One year ago, Chanice St. Louis was working part-time as a barista, struggling to pay bills, and trying to figure out how to get back into a community college in Brooklyn after her work schedule and a family illness ruined her grades. Now she’s a newly minted software developer–and she’ll be contributing part of her salary back to the free program that taught her to code.

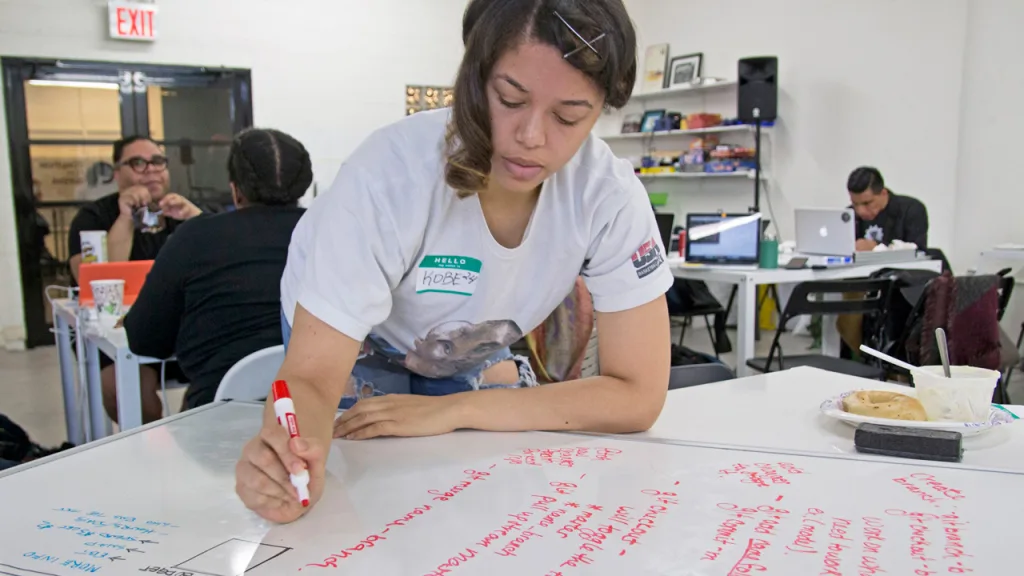

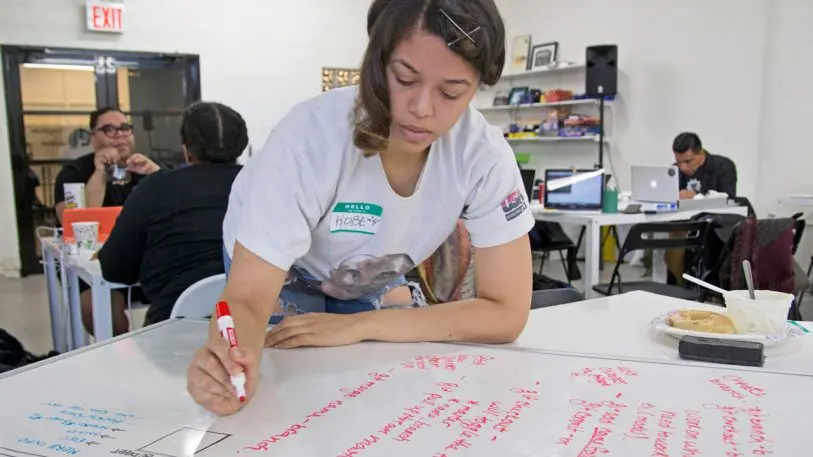

St. Louis is part of the 2017 class of C4Q, a nonprofit that recruits New Yorkers from low-income, underserved communities, teaches them programming over an intensive 10-month course, and then helps them land jobs at companies like Pinterest and Kickstarter.

The organization’s first class graduated in 2013, but this year it tried something new: Students committed to donate a percentage of their salaries after graduation back to the program if they get a job. This contribution, at 12% of someone’s salary, lasts for two years. “It’s not a loan, and it’s not a debt,” says Hsu. “We purposely didn’t want to do that. There’s so many terrible experiences where people are just saddled with debt and loans.”

“Our vision is: How do we have this scale?” says Hsu. Out of 1,200 applicants last year, the program could only accept 100 people. Around 1.7 million New Yorkers are living in poverty; across the United States, that number is more than 40 million. “Tech’s not a solution for everything,” he says. “But we do think this can meet a huge need.”

“That kind of lured me to go into this program, still not knowing what computer programming was, not knowing that there were so many languages–having zero exposure, basically,” she says.

Like other applicants, she had to pass an interview stage, and then come in for a three-day series of workshops and take tests to assess her existing knowledge. She struggled with the tests and assumed she wouldn’t be accepted, but the organization recognized that she had the qualities they seek in applicants: intelligence, potential, and grit. (As an example of grit, St. Louis had filed seven appeals to administrative offices at her former community college in the process of trying to get re-accepted, battling a bureaucracy that informed her of the existence of an appeals office only on her seventh appeal). She was in.

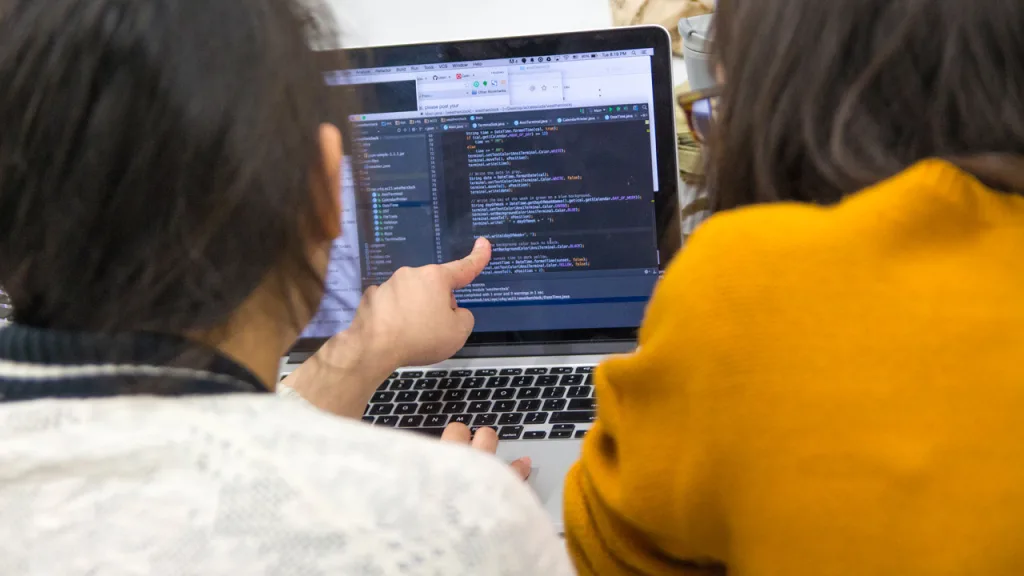

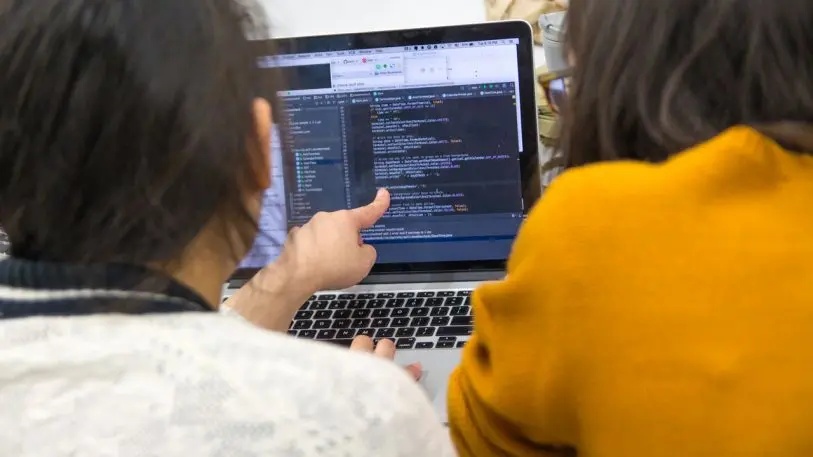

The program teaches coding skills, but also basics about the industry, and introduces students to a network in the tech world. “It’s not just learning to code,” says Hsu. “That’s just a baseline. Obviously, there’s a proliferation of three-month bootcamps, they’re amazing, but I think for our audience–you don’t have advantages and privileges to make that successful. A lot of that is not the base coding skills. If it was just about learning to code, online courses and MOOCs would be the solution for everything.”

The organization offers a night and weekend course along with one that meets on weekdays. St. Louis attended Monday through Friday, and initially tried to keep working on weekends, though she had to stop after three months, relying on the fact that she lives with her mother to keep going financially. (C4Q hopes to be able to provide financial support in the future for students, many of whom struggle to keep working while in the program.)

Students in the current class, which officially graduates on June 12, have gotten jobs at companies that include Uber and LinkedIn. St. Louis took a job as a junior software engineer intern at a startup called Propel that makes an app for families on food stamps to keep track of their food budgets and save money with deals from grocery stores. “My family’s been on food stamps myself,” she says. “So I can give a better insight to how they can implement these features to optimize their app.”

A handful of past graduates have started their own companies. Moawia Eldeeb, whose family immigrated from Egypt to get treatment for his brother’s rare illness–and who dropped out of school in the sixth grade to help support his family, later returning–went through the program and eventually launched a company called SmartSpot that made it into Y Combinator and got venture funding.

As the program expands, Hsu hopes that others will also launch startups. “We believe people from every economic background should have the opportunity to not only learn to code and get a great job in tech, but also create companies and become entrepreneurs,” he says. “Not that everyone’s meant to be an entrepreneur, but everyone should have the opportunity to do so.”

The next step is to prove that the new financial model works, and helping launch something similar in other communities. “Tech has created this amazing wealth, in San Francisco, New York, and elsewhere, but it’s also created this tremendous inequality that we’re seeing,” he says. “We want to transform technology–instead of creating this inequality, becoming the driver for opportunity and equity. Not just here in New York, but across the country.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.