At the end of March, I was supposed to attend a dinner party where the core topic of discussion was how online collaboration could tackle diseases that are traditionally ignored by Big Pharma. Instead of wine and good food, experts from the National Institutes of Health, Harvard University, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and I were forced to settle in at our home offices and dial into Zoom. In some ways, it was the perfect format to discuss how open-source tools could help find new cures.

“Obviously in the current context, everybody is thinking about how do we develop therapies, how do we develop vaccines, how do we develop all sorts of things for COVID-19,” said Ashish Jha, director of Harvard’s Global Health Institute. The question now before the group was how researchers could use their collective brainpower to quickly and cheaply devise viable treatments and vaccines for a pandemic that is ransacking the world.

The response to COVID-19 has been more open-source than any drug effort in modern memory. On January 11, less than two weeks after the virus was reported to the World Health Organization, Chinese researchers published a draft of the virus’s genetic sequence. The information enabled scientists across the globe to begin developing tests, treatments, and vaccines. Pharmaceutical companies searched their archives for drugs that might be repurposed as treatments for COVID-19 and formed consortiums to combine resources and expedite the process. These efforts have yielded some 90 vaccine candidates, seven of which are in Phase I trials and three of which are advancing to Phase II. There are nearly 1,000 clinical trials listed with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention related to COVID-19.

The response to COVID-19 has been more open-source than any drug effort in modern memory.

The gathering of resources and grassroots sharing of information aimed at combating the coronavirus has put open-source methods of drug development front and center.

“It’s our moment,” said Bernard Munos, a former corporate strategist at pharma company Eli Lilly, who has a graying academic’s mop. Munos has been arguing for an open-source approach to developing drugs since 2006. “A lot is at stake because if it’s successful, the open-source model can be replicated to address other challenges in biomedical research.”

In recent history, pharmaceutical companies have failed to deliver treatments for devastating illnesses because they cannot easily profit from them. While they may investigate diseases for which there is no treatment or cure and even find compelling insights, they won’t necessarily turn those findings into medicine. Furthermore, all that discovery stays locked away in proprietary company files, which means no one else can take these learnings to the next level. This has led some scientists and researchers to advocate for a more open approach to drug development. Despite interest, open-source medicine has only materialized in one-off projects.

But a human rights lawyer named Jaykumar Menon is now building out a platform where scientists and researchers can freely access technological tools for researching disease, share their discoveries, launch investigations into molecules or potential drugs, and find entities to turn that research into medicine. If the platform succeeds, it would allow drugs to succeed on their merit and need, rather than their ability to be profitable.

As COVID-19 brings the world’s scientists together and demonstrates the need for faster drug development, Menon’s early success shows the promise of collective research. Still, Open Source Pharma Foundation has only one drug candidate so far, and it could still fail in subsequent trials. At the dinner turned Zoom meeting, the group of public health and pharmaceutical luminaries picked apart the idea of an open-source drug platform to see if it had potential. An open-source platform for medicine could energize drug development and allow scientists to collaborate on research for diseases such as COVID-19. But for such a platform to become a truly global tool, it will have to contend with the broken, profit-oriented drug development system in the United States.

A Linux for drug research

In a 2006 Nature article, Bernard Munos asserted that taking an open-source software approach to drug development could make the pharmaceutical industry both more productive and more innovative. He called it a Linux for drug research and development, likening his idea to the famed open-source operating system.

“It is possible to offer scientists a computerized toolbox that lets them harness the creativity of numerous volunteers to address the key questions that are holding back innovation,” he wrote. Under such a paradigm, researchers, scientists, and even doctors—who sometimes find novel uses for drugs by prescribing them to address issues other than their original purpose—could freely contribute to a variety of research projects.

Munos believed a new way to develop drugs was necessary because the pharmaceutical industry was simply not meeting the demand for drugs. Then as now, pharmaceutical companies have focused on making drugs that draw over $1 billion in sales. These so-called “blockbuster” drugs, which include cholesterol medication Lipitor and arthritis medication Humira, tend to have a wide patient base. He suggested at the time that an open-source platform could help spur drug discovery for more diseases and possibly push research into areas pharmaceutical companies were not motivated to engage in.

Bernard MunosIt is possible to offer scientists a computerized toolbox that lets them harness the creativity of numerous volunteers.”

However, as patents for blockbuster drugs have expired, enabling generics manufacturers to produce them for significantly lower prices, pharmaceutical companies have turned to developing drugs for rare diseases—research that was formerly dismissed due to a smaller return on investment. But these new drugs can take 10 years or more to develop, leading pharma companies to attach huge price tags to them.

Munos thought crowdsourced research could bring down some of that cost and speed up timelines. However, how much an open-source approach can actually cut costs is unclear. As Munos noted in his seminal paper, writing code or improving on software only requires a laptop and a network connection, but there are hurdles to erecting a Linux or GitHub for drugs. Biology is far more complex than computer software, with lots of opportunities for missteps. In addition, much drug research and talent remain stuck behind pharmaceutical company walls. Drug manufacturers often insist that scientists and researchers only work on research owned by the company—even if it’s done off-hours.

As of yet, a single big open platform hasn’t emerged. Instead, partnerships between government agencies and industry players have been the primary vehicle for open-source medicine. Organizations such as Medicines for Malaria Ventures and big publicly funded initiatives such as the Human Genome Project have made impressive gains using open-sourced approaches. A 2011 estimate from the Battelle Technology Partnership Practice says the Human Genome Project, which spent $3.8 billion between 1990 and 2003, led to an economic impact of $796 billion.

But public-private partnerships have also been limited in their ability to fully engage open-source methods to the degree that Munos laid out in his proposal. Because these projects focus on research, not on creating health products, there’s no guarantee a third party will take up the findings and turn them into something that actually fights disease.

In addition, running a successful open-source platform is not just a matter of having a good product. “It also takes a leader who can connect with people, understand their motivation, and foster trust,” Munos wrote. He points to Linux founder Linus Torvalds, who drove the development of the Linux platform and whom the community trusted deeply.

“Intractable human problems”

On Zoom, Jaykumar Menon’s long face hovers in front of a darkened Earth, its perimeter illuminated by a rising sun. “If you’ve ever heard of the overview effect, which is when astronauts look back at planet Earth and have a spiritual experience and realize the oneness of humanity—perhaps this is a similar moment for us,” he says.

In person, Menon is tall and thin and forever hiding a mischievous grin. His lightly grayed dark hair always seems rumpled. In addition to founding Open Source Pharma Foundation, he is a senior fellow at Harvard University’s Global Health Institute and the cofounder of India Nutrition Initiative, a group that has fortified salt with iodine and iron. Before he became fixated with public health, he practiced human rights law. “I’m sort of fond of trying to solve intractable human problems,” he tells me.

Even when he was practicing law, Menon was targeting problems using collective intelligence. In 2000, he became the 15th lawyer in 14 years to take on a wrongful conviction case involving David Wong. Wong was charged with murdering another inmate while serving a lesser sentence. Nearly every lawyer before Menon had filed complex motions alleging procedural flaws in Wong’s original case.

Jaykumar MenonI’m sort of fond of trying to solve intractable human problems.”

“We pursued a different approach,” says Menon. “Why don’t we try and find who the real killer was?” Menon worked with a private investigator, known for brandishing a Bible and a gun, to track down murder witnesses. He also had the support of the David Wong Support Committee, a group he credits heavily for the case’s outcome.

“The remarkable thing about the case was not the legal part, but this community of people that grew up around Wong, citizens who did some of the investigation, who helped fund the legal work, and who helped support Wong,” Menon says.

The tactic required a lot of brute force—tracking people down, asking them questions, gaining their trust—and relied on the contribution of many to reach a final outcome. It is a similar strategy to the one Menon is applying to Open Source Pharma Foundation. However, rallying a group is never an easy task, and creating a platform that enables this kind of collaboration may present more challenges than potential.

Early on during the Zoom dinner, there was skepticism that an open-source pharma platform could scale effectively. Menon’s idea seems to have worked for metformin, but there were questions as to whether it could do the same for other drugs.

However, repurposing isn’t always so easy. During the Zoom call, a member of the NIH noted that while drug repurposing can be cost-effective, it usually isn’t. In many cases, the drug being repurposed was approved so long ago that the data associated with the original research is either out of date, difficult to get, or costs lots of money to license.

Still, Menon’s repurposing of metformin is inspiring and gives hope for other drugs developed on the OSPF platform. To do it, he used a drug that was still in production and generic, meaning he didn’t have to obtain approval from a pharmaceutical company to use it. And secondly, he didn’t change the dose of the medicine, which meant he could lean on existing safety and dosing trials for metformin and move straight onto efficacy studies. Menon argues that any repurposing work done on the platform should only look at drugs in the public domain that are still in production and should ideally use an already approved dosage.

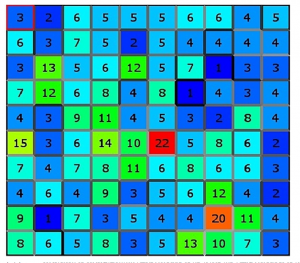

Using Menon’s approach could lead to more successes, but there may be few drug candidates that fit the mold. A 2018 study from Cambridge Judge Business School on drug repurposing found that about 31% of drugs approved by the FDA had the potential to treat an illness similar in nature to the original target disease (for example, reusing a liver cancer drug to treat stomach cancer), with a 67% success rate. It is even harder to repurpose a drug to treat a fundamentally different disease than the one it was originally intended for, as OSPF did with metformin. Researchers found that only 18% of drugs had potential in that capacity, with a 33% success rate.

Mike StebbinsWe have a massive market failure in the center of our biomedical research enterprise.”

These are some of the details that could chip away at the feasibility of an open-source pharma platform. And then there are larger concerns:

“We have a massive market failure in the center of our biomedical research enterprise,” said Mike Stebbins, a geneticist and former assistant director for biotechnology at the White House Office of Science and Technology under President Barack Obama, on the Zoom call. “Coming up with a handful of models is not going to really relieve that.”

Instead, Stebbins believes the government needs to step in. Someone on the Zoom call noted that a government agency devoted to developing therapeutics is a logical and cost-effective approach, but it hasn’t happened yet.

“You need a disaster,” said Stebbins.

“Well, we have one of those!” another participant said.

The building blocks of open-source drug discovery

Weeks earlier, before social distancing became mandatory, I visited Open Source Pharma Foundation’s offices in New York City. Menon works inside a stately former school on the Lower East Side that has been taken over by a nonprofit performing arts organization called the Clemente.

To get to his office, I walked up to the second floor and through a small cabaret theater with three rows of red velvet chairs on a set of risers. Past that is a small room with three desks belonging to the theater’s executive director, who allows Jaykumar to work at a nearby table.

We settled in down the hall in a room with ballet-studio-esque mirrors along one side and a chalkboard on another. Nick Krenteras, a college friend of Menon’s who now works in private equity and venture capital, joined us at a large folding table. Krenteras and Menon were discussing how to draw users to an open-source platform for pharmaceuticals, how to sustain such an operation financially, and how to convince Big Pharma to participate and share knowledge.

“The phrase we’ve gotten a lot of traction off of is, ‘GitHub for pharma,'” Menon says, referring to the platform that developers use to share open-source code. “People understand what GitHub is.”

Jaykumar MenonThe phrase we’ve gotten a lot of traction off of is, ‘GitHub for pharma.’”

“I think it’s a good frame, but I don’t know how much it reflects reality,” Krenteras says. A drug isn’t pieced together like software—it’s suggested and vetted across a crowd. Software can be divvied up into chunks, where one person can write a mouse driver while another handles the graphics display; drugs cannot. “You can’t have half a drug.”

“What if we make the LAMP stack for pharma?” Menon suggests. LAMP is an acronym for Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP—the layers of software that power a great deal of open-source web application development.

This analogy better reflects Menon’s goal to launch free drug-discovery software powered by artificial intelligence, which is ordinarily immensely expensive. Already, he’s garnered a commitment from Harvard University to build out the software’s back end and host the eventual software. This would allow researchers to use public data and the platform’s repository of crowdsourced information to search for novel molecule candidates and repurposable drugs. The final goal is to offer a platform where biomedical projects can be floated, crowd-researched, and produced.

Menon believes providing free software for drug discovery could create an incentive for joining OSPF. However, he doesn’t want to give up a slate of free tools to everyone. Big pharma companies and researchers would have to share information to get the free software—or pay. The access fee could then sustain the costs of building out and operating the platform, while making it accessible to more people.

“We have this global movement of students and people in low-income countries, and they just cannot afford that software,” Menon says. He believes that hosting it for free would radically democratize the drug discovery process.

The challenges of fixing a broken system

Menon estimates it will cost as much as $1 million to get to the end of Phase 2B in the metformin clinical trials. In this case, India’s National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis is paying much of the cost and conducting the metformin trials in hospitals around India. At the moment, it’s unclear who will pay for the development of other drug candidates that come out of the OSPF platform.

For the platform to actually bring down the costs of drug development and in turn the price of drugs in the U.S., it will have to contend with the complex issues that surround drug pricing. Drug costs remain high because of a trifecta of issues at the heart of the health industry market: The cost to develop a drug is growing, the payer system doesn’t reimburse for new expensive treatments, and the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t invest in truly needed areas.

Another issue is that pharmaceutical companies have a way of retaining exclusivity on widely used drugs even after their patent has expired. To repurpose a drug, a person or organization often needs the cooperation of the company that designed the drug in the first place. David Mitchell, founder of the patient advocacy group Patients for Affordable Drugs, has studied how pharmaceutical companies use a series of loopholes to maintain control of their most profitable drugs. “The system is built to benefit everybody who makes money on it at the expense of everybody it’s supposed to serve, which is backwards,” says Mitchell.

He says that pharmaceutical companies will ask generics companies to stay out of certain markets such as the U.S. in exchange for access to a smaller market. In Europe, for example, he says that generic drug manufacturers sell a drug that is biologically similar to Humira for 20% of what Americans pay in the U.S. Meanwhile, the price of Humira continues to rise in the States.

David MitchellThe system is built to benefit everybody who makes money on it at the expense of everybody it’s supposed to serve, which is backwards.”

AbbVie, the company that previously owned the patent to Humira, also uses so-called “patent thickets” to maintain control of its highly profitable drug by patenting other aspects of it. “They could patent the mechanism of delivery, if it’s a pen or an injector,” Mitchell says.

When generics are able to make it to the market, prices come down, Mitchell acknowledges. He sees how a platform focused on repurposing generics could ease some drug pricing. However, generics manufacturers are less likely to make inexpensive pills that serve a small market, because they cannot make enough money. Daraprim, a treatment for a rare parasitic infection called toxoplasmosis, famously did not have a generic competitor when former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals Martin Shkreli boosted the price to $750 per pill (Shkreli has requested a compassionate release from his prison sentence, which he is serving for securities fraud, so he can work on a coronavirus treatment).

In addition to repurposed drugs, an open-source platform could seed new drugs—though that comes with a much longer approval process. While introducing new drug candidates will help increase the potential for the development of more affordable drugs, it will not affect the cost of most drugs, which mostly come from large pharma companies with exclusivity deals attached.

At some point, the government could step in. Mitchell says he would like to see Congress cap drug prices, especially since public dollars fund at least some portion of drug development. And according to Stebbins, the ideal way to ultimately curb costs in the healthcare industry would be to let the government pay for research and development.

“The private industry has a choice, and that’s to engage in addressing these market failures or have someone else do it,” he said.

Open-source in the age of pandemic

The U.S. government currently doesn’t make drugs, though there is some political steam gathering behind the idea that it should. Stebbins is among those who, like California governor Gavin Newsom, think the government should be funding research and development for vaccines, treatments, and medical technologies. Already, the National Institutes of Health funds academic research aimed at understanding disease, but those programs don’t necessarily lead to commercialized products.

Stebbins has called for the development of a Health Advanced Research Projects Agency, or HARPA. It would function much like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which has seeded some of the greatest inventions of the modern era, including the internet and GPS. Per Stebbins’s vision, government tax dollars would be spent on health research that leads directly to medical products, and the government would have some control over the pricing of those products. He sees an open-source pharma platform as a component of HARPA. While open-source initiatives can lead to innovation, he says, such efforts need sustained, long-term financial support to preempt an outbreak such as COVID-19.

However, the prospect of the government funding the development of new medicines is politically fraught. “We’ve tried to fund the development of diagnostics and treatments, but it has been politically very difficult to get funding for those things, because it’s hard to make an argument that we should fund research for known unknowns rather than for disease we know we should resolve,” says Stebbins. The pharmaceutical industry has also been known to complain to members of Congress when groups within the NIH get too close to research that looks like it could lead to a commercial medical product.

Still, he says, if we want to be prepared for pandemics such as the current one, we have to have systems in place ahead of time. “The private sector can react pretty well, because the money will show up and I think they’re pretty confident in that,” he says. “But if you were going to do things before the COVID outbreak, you would need other incentives.”

Even so, while the effort to find a vaccine and treatment for COVID-19 has united researchers around the world, there isn’t a single, standardized way to bring all the endeavors together.

Jaykumar MenonIt’s closed, it’s chaotic, it’s locked behind company and country borders, and it does not leverage the power of the global brain.”

“Even though there’s a lot of research happening on COVID-19, it’s closed, it’s chaotic, it’s locked behind company and country borders, and it does not leverage the power of the global brain,” says Menon.

He’s now working on several tools for COVID-19, all of which launched in April. One is a simple Google sheet where scientists can put down a hypothesis for what existing drugs or mechanisms of action might work against the coronavirus. Open Source Pharma will narrow down the list of proposed candidates and model out their viability. Another project is aimed at developing early-stage vaccine candidates in partnership with the European Vaccine Initiative.

“This would include IT platforms, IT tools, scientific information commonses, training, conferences, education, social media, art, and white papers,” writes Menon—a whole social network for scientists. The opportunities are significant, he notes. Already, the government is doing a lot of research that could be made so much more accessible through a single platform.

“Health research and development and drug discovery supported or conducted by the government is funded by the public,” he writes, “and should be, almost by definition, open-source.”

What should be is not always what is. But that has never stood in the way of Menon’s determination to solve intractable human problems.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.