The first language you learn as a baby “locks in” certain patterns in your brain and affects how you will learn other languages in future. Even if you forget that first language, it will continue to influence how you hear the sounds from other languages you may learn.

Researchers from McGill University and the Montreal Neurological Institute found that different parts of the brain light up when hearing your own original mother tongue, compared with words from a subsequently learned language.

The study used three groups of adolescents and tested them using nonsense French words. One group was French and only spoke French. The second group comprised adopted Chinese babies who had stopped speaking Chinese and now only spoke French. The third group was bilingual in French and Chinese. The youngsters listened to the nonsense French words while inside a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner.

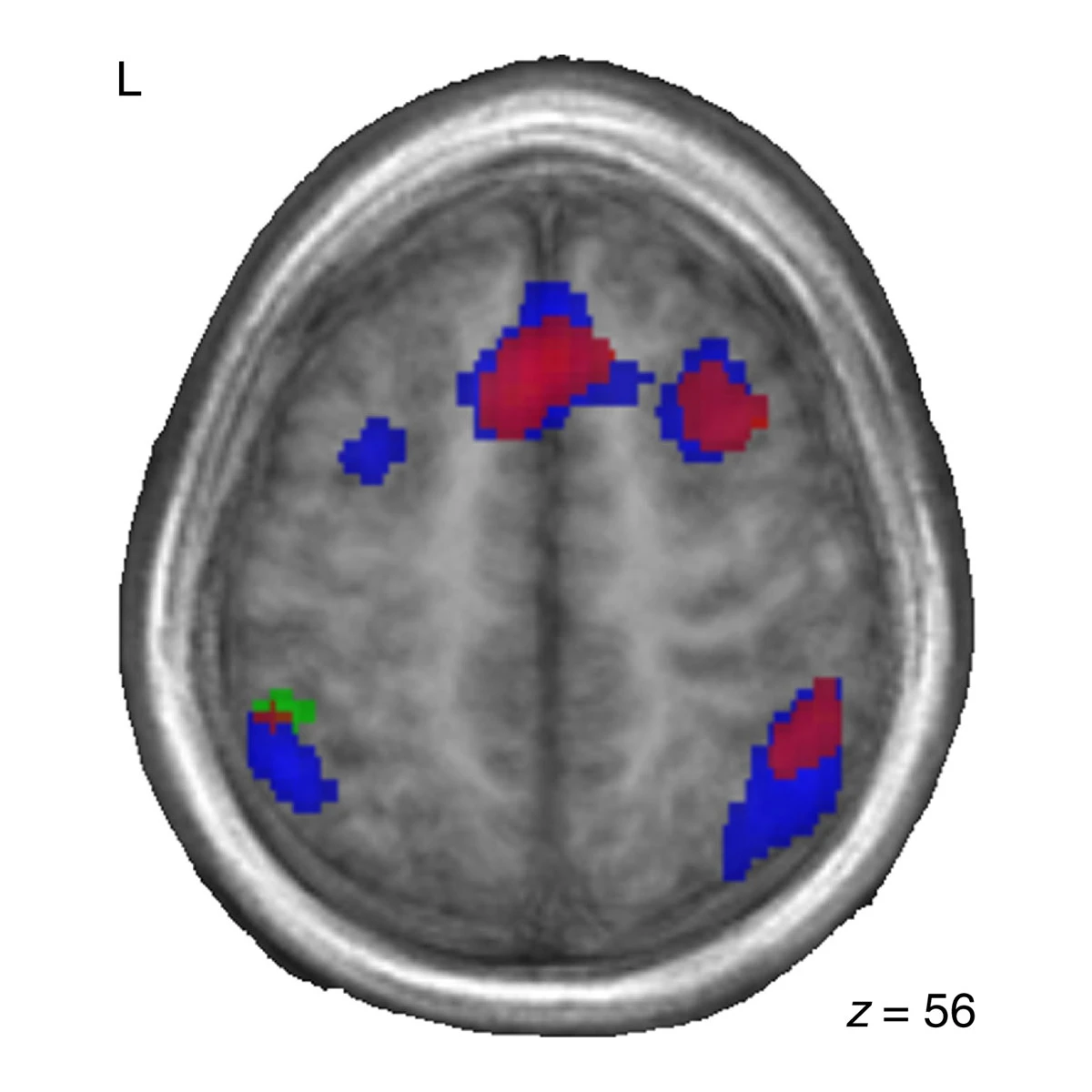

All the kids’ brains lit up in the same expected spot when they listened to the words–the left inferior frontal gyrus and anterior insula. These areas are known to process language sounds.

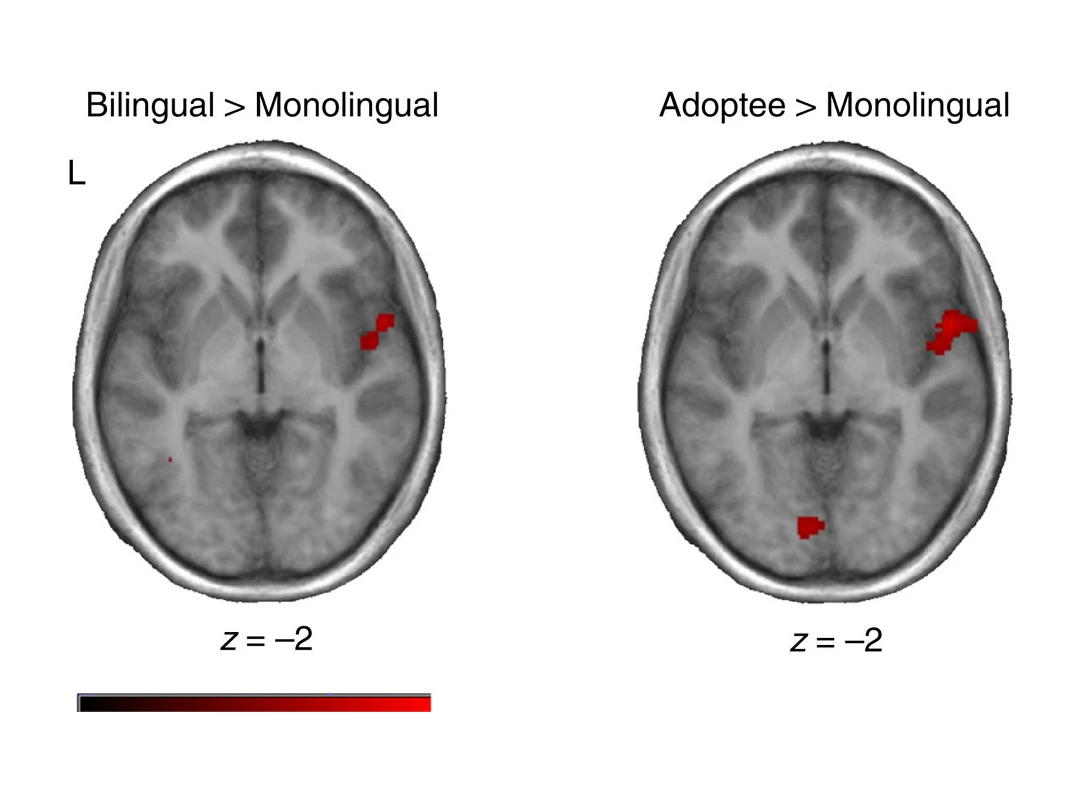

The bilingual adolescents had an additional area of activity that lit up–the right middle frontal gyrus, left medial frontal cortex, and bilateral superior temporal gyrus. The surprise result was that those adopted into monolingual French families–the Chinese kids that no longer spoke Chinese–had these same extra areas light up. They were processing French the same way a bilingual child processes French, even though they were now themselves monolingual.

What causes this difference? When we’re young, our brains are searching out any and all information. We’re also good at filtering out sounds that aren’t useful to language learning. That is, we quickly learn to know what is a word, and what isn’t. This process seems to hardwire our brains to the sounds of our first language, so that we hear all other languages through that filter, even when we no longer speak or even remember the language itself.

“During the first year of life, as a first step in language development, infants’ brains are highly tuned to collect and store information about the sounds that are relevant and important to the language they hear around them,” says the study’s lead author Lara Pierce. ”These results suggest that children exposed to Chinese as infants process French in a different manner to monolingual French children.”

This, says another study, explains why speakers of one language always make the same mistakes when pronouncing foreign languages:

“When we hear a word that does not sound reasonable, we often mishear or repeat it in a way that makes it sound more acceptable,” says David Gow, of the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Neurology. “For example, the English language does not permit words that begin with the sounds ‘sr-,’ but that combination is allowed in several languages including Russian. As a result, most English speakers pronounce the Sanskrit word ‘sri’–as in the name of the island nation Sri Lanka–as ‘shri,’ a combination of sounds found in English words like shriek and shred.”

The new McGill University study suggests that the way we learn a language when we’re young is different to how we learn when we’re older. Our innate ear for words may be what makes language learning seem so effortless as babies.

The study also raises some questions. For instance, when children are brought up in bilingual or even trilingual families (that is, both parents speak a different mother tongue to a child, while all of them live in a country with another language), are they hard-wired with the sounds of all these languages?

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.