Victoria Kotongan grew up in the Native Village of Unalakleet, Alaska, where she still lives and hunts grouse for subsistence. A few years ago, she was cleaning a couple of the birds she shot, and noticed all of them had worms coming out of the breast meat. Had she found a worm in just one of the birds, she might not have worried, but this was all six of them, and she’d never seen this disease before.

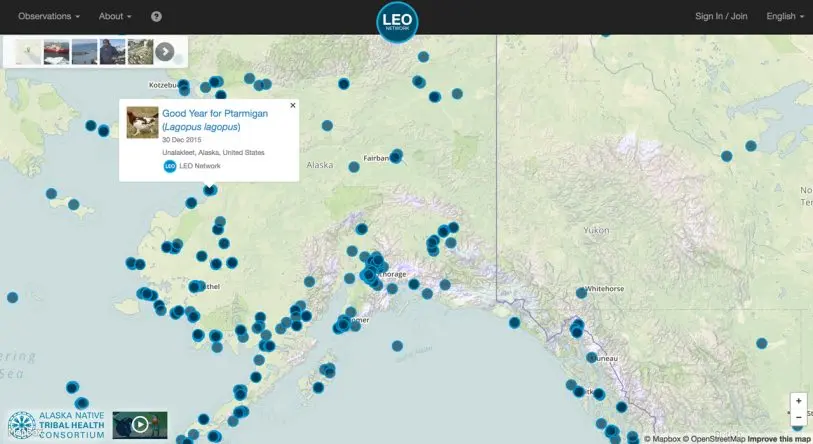

Kotongan is a member the Local Environmental Observer (LEO) Network–a digital citizen science platform that connects people, like Kotongan, with deep traditional or indigenous local knowledge with scientists to identify and document signs of environmental change. The nearly 1,678 members of the network are concentrated in North America and include tribal elders, scientist, fishermen, and hunters. The 728 unusual natural occurrences tracked on the LEO Network’s interactive map since 2012 cluster in the U.S., but a handful have been reported in Africa, Australia, and Europe; they range from low water at the banks of the Klamath River in northern California to southern flying squirrel species migrating north in Ontario.

“The thing is, with climate change, everything is changing,” says Mike Brubaker, who founded the LEO Network in 2012, through the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC), a health-service nonprofit for which he serves as the director of community environment and safety. “And if people are immersed in their local environments, they’re going to be really good at noticing when something’s different.”

Brubaker grew up in Alaska, and over the course of his life he’s watched the vegetation transform on the Chugach Mountains in the southern part of the state; once Brubaker started at the ANTHC in 2008, he began to travel to more remote parts of the state, where he spoke with native communities and subsistence farmers who “have such amazing familiarity with the landscape and the weather, that they were able to make really very subtle observations about the kinds of changes that were occurring,” Brubaker says. “We realized that this kind of knowledge was crucial as we try to make these connections between the changing climate and changing environment, and the effect it has on people and populations.”

“The key question is: Are you noticing environmental change based on your knowledge?” Brubaker says. “If so, then it’s probably significant and appropriate to share.” As the LEO Network grows, Brubaker envisions collaborations between observant citizens and scientific researchers informing the debate around the environmental effects of climate change, and connecting that debate more strongly with the people whose livelihoods are affected by the changing landscape. Tom Okey, a Pew Marine Fellow under the Pew Charitable Trusts’ conservation program, told the British Columbia-based Times Unionist that the local knowledge aggregated through the LEO Network could fill some of the gaps that more mainstream systems fail to catch when seeking out signs of environmental change.

While the most active people on the LEO Network either have a science background or have lived close to the land, anybody with an interest in citizen science, or following the changes tracked on the platform’s interactive map, can sign up. “I hope people recognize the value of signing up just to be a part of the discussion,” Brubaker says. “Part of the solution for dealing with this rapid change is creating a community of people with this knowledge to share.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.