“Why the hell are we here today?”

Chris O’Neill, Evernote’s CEO, is addressing an audience made up of the company’s employees in a tent pitched on the roof of its parking garage just off Highway 101 in Redwood City, California. With cars and planes buzzing outside, he plunks his bottle of Hint water on the edge of the stage and proceeds to answer his own cheekily phrased question. Evernote has assembled to mark its 10th anniversary–“an opportunity for us to pause and reflect about how far we’ve come, but also to look at the road ahead,” he says. That road includes the first major evolution of the company’s brand in years, which the staffers get to see on this day in late June, well before its public rollout.

If it feels like Evernote has been around for more than a decade . . . well, that’s because it has been. The company cheerfully concedes that what it’s calling its 10th anniversary is actually the 10th anniversary of the iPhone version of the note-taking app, which debuted in July 2008, on the day the App Store opened for business. A defining moment for sure, but not the origin story of the business. I knew that because I’d first written about EverNote (as it was originally known) in September 2004, after being impressed by a beta version at the DemoMobile conference in San Diego.

Back then, Evernote was a piece of Windows software, and the company’s founder, Russian-American computer scientist Stepan Pachikov, was the guy who walked me through what it could do. By the time it arrived on the iPhone, he’d already stepped down as CEO. But as the company commemorates its self-defined 10th birthday, it’s also re-embracing Pachikov as its founding visionary.

With 225 million registered users spanning nearly every country on Earth, Evernote has indeed come a long way since Pachikov created the app, mostly to please himself. But his initial concept of a digital storehouse for all the information humans tend to forget—which grew only richer as he realized that other people wanted it, too—has had staying power. It’s propelled the company down the sometimes twisty path it’s followed through its history, and shows every sign of being powerful enough to help take Evernote where O’Neill thinks it should go next.

So how old is Evernote? You can make a case that it actually turned 18 early this year. In February 2000, Pachikov registered Evernote.com and put up a placeholder page with little more than a cryptic mission statement (“Computers are powerful enough today to avoid a situation when a user feels himself as an idiot”) and a founding date of Leap Day. Today, he explains that when he started thinking about note-taking, he was inspired by Apple’s Newton handheld computer. The pioneering-but-unsuccessful gadget had shipped in 1993 with handwriting-recognition technology provided by ParaGraph, a company Pachikov cofounded in Russia; the collaboration prompted his relocation to the U.S.

Once on board, Talnykin whipped up a prototype of a Windows notes app based on the endless-tape principle. Pachikov had initially conceived of the software purely to please himself, but his wife Svetlana was equally enthusiastic about Talnykin’s rough draft. “She so liked it that it encouraged us to continue working on the project,” he says.

The vision for Evernote that Pachikov developed was ambitious, especially given the apparently mundane nature of the category it was entering. For decades, innumerable pieces of software had helped people take notes. Most, however, were basic tools for short-term storage of snippets of information—the digital equivalent of Post-it Notes. Microsoft’s OneNote, which debuted in 2003, was meatier. But as part of Office, it was pretty much just a specialized word processor.

Pachikov increasingly saw his software as being less about any single note you might store than the aggregate power of having everything you ever wanted to remember at your fingertips, now and forever. A feature in the original version called “Time Band” let you jump back to any given month, day, and year; Pachikov initially thought that might be as useful as full-text searching, which Evernote also offered.

Though Evernote started out on Windows computers, working on all the devices in a user’s life was part of the vision from early on: The product’s first press release referenced the ability to “wirelessly sync over the internet between home PCs, office PCs, smartphones, and PDAs,” a promise that ran a little ahead of the initial reality. In this pre-iPhone time, Pachikov owned an early smartphone manufactured by HTC, and using it gave him the sense that “the smartphone eventually would be an extension of the human brain,” he remembers. Such a device, once it existed, would be the ideal home for Evernote, he felt.

As a Windows app, Evernote sold for $35, got good reviews, and garnered a cult following of about 80,000 users, which wasn’t enough to thrive. “I never pretended I was a good businessman,” shrugs Pachikov. He decided to hire a replacement for himself as CEO. After his initial choice lasted less than a year in the position, he found Phil Libin, a Leningrad-born, Boston-based entrepreneur who had started two companies involved in technical plumbing such as identity management and was looking for something more spiritually fulfilling in his next challenge. “I fell in love,” says Pachikov. “In 30 minutes, I wanted him to run the company.”

Libin joined as CEO in 2007 and didn’t turn the company into an instant phenom; at one point, he was getting ready to shut it down when a reprieve landed in his inbox in the form of an unsolicited investment offer from an Evernote enthusiast in Sweden. But the iPhone—once it began to support third-party apps—was the sort of epoch-shifting device that Pachikov had fantasized about a couple of years earlier, and Libin’s Evernote was intrepid enough to seize the opportunity. It also rearchitected the app to store notes in the cloud, helping to make Evernote more of a permanent repository even though Pachikov had originally believed that sharing between devices should be accomplished through peer-to-peer synchronization in the interest of privacy. “I was wrong,” he now admits.

Libin’s sense of showmanship was as strong as his timing. According to venture capitalist Roelof Botha of Sequoia, which invested a total of $70 million in Evernote in 2010 and 2011, “Phil is a Pied Piper. People would follow him, and he had an ability to whip up a frenzy and excitement around the company that was really amazing.” The app that had once seemingly maxed out at 80,000 users later reached 150 million people—most of whom used it for free, with the most serious adherents paying for premium features. Lots of Silicon Valley companies host lavish conferences for developers; Evernote was unusual in welcoming people who just plain loved its product to its Trunk extravaganzas.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=eZG0w8V7Ud4&t=789s

Pachikov’s founding vision of letting people safely store a lifetime’s worth of vital information for easy retrieval remained at the heart of the business. But at the same time, Libin contended that Evernote wasn’t by definition a technology company. Working with a variety of partners, it began selling backpacks and courier bags—nice ones!—as well as Fujitsu scanners and Moleskine notebooks that integrated with its app. In 2013, when I wrote about the company for Time, Libin told me that the overarching goal was to be a sort of Nike of the mind, “the most important brand for people who care about their lives, who want to build smarter, more productive lives.”

Without Libin’s contributions, Evernote might be remembered—or not remembered—as a once-promising Windows application that failed to make it into the mobile age. Pachikov is more than happy to share credit for the company’s very existence: Libin, he says, “really deserved to have the title of cofounder even though he joined five years later.”

By 2015, Evernote seemed to be well down the road to an IPO. Libin, who had always said he had no intention of being Evernote’s last CEO and now acknowledged that he wasn’t passionate about taking the company public, did something roughly comparable to what Pachikov had done eight years earlier: He replaced himself. The new CEO was O’Neill, an Ontario native who’d spent a decade at Google in various positions, including running business operations in Canada and managing the Google Glass project. (Libin stayed on as executive chairman but left 14 months later; today, he runs All Turtles, an AI “startup studio.”)

When O’Neill assumed leadership of Evernote, “I frankly thought the company had lost the plot a little bit, and felt that I could reconnect it to its founding roots,” he says. After a 45-day listening tour, he concluded that Evernote needed, above all, to rededicate itself to making its namesake product robust and easy to use.

Through focus and financial disclipline, “Chris eventually saved the company,” believes Pachikov. O’Neill declared that Evernote, which had raised around $300 million over the years, had no plans to seek additional investment and would henceforth strive for self-sufficiency. In February 2017, in a blog post evocatively titled “Turning an Elephant,” he said that the business was now cash-flow positive.

“It’s great when a company starts to raise non-dilutive capital every day, which is called revenue,” says Sequoia’s Botha. “And when you get enough of that revenue, you control your own destiny and you’re not at the mercy of capital markets and ongoing financing. That’s exactly what Chris has done for the company.” The company declines to comment on any current plans it may have to go public; it did, however, recently spin out its operations in China in part to prepare for an eventual IPO for that business.

Libin had been fond of talking about Evernote’s 100-year-plan and waxing futuristic about topics such as what the app might look like once augmented-reality glasses were commonplace. O’Neill, by contrast, is more at home talking about achievable, shorter-term goals. Many involve making Evernote into a more potent corporate tool, thereby increasing the number of companies that pay to provide their employees with Evernote Business, the highest-end incarnation of the service. That’s not a new imperative—back in Libin’s day, Evernote introduced a service called Work Chat, which failed to pose a threat to the likes of Slack—but now over 20,000 organizations are customers.

Increasing that figure will involve yet another fresh spin on the company’s original goals. When O’Neill came to Evernote, “‘Remember everything’ was for all intents and purposes the mission,” he says. “An extension of the human brain, a place to store things and then retrieve them in the moments that mattered. That’s all true. But what we’re doing is extending that to turning those ideas into action. So rather than just capturing them, you’re actually doing something.”

A real-time collaboration tool called Evernote Spaces, added to Evernote Business earlier this year, hints at this direction. For a sense of where the company might take it next, O’Neill says, consider how Evernote might make itself more useful as a meeting tool. “Everyone hates meetings, and most of them suck,” he says. “They suck because they don’t have an agenda, the wrong people are in the room, there’s no follow-through. You can go on and on and on. Thirty-one percent of our active users use us for meetings. We’re leaning into that to figure out how we either eliminate the damn meeting or make them 10 times better.”

In the O’Neill era, Evernote has mostly stayed out of the news. The major exceptions have been kerfuffles over a price hike and changes to its privacy policy. Then there was the time that Business Insider published a story whose headline pronounced Evernote to be “the first dead unicorn.” (In the grand tradition of hot takes, the piece didn’t actually argue that Evernote was dead, but rather that it was failing to live up to expectations.)

Now, three years into his tenure and with some of the heavy lifting completed, O’Neill is ready for Evernote to call attention to itself again. “I’m spending some money on marketing for the first time in a long time, if ever,” he says. The brand refresh, nine months in the making, is the most tangible result yet of that investment.

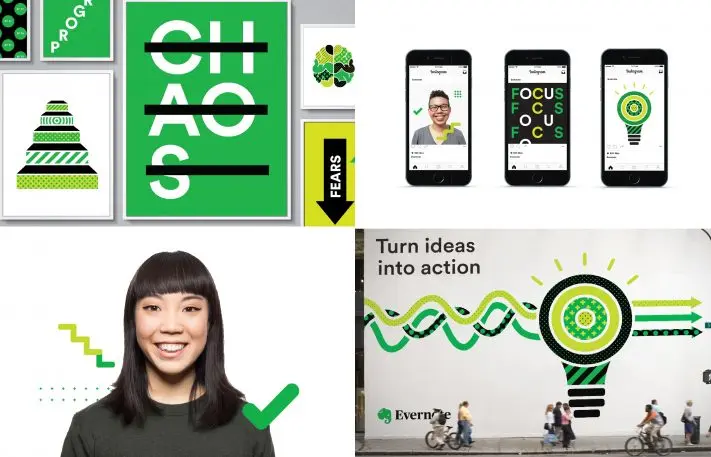

The company went through standard exercises such as describing its brand in flattering adjectives, concluding that Evernote is optimistic, clever, confident, and clear. Eventually, “we locked onto this idea of focus being the thing that touches everything we do,” explains executive creative director Jonathan Woytek. “We’re not just productivity, we’re not just organization. We’re not just hopes and dreams and journals and memories. We’re all of that.” Adds DesignStudio creative Director Ty Whittington, “Overcoming life’s complexities so that you can focus on what matters most was the essence of the new brand strategy. This idea of progress.”

Evernote had also embraced green as its corporate color after realizing that red and blue tended to make any elephant look like a Republican-party symbol. Unlike those colors, green was not widely used in software iconography, giving Evernote a chance to own it. Even if users didn’t know the backstory behind the elements, Mads’s silhouetted head on a green background made for an icon that was easy to spot in a sea of apps on a smartphone.

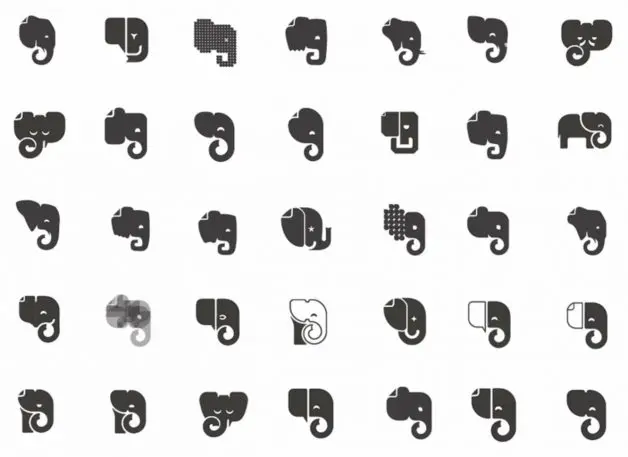

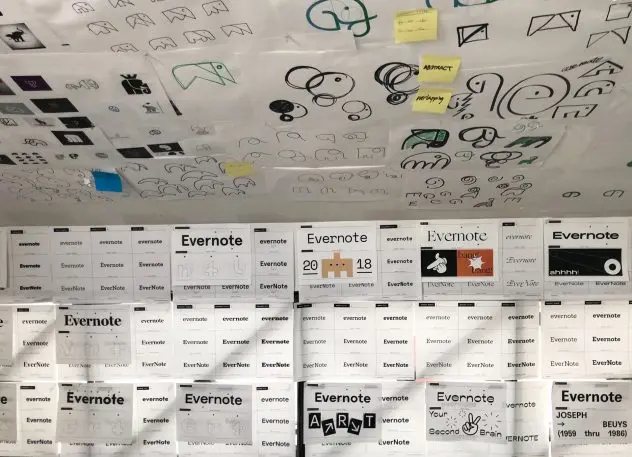

When the 2018 rebranding effort came around, however, Evernote gave DesignStudio free reign to fool around with what had come before or abandon it altogether. “We asked them to make us very, very uncomfortable and push us out of our comfort zone,” says Woytek. The evidence remains on the walls of a “war room” at DesignStudio’s San Francisco office, where printouts run up to the ceiling and overflow out the door into adjoining space.

These concepts show elephants that are more realistic than Mads and ones that are barely recognizable as elephants. In the interest of conveying a confident spirit, one pachyderm bounds up a staircase; another soars like Superman; a third encircles the stars in the sky with its trunk. DesignStudio also experimented with depicting the concept of forward progress in ways that don’t involve an elephant at all, such as through a spiral design.

As for the Evernote wordmark, the company toyed with an array of possibilities, even investigating how it would look as “EverNote,” Pachikov’s original styling. In the end, Evernote stayed Evernote, and is now rendered in a tweaked version of a typeface called Publico. By rendering the company’s name in upper- and lowercase with serifs, DesignStudio means to subtly convey the power of ideas as expressed in prose, but it’s also a contrarian move in an age when many tech companies have lookalike sans-serif logos, which emphasize simplicity over personality. It’s “very editorial, and a lot of Evernote users are on the intellectual side or perhaps read a lot,” says Whittington. “But it signaled some change and stood out from the sea of similar typography that’s out there.”

Along with Mads 2.0 and the new wordmark, DesignStudio provided Evernote with a toolkit of visual elements to utilize in marketing and other materials. They include two shades of green, a sans-serif typeface called Soleil, and a variety of upbeat-looking shapes—a star, a check mark, an up arrow—which the company can mix and match and meld with photography. They were all designed to look good on anything from a dinky smartphone screen to an oversized outdoor advertising poster—and yes, Evernote plans to reintroduce itself through an upcoming brand advertising campaign.

Besides DesignStudio’s work, Evernote’s new way of presenting itself to the world includes another component: Stepan Pachikov. “When we started to kick off the brand work, tapping into that legacy was profound—the reasons why he invented Evernote,” says Francie Strong, Evernote’s VP of brand and communications. “Brands want stories like this all the time, and I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, we actually have this amazing thing.’ I would talk about Stepan all the time, and nobody knew who he was. Everyone knew Phil.”

Last year, Evernote published a lengthy profile of Pachikov on Medium. The piece celebrated his prescience—along with handwriting recognition, ParaGraph was doing VR in the 1990s—and soberly discussed the fact that he has Parkinson’s disease, an ailment that can affect the memory. Pachikov wasn’t present in person for the “10th anniversary” festivities, but a sizable chunk of the onstage presentation paid tribute to him. That included the premiere of an Evernote-commissioned mini-documentary on Pachikov by noted photographer and filmmaker Mark Seliger, who bonded with his subject over their shared love of photography and says he found him “very engaging, very loving, concerned, empathetic.”

Pachikov’s current relationship with Evernote isn’t merely ceremonial. A longtime resident of New York City, he’s been on the company’s board all along and visits its Silicon Valley headquarters for quarterly meetings. Though he praises both Libin and O’Neill’s strikingly different stewardships of his brainchild—and stresses that a business can’t have competing visionaries—he adds that he’s still full of ideas for ways to make Evernote better, and has often felt underutilized.

“I told Chris that if it wasn’t for Parkinson’s, I would insist that he hire me as a chief product architect,” says the 68-year-old founder wistfully. For his part, O’Neill declares his “incredible respect” for Pachikov, whom he confirms is “never happy” with Evernote as a product experience.

Even if Pachikov craves more hands-on involvement, Evernote’s staffers prize the face time they get with him. “He and I talk about all the medical advances that we’re making,” recounts chief growth and marketing officer Andrew Malcolm. “I lose an arm, I can get a prosthetic. I can even transplant my heart and my kidney. But you can’t change your brain. Software is ultimately going to have to be that replacement for your brain. That’s a future that I don’t think a lot of people sit down and start to contemplate. But it’s profound when you take a moment to think about it. And for a bunch of us who really nerd out about life, we love that idea.”

For Evernote, in other words, moments spent with its creator aren’t a simple act of nostalgia. Instead, they’re an invigorating reminder that the potential of its mission is boundless—and that the company, whatever its actual age, has only begun to explore it.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.