figures and 3D-printed mini versions of common equipment such as surgery tables, chairs, and lights, the doctors began building their own models of rooms that would work best for their needs.

“The level of engagement that was going on was fascinating,” says Todd Stevens, president and CEO of the Mary Bird Perkins Cancer Center. “I’ve been in a bunch of meetings on space design with physicians over my 30-year career in cancer care. And up until this session, they all kind of looked the same. They were productive but frustrating at the same time because you knew there was more to it and more engagement that you could pull out of the physicians.”

[Image: courtesy Stantec]Stevens says the toy-based design exercise got the clinicians to more precisely think about how things such as tables and mobile equipment could best be placed and stored, bringing much more specificity to the design compared to a verbal explanation.

And though each of the three teams of clinicians has a different focus area, the prospective floor plans they came up with using the toolkit ended up looking almost the same. “There was a lot more consensus visually when the three teams stepped back and saw, ‘Wow we could do things more similar than different,'” says Stevens. “That was a striking revelation.”

Their designs even ended up revealing ways the renovated rooms could save some space, by using doors that slide instead of swing open, and better understanding what equipment needed to be in the room at all times and what could be stored elsewhere. The savings added up to maybe 10 or 20 square feet, but when that gets multiplied over several exam rooms, the redesign will free up significant space for other needs at the cancer center.

The exercise was also helpful for Stantec’s designers. “We get to discover things that we didn’t even realize they’re doing,” says Stantec senior medical planner Maria Barillas. For example, seeing that different doctors were moving lights and equipment in and out of rooms depending on the procedure helped inform how and where they should be stored. “You allow them to take the drivers’ seat.”

This design exercise happened before the pandemic, and Stantec’s designers haven’t yet been able to try it again, but they expect that it will become a part of their design process. Barillas says the toolkit could be particularly useful on school projects as well as other healthcare-related designs.

For the Mary Bird Perkins Cancer Center, the pandemic has also stalled the implementation of the designs developed through the use of Stantec’s toolkit. Stevens says that he’d want to see this kind of toolkit-based exercise on any additional design or renovation projects that the center undertakes in the future. “If the architecture firm that we end up partnering with doesn’t do this as part of their discovery, we probably wouldn’t work with them,” he says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.