Mark Zuckerberg has yet to speak publicly about last week’s news that a researcher turned 270,000 responses to a Facebook quiz into profiles of 50 million Facebook users, which he turned over to Trump-affiliated political research group Cambridge Analytica. Zuckerberg (and COO Sheryl Sandberg) didn’t even attend a Tuesday employee town hall about the matter, although he will reportedly address the issue within the next 24 hours.

Related: From Denial To Panic: A Timeline Of Facebook’s Evolution On Russia

While the rest of us wait for Zuckerberg to say something, it’s worth revisiting some past Facebook controversies and how he responded to them. Let’s start at the beginning. Wait, let’s start even a little before that . . .

November 2003: “This Is Not How I Meant For Things To Go”

Three months before Zuckerberg launches TheFacebook.com from his Harvard dorm, he creates Facemash, a Hot or Not-esque site that (briefly) lets his fellow students rate each other’s looks, using photos Zuckerberg has downloaded in bulk from several on-campus sources. A half hour after it becomes a phenomenon–and subject of outrage–he shuts it down. “I don’t see how it can go back online,” Zuckerberg tells the Harvard Crimson. “Issues about violating people’s privacy don’t seem to be surmountable. The primary concern is hurting people’s feelings. I’m not willing to risk insulting anyone.” In a letter to irate classmates, Zuckerberg gives his first apology to make the news: “I hope you understand, this is not how I meant for things to go, and I apologize for any harm done as a result of my neglect to consider how quickly the site would spread and its consequences thereafter . . . I definitely see how my intentions could be seen in the wrong light.” Zuckerberg is called before Harvard’s administrative board for violations of both privacy and copyright, but survives–and gets to work on a social network for his fellow Harvardians.

September 2006: “Calm Down. Breathe. We Hear You”

Shortly before it ends its student-only restriction and opens up to everyone over the age of 13, Facebook starts aggregating activity from each member’s friends into a new feature called the News Feed. Though it soon becomes the primary way to consume Facebook, some users find it creepy or simply overwhelming. In a blog post titled “Calm down. Breathe. We hear you,” Zuckerberg informs the unhappy campers that they’re worked up over a work in progress that doesn’t make the service less private. After a few days’ reflection, however, he concedes that “we really messed this one up.” He goes on to insist that Facebook has always been about giving people control over their own information: “Somehow we missed this point with News Feed and Mini-Feed and we didn’t build in the proper privacy controls right away. This was a big mistake on our part, and I’m sorry for it.”

December 2007: “People Need To Be Able To Explicitly Choose What They Share”

As Facebook begins to develop a strategy to monetize its 50 million users, it introduces Beacon, a technology that automatically tells your friends about your activities at third-party sites such as Epicurious, Fandango, Overstock, and Travelocity. It does so without getting permission or allowing permanent opt-out, prompting anger and confusion akin to the 2006 News Feed dustup. “We’ve made a lot of mistakes building this feature, but we’ve made even more with how we’ve handled them,” Zuckerberg admits in a blog post explaining post-launch tweaks to Beacon. “We simply did a bad job with this release, and I apologize for it.” The feature is the subject of class-action suits and disappears altogether after less than two years.

May 2010: “We Will Keep Building, We Will Keep Listening”

Facebook privacy violations are again in the news as the Wall Street Journal‘s Emily Steel and Jessica Vascellaro report that the company (and other social networks such as MySpace) divulge unique user IDs to advertisers, which can be used to track consumers. As part of Facebook’s cleanup effort, Zuckerberg publishes a Washington Post op-ed allowing that the company’s privacy options “just missed the mark” but also underlining that the company’s goal is to make the world more open. “Facebook has evolved from a simple dorm-room project to a global social network connecting millions of people,” he writes. “We will keep building, we will keep listening, and we will continue to have a dialogue with everyone who cares enough about Facebook to share their ideas.”

September 2010: “I Think I’ve Grown And Learned A Lot”

Months after Silicon Valley Insider publishes old instant messages in which Zuckerberg makes incendiary remarks such as calling the earliest Facebook members “dumb fucks” for trusting him with their information, he issues a mea-sorta-culpa during an interview with the New Yorker’s Jose Antonio Vargas. Zuckerberg says that he “absolutely” regrets the six-year-old exchanges but shouldn’t be judged by them: “If you’re going to go on to build a service that is influential and that a lot of people rely on, then you need to be mature, right? I think I’ve grown and learned a lot.”

For about six years, Facebook does a surprisingly adept job of sidestepping major controversies, giving Zuckerberg less reason to tell anyone he’s sorry about anything. And then . . .

November 2016: “The Idea That Fake News On Facebook . . . Influenced The Election In Any Way Is A Pretty Crazy Idea”

At a conference days after the U.S. presidential election, Zuckerberg dismisses concerns about Facebook’s role in its outcome: “Personally, I think the idea that fake news on Facebook, of which it’s a very small amount of the content, influenced the election in any way is a pretty crazy idea.” He adds that the theory that voters were swayed by hoaxes assumes that Trump voters were unsophisticated consumers of information, which he doesn’t buy. “People are smart and they understand what’s important to them,” he argues.

February 2017: “I Often Agree With Those Criticizing Us”

Three months after the election, Zuckerberg publishes a 5,000-word manifesto that never mentions Donald Trump by name but does allow that Facebook has been overwhelmed by the task of policing its content on a variety of fronts. “We’ve seen this in misclassifying hate speech in political debates in both directions–taking down accounts and content that should be left up and leaving up content that was hateful and should be taken down,” he writes. “Both the number of issues and their cultural importance has increased recently.” Zuckerberg adds: “This has been painful for me because I often agree with those criticizing us that we’re making mistakes,” prompting CNBC’s Christine Clifford to declare that his willingness to expose his vulnerability makes him a strong leader.

September 2017: “This Is Too Important An Issue To Be Dismissive”

After President Trump says that Facebook has always been out to get him, Zuckerberg says that the fact that both the president and his critics are mad at Facebook shows that the service is a forum for free expression. He points out ways in which Facebook’s impact on the 2016 campaign was positive–such as its get-out-the-vote effort–and says that the media has mischaracterized the company’s role. Along the way, though, he backpedals on his initial comments about the possibility that misinformation on Facebook influenced the election results: “Calling that crazy was dismissive and I regret it. This is too important an issue to be dismissive.”

Also In September 2017: “I Ask For Forgiveness And I Will Work To Do Better”

On the last day of Yom Kippur, Zuckerberg atones for his own failings in a Facebook post but also mentions unspecified instances of others abusing Facebook for divisive means: “For those I hurt this year, I ask forgiveness and I will try to be better. For the ways my work was used to divide people rather than bring us together, I ask for forgiveness and I will work to do better.”

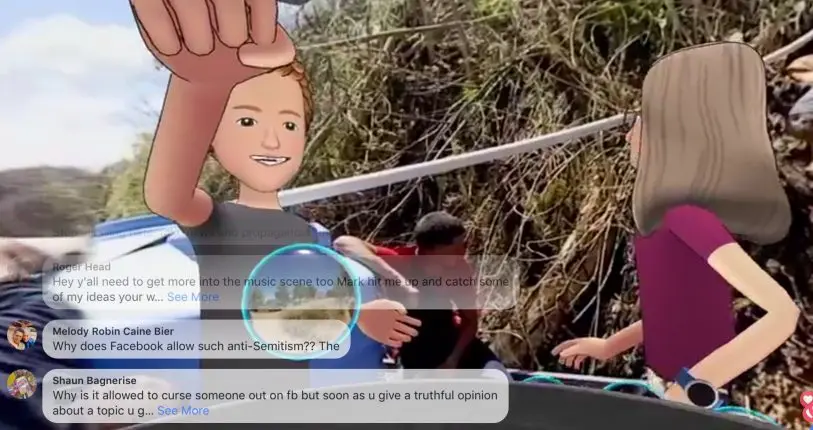

October 2017: “I’m Sorry To Anyone This Offended”

After Puerto Rico is devastated by Hurricane Maria, Zuckberg broadcasts a video using Facebook’s Spaces VR app in which cartoon versions of himself and a colleague teleport to witness the damage. After some commenters criticize the effort as insensitive or opportunistic, he chimes in via a comment of his own to say that his goal had been to show VR’s potential for increasing human empathy. “Reading some of the comments, I realize this wasn’t clear, and I’m sorry to anyone this offended,” he writes.

January 2018: “Facebook Has A Lot Of Work To Do”

Each January, Zuckerberg announces a goal for the year ahead, typically involving a personal goal such as eating only meat from animals he personally kills or reading a new book every other week. For 2018, however, his objective is all about pressing problems at his day job. “The world feels anxious and divided, and Facebook has a lot of work to do–whether it’s protecting our community from abuse and hate, defending against the interference by nation states, or making sure that time spent on Facebook is well spent,” he posts on his wall. “My personal challenge for 2018 is to focus on fixing these important issues. We won’t prevent all mistakes or abuse, but we currently make too many errors enforcing our policies and preventing misuse of our tools. If we’re successful this year then we’ll end 2018 on a much better trajectory.”

Looking over Zuckerberg’s past reactions to Facebook catastrophes, kerfuffles, and minor embarassments shows that he’s gotten better at sounding humble and avoiding the temptation to tell people that the fact they don’t like something is a sign they don’t understand it. It also suggests that when easy fixes will allay concerns, he’s pretty good at making them. But the Cambridge Analytica crisis strikes at the heart of Facebook’s data-mining business model and involves factors not entirely under his control, limiting the value of his past experience at damage control. And with the company’s stock tanking, legislators demanding answers, and class-action hell on the horizon, the stakes have never been higher.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.