Over the last two decades, since its founding at the turn of the millennium, the Gates Foundation has given away $53.8 billion. In this year’s annual letter about the foundation’s activities, Bill and Melinda Gates take a look at what’s worked (vaccines) and what hasn’t (education) over the lifetime of the organization—and look forward to how they plan to give away the next billions.

“At its best, philanthropy takes risks that government can’t and corporations won’t,” they write. Governments, they argue, should focus on scaling up solutions that are already proven to work, and businesses have to think about profit, but foundations can experiment with different approaches.

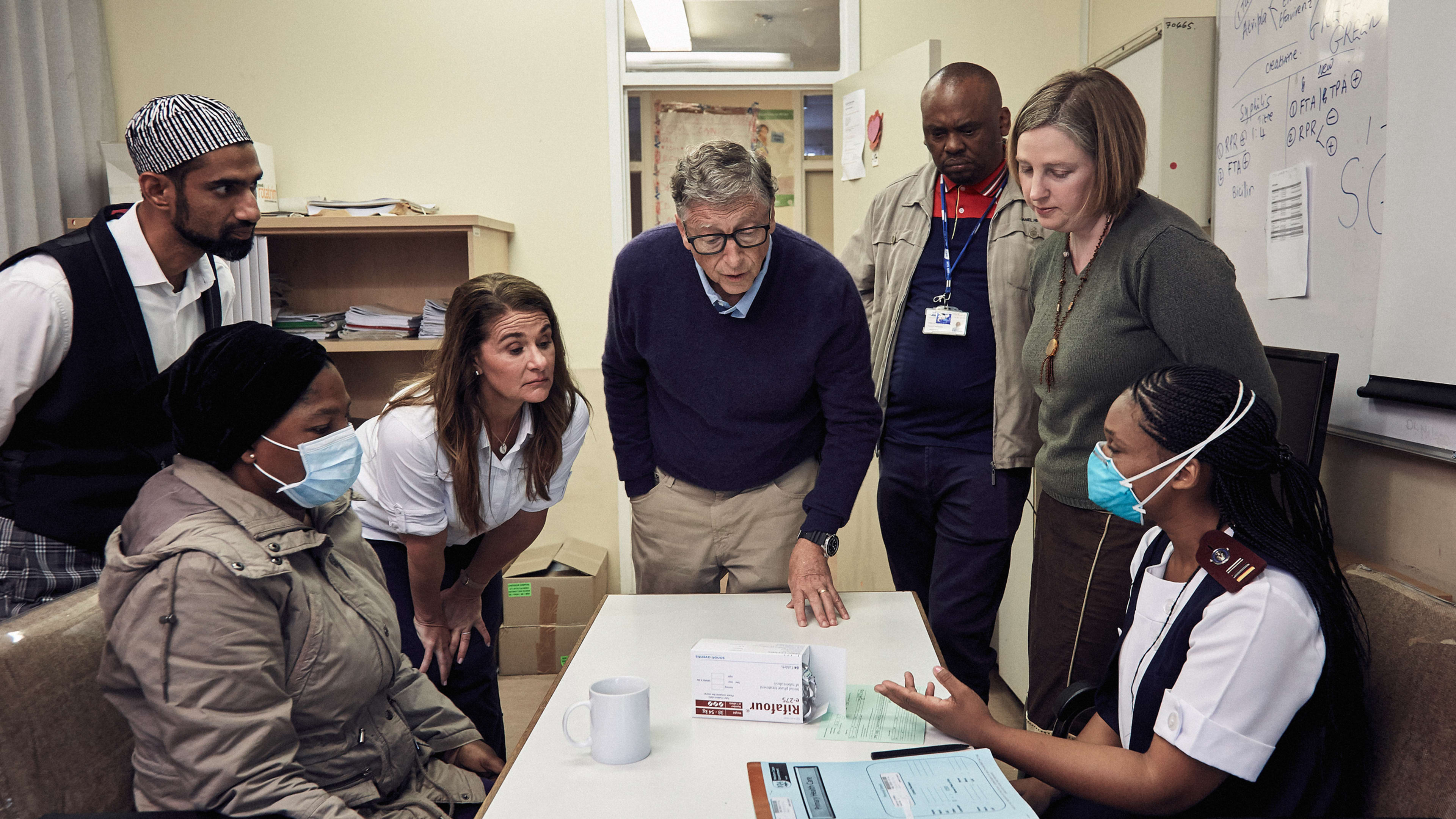

For the Gates Foundation, which has focused its efforts to date on global health and on education in the U.S., one of the first experiments involved vaccines. They realized that children in some countries were dying from diseases that were easily preventable. Through a new alliance that it created called Gavi, the foundation worked with governments and other organizations to raise funds to buy vaccines.

They didn’t know if it would work—or whether governments in low-income countries would succeed in getting the vaccines to children. But it was a success. By 2019, the program had helped prevent 13 million deaths and vaccinated more than three-quarters of a billion children. It helped bring down the cost of one key vaccine by more than 70%. Still, a segment of hard-to-reach children still isn’t getting vaccinated; the foundation now plans to work on getting basic vaccinations to all children.

Some of the foundation’s other work has been more challenging. The foundation made early bets on preventative medicine for HIV that had to be taken every day; while an effective daily preventive pill now exists, the team realized that it wasn’t something that people realistically want to use in many locations, and it hasn’t made a significant difference in preventing HIV in lower-income countries. In other cases, patients with HIV haven’t gotten treatment even when it was readily available because of the stigma. The foundation is now taking a broader look at what would help prevent the disease, including factors such as financial literacy and ending gender-based violence.

The foundation’s investments in education in the U.S. also haven’t gone as expected. “If you’d asked us twenty years ago, we would have guessed that global health would be our foundation’s riskiest work and our U.S. education work would be our surest bet,” Melinda Gates writes. “In fact, it has turned out just the opposite.” One Gates-funded effort spent hundreds of millions trying to improve high school graduation rates in a handful of states by continually assessing teachers and offering assistance, but it didn’t really help; most of the teachers were already rated as effective, and it wasn’t clear how to help teachers improve.

Overall, the letter reports, more students are now graduating from high school, but many still don’t go on to finish college. Part of the problem, Melinda Gates says, is that it still isn’t clear which interventions work best, and solutions are also hard to scale up—it’s better to tailor specific solutions to specific areas. The foundation is now focusing more effort on helping local networks of schools identify local solutions.

The foundation has sometimes been criticized for its choices; one editorial in the medical journal The Lancet, for example, argues that the Gates Foundation has focused on diseases such as malaria even in areas where other diseases cause more harm, diverting attention and resources away from necessary research. The foundation spends more on health than most countries and more than the World Health Organization but has less accountability.

Still, it’s clearly had an impact in the areas it does support, and it’s committed to continual improvement. “We now have a much deeper understanding of how important it is to ensure that innovation is distributed equitably,” they write in the letter. “If only some people in some places are benefitting from new advances, then others are falling even further behind.”

In the coming years, the foundation will also focus on two other key issues: climate change—including helping people in poorer countries adapt to the impacts caused by a changing climate—and gender equality. Melinda Gates writes that progress on gender equality has been slow because “the world has refused to make gender equality a priority.” That’s something that the sheer scale of the Gates Foundation could help change. And it plans to continue making what it calls big bets in all of its work, taking risks on solutions that may not be successful but will have an outsized impact if they are. “The goal isn’t just incremental progress,” the letter says. “It’s to put the full force of our efforts and resources behind the big bets that, if successful, will save and improve lives.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.