If you order a taco or an Amazon Echo Dot in the U.S. in the coming years, it will still be delivered by a human, not a drone. Tough regulations will limit airborne deliveries to publicity stunts and pilot projects for some time.

But business is growing for about a dozen less-flashy jobs that small and medium-sized sensor-equipped drones can do, such as inspecting cell-phone towers or wind turbines for damage, surveying progress at construction or mining sites, and assessing storm damage for insurance claims. Hollywood and the independent film industry also love drone cameras as a far more accessible alternative to helicopters.

“No matter what lens you look through, film/photo/video is the #1 use for drones,” writes Skylogic Research, based on a survey of 2,666 people in 60 industries. Industry analysts are ecstatic, with the global market expected to reach $13 billion by 2020, according to Goldman Sachs, likely led by uses in construction and agriculture.

Entrepreneurs are rushing in, according to Skylogic, with most setting up shop in the past year, but few are making much money. About half are part-timers, and only 15% make more than $50,000 per year. “The predictions of big economic growth and job creation have not come true, at least not yet,” say the researchers. Most struggling operators in the U.S. blame strict regulations and a sluggish government permitting process.

Demonstrating government’s penchant for long titles, the service is called Low Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability, abbreviated LAANC and pronounced “lance.” It replaces the U.S.’s heavily bureaucratic permitting processes for managing flight safety around airports with a visual, cloud-based point-and-click map with a grid overlay.

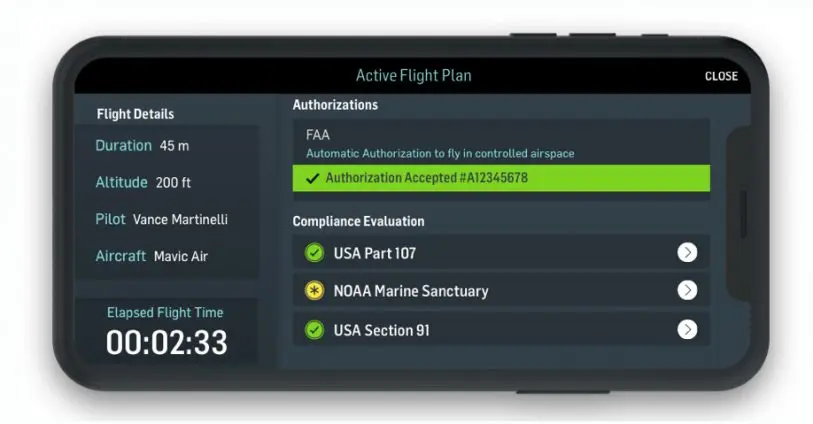

Segments near the runway have a flight altitude limit of zero–verboten. Further out, the allowance grows higher, up to the federal limit for drones of 400 feet. Using LAANC-connected mobile apps, drone pilots select areas they want to fly in and get a yes or no back in near real time. LAANC can even be connected to the remote-control apps that pilots use to fly their drones, allowing the apps to prevent pilots from straying too high or outside the permitted areas.

On April 30, the Federal Aviation Administration switched on LAANC in a region including Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and Louisiana. Each month, it comes to another six regions, until about 500 airports across the country are included. Wave three of the rollout, on June 21, includes California and Hawaii. All of the nation’s significant public airports are scheduled to be included in the program by September 13.

“Over 2,000 square miles of airspace that was previously unavailable to commercial operators is now going to be available,” says Joshua Ziering, cofounder of Kittyhawk, maker of an eponymous mobile and web-based software suite for managing drones.

Putting drones where customers are

Ziering’s estimate may not sound like much in a country of about 3.8 million square miles. But location matters, as any realtor can tell you–especially if they’re among the growing number of realtors using drone video to market their properties.

“It’s airspace near airports, which includes most of the major urban areas in America and some of the most valuable areas to fly a drone,” says Bill Goodwin, chief counsel and policy head for AirMap, a maker of drone mapping and planning software.

LAANC rolls out between April 30 and September 13. [Animation: courtesy of FAA]Drone businesses have been essentially limited to areas far from airports (and most people), in what’s called Class G airspace. The rules out there, described in a regulation called Part 107, are straightforward. For example: Drones can’t fly above 400 feet, at night, or beyond sight of the operator (although some waivers are possible).

Airspace closer to airports–classes B, C, D, and E–requires prior authorization, which, without LAANC, takes an average of 100 days, says the FAA. Drone hobbyists, however, only have to call the airport to provide a heads up–a sore point for commercial pilots.

Related: These Medical Delivery Drones Could Soon Be Supplying U.S. Hospitals

“[It] took so long to get [an authorization] . . . we would just say ‘we can’t fly there,'” says Dan Burton, founder of DroneBase, a company that matches licensed drone operators with clients who need their services. (Burton gamely accepts “the Uber of drones” as a shorthand description.) “So anything Class G is probably yes. Anything restricted, we just say ‘no’ right now.”

Burton reckons that has cost him 30% to 35% of all jobs. DroneBase may follow the rules, but Harrison Wolf, head of the drone program at the World Economic Forum’s San Francisco office, believes that many entrepreneurs simply fly without permission.

He asked me not to name clients, but they include very recognizable media, energy, and insurance companies, as well as government agencies. Kittyhawk (which is unrelated to the flying-car startup Kitty Hawk) supports police departments, for instance, which use drones to surveil a suspect’s property before sending in a SWAT team–something that can’t wait months for a permit.

Other restrictions, like the line-of-sight rule, which requires operators to maintain an unaided visual of their drones, will still hold back drone deliveries. (The FAA recently announced 10 drone pilot programs, including deliveries, meant to help it devise business-friendly regulations.) But with LAANC in place, the remaining restrictions won’t hurt camera- and sensor-based businesses much, says Burton.

Related: In a first, NASA’s Predator drone flew solo in commercial airspace

“Drones as a platform . . . are really best in the world at what I would call property-level data capture–I think about under 800 acres,” he says, keeping in mind most small drones’ roughly 20-minute battery lives. “Any property, any worksite, any kind of asset like infrastructure where you need that detailed view.”

Getting to drone-filled skies

LAANC is just the beginning. The U.S. government is planning for way more crowded skies, with not only camera and delivery drones but also flying taxis from Airbus, Uber, and others. That requires more-sophisticated technology, with a more-confusing name: Unmanned Aircraft System Traffic Management–scrunched down to the abbreviation UTM.

The altitude restrictions on grids in the LAANC map ensure that drones (if they follow the rules) won’t collide with planes. But for now at least, it’s up to the drone operators to avoid crashing into each other.

Developed by NASA with help from the FAA, UTM will parcel out airspace in narrow pathways that allow many drones and air taxis–possibly even traditional helicopters and planes–to fly close together without colliding. These might be fully autonomous vehicles or a mix of autonomous and piloted craft, someday sharing a increasingly busy sky.

This won’t happen in a year or two, but big players want it in less than a decade. Airbus aims to have its autonomous flying cab, Vahana, ready for business by 2022. Uber and its partners, such as aircraft makers Bell, Boeing, and Embraer, want to start commercial air taxi service by 2023.

“We really want to imagine that world where most flights are drone flights, most commercial flights are commercial drone flights,” says Burton of DroneBase. “And I think that’s absolutely possible.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.