The iPad’s lack of an apparent file system might be training the next generation of computer users to think differently about their content and the way it’s stored. And by extension, it might raise their expectations for software to unrealistic heights. From a post by Jan Senderek, the founder of Loom, a photo management startup:

Kids today who start out with iPads and iPhones will never or rarely be in touch with a file or a folder. They won’t care about the type of data created or consumed on their devices. Apps are used to generate and consume content such as photos, emails, and news. They are the new ‘folders’. To try to find a file extension on an app or mobile device is hard. The interface and experience deliberately takes away the need to know whether an image is a .webp or .webp because you don’t need to know. Even if the next generation still uses a desktop at home or at school, the iPad will shape their behavior. The next wave of consumers are using cloud-based services to consume content that isn’t file-based like Facebook, Spotify or Netflix. Content provided by these services no longer sits on a computer taking up valuable hard drive space or requires conscious awareness of the makeup of the file.

Well, except that any content which a person wishes to access offline still does sit on the computer taking up valuable hard drive space. Even kids reared on iPads will eventually figure out that these devices suffer from a scarcity of resources which requires planning. You can’t have your whole Spotify library saved offline if you also want to download several iTunes-rented movies for a long flight.

But will actually see things this way? Brent Simmons said recently on his blog that perhaps content-accessibility issues would begin to be perceived as “bugs” in the software, not natural limitations of computing constraints. (He’s talking specifically here about whether or not an app has clients for other OSes or devices, but the idea can be abstracted to mean all access issues.) With the advent of the App Store and app reviews, consumers have come to see software products as end-to-end systems; The ones which break down (whether for lack of resources or anything else) simply “aren’t syncing” correctly.

But it also illustrates an interesting change in what we mean when we talk about syncing. Note that the tweet doesn’t really talk about syncing. It talks about multiple versions of an app, which is not the same thing. Consider Glassboard. My then-co-workers at Sepia Labs did an excellent job with the backend, and syncing works wonderfully. But the non-existence of a Mac app is considered a sync bug, rather than a feature request for a Mac app. Or consider MarsEdit, which downloads posts from your blog. That’s by far the most important part of sync for a blog editor (though I could understand wanting to sync your drafts). But the lack of an iOS version of MarsEdit is considered a sync bug. I’m fine with this. “Syncing” now means not just syncing itself but the creation of multiple versions of an app that sync.

When the file system isn’t apparent, and isn’t manually managed or organized by the user, it ceases to be the concern of the user–much the way power management and software updates are now the province of the machine itself, internal issues to be dealt with internally. It’s now up to mobile developers to smartly store offline content and find ways of preventing foreseeable roadblocks to access, lest the user blame the app itself.

This an ongoing story: The Death Of The File System: What You Need To Know

We’re adding updates as news rolls in. Read on to find out what we’re tracking. Skip down the page to read previous updates.

Your computer’s hard drive is no longer the catch-all bucket it once was. Now it shares duty with software services that store data remotely, using local storage only sporadically. But those cloud services–Rdio, Dropbox, Pandora, iCloud, and Google Apps are just a few I pay for–add up to hundreds of dollars a year, presumably until you die or just stop caring. And this is your most prized content we’re talking about! Irreplaceable stuff like home videos, ripped albums, vacation photos, work documents–so what becomes of this stuff ain’t trivial.

The incumbents, Apple, Google, and Microsoft, seem to know that their lock on your files is fading–and with it, your lock-in to their OS. New “social” services like Apple’s iMessage, for example, isolate themselves from third-party networks, where legacy desktop apps like Apple’s iChat app for Mac OS X once accommodated services like AIM, Gtalk, and Jabber. What gives?

The grab for lock-in matters poignantly now as cloud services begin to tip mainstream. Today’s shortsighted storage choice can be tomorrow’s major pain in the ass, and tectonic changes in the market are ensuring that this is a problem that even the most technophobic users will begin to take notice of. Developers need foresight to ensure their users don’t get disenfranchised because of storage issues that are outside their control.

What This Story Is Tracking

There are two big trends here that seem to be coalescing. The first: segmentation of file storage across different apps and services. In a more abstract way, this reflects the larger movement of data into the cloud, but we’ll focus on the way this affects individual users, not entire systems.

The second trend: the appearance of new, viable mobile operating systems that never could have survived in the Apple-Microsoft desktop duoculture. As the big OS makers lose their stranglehold on the market for operating systems, other cloud companies will try to muscle in and create their own form of lock-in by mimicking certain features that used to be found only in native system software.

Previous Updates

Google vs. Apple: Two Theories About App Cloud Storage

Earlier this month Google announced the Google Drive SDK for developers, with an interesting : Drive is a special place where application data can be stored securely. The new properties let developers add searchable fields to data created in Drive. As Shane Shick :

The key word here is ‘searchable.’ While Google has often been criticized for spreading itself too thin by launching products that are only tangentially related to its original core competency, App Data Folders shows the company staying true to its mission of trying to organize the world’s information.

This is Google’s way of making sense of the segmentation that cloud storage has inflicted upon early adopters: Instead of trying to solve the problem from a storage perspective–e.g., allow Drive to hold all sorts of file types–the company has chosen to attach segmentation from the app side, making it easier for various third-party clients to find information that’s stored in Drive.

As Shick notes, this is in contrast to the way Apple’s iCloud works; in the latter, neither developers nor their apps have programmatic access to the contents of a user’s iCloud account, at least beyond files created by that app itself. In Apple’s model, the goal (for Apple) is to incentivize developers to rewrite their apps with a document-based data model, so their third-party apps store everything in iCloud. (In practice, iCloud has known sync issues with relational DBs created in CoreData.)

Whether Google’s or Apple’s model is more advantageous remains to be seen, but one clear lesson here has to do with ambition. In the real world, infrastructure is brittle and frameworks have legacy problems. Trying to create a perfect, elegant solution a la iCloud has resulted in disaster for the iOS developer community. Merely making cloud files easy to index, as Google is trying to do with the Drive SDK, seems like a more manageable (if less inspiring) approach.

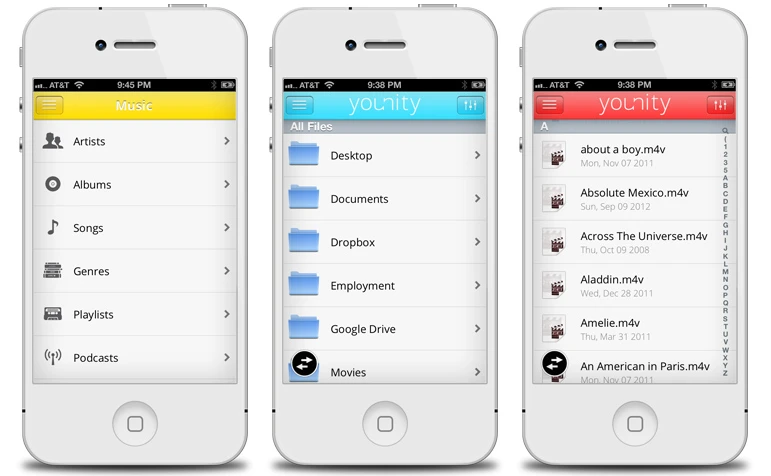

The point of Younity, the personal cloud that launched a major release today, is to make all of your data available across all of your devices cheaply and seamlessly.

We asked Younity founder Erik Caso about how developers can help eliminate the distinction between online and offline files so that users don’t have to think about where a file lives. Their solution: a patented “ubiquitous data protocol,” which is specifically designed to change the address of a file from a hard drive to an identity.

How should developers think about the concept of the file system going forward?

I would suggest to developers that they stop thinking about either/or, when it comes to cloud vs. local data. The problem with data is managed in isolation and treated as unique. So a photo on one device has no relationship to its copy elsewhere. Certainly, there are occasions when duplicates are not meant to be the same. But in many cases we are simply moving files around for use and access on different devices. This is a big problem. It is forecast that the typical American will have 5.8 devices by 2015 and that there is over 2 terabytes of files per household now. Most devices won’t accommodate all our files. If files are stuck on one device, they are isolated, so we look to the cloud to establish a single place to keep things. However, if we put all our files into the cloud, it will cost thousands of dollars a year. The economics of the “consumer cloud” is a massively limiting factor. We know enterprises will pay for high-value services, but it is no secret that consumers like cheap or free. This brings us to where we are today: We use a litany of online services that only include small subsets of our data and files and thus become a burden because we are actually managing more.

Why is that not optimal?

In reality, none of us (as individual users) care where files are as long as we can access them at any time we wish. We don’t care if they are online or offline; we only care if they are available. I’ll put them all online if that makes them available all the time, but the truth is that it is unlikely that things will never be on local storage. More to the point, there is no reason for that at all. That means there is a likely (I’d say inevitable) trend that data will be stored locally and online. Even now, huge volumes of files and media are being spread across all our devices. So if you’re a developer and building out some application, you need to embrace this reality. You need to accept that it can’t be either/or; it must be both.

How does Younity identify files as being the same, across different drives and OSes?

We fingerprint files based upon their contents to determine if they are the same across different devices. We also map the various “canonical root” directories across the various operating systems to determine if files reside in the same place, from the perspective of the user. Meaning that Younity will correctly identify the same photo stored on Windows XP as C:\Documents and Settings\Mike\My Pictures\Birthday.webp and in Mac OS X as /Users/mike/Pictures/Birthday.webp. So it will appear just once in, say, Younity for iOS, because it is the same file. This, of course, assumes that the two Birthday.webp files have exactly the same contents. If they do not, we will treat them as different files. Also, any changes to a file on one device will update the corresponding file on all your other devices. In other words, Younity knows that this is the same file and treats it as the same file in every way across those devices.

The cloud creates a false sense of security. Federico Viticci at MacStories writes:

… I’m not as anxious about backups as I used to be. With the move from local storage to cloud services, I feel comfortable knowing that my documents always exist somewhere. I see this every time I set up a fresh install of OS X: my documents, passwords, and photos are in Dropbox and Evernote, my music is on Rdio, my purchased apps are on the Mac App Store, and if they’re not, I have a license saved in my Gmail account. My movies and TV shows are on Plex and iTunes in the Cloud.

But what about media? Having tens of gigabytes of music, images, or videos makes it likely that backups are interrupted before completion or that there are sync errors because of the size of the files involved. This snafu can be attributed to everything from crappy backup software to your daily schedule–turning off your machine before it has a chance to sync those last 100 photos can create risks you’re not even aware of. We like iOS designer Craig Grannell’s reply post entitled Don’t Stop Backing Up Unless You’re A Crazy Person for alluding to these problems in context. After outlining his backup setup (Dropbox, SuperDuper, and CrashPlan) he says:

I wanted to add Time Machine to this mix (for ongoing versioned backup), but Time Machine just didn’t work with any of the hard drives I had at hand. (Subsequent Twitter-based discussions also suggested Time Machine currently has some pretty major bugs that can lock up OS X Mountain Lion in some circumstances, which happened to me a few times before I ditched the app.) I’d also be happier if everything was in CrashPlan, but until British broadband gets out of the stone age and offers decent upload speeds, I have to be a little more selective.

The file system may be dying, but it won’t be totally cold until these segmented cloud solutions begin to interact with each other (and system software) to ensure that everything really is saved where it purports to be.

Very few companies are attempting to reconcile the fragmented ecosystem of local and cloud storage. Why? We asked one such company–Bitcasa, which offers infinite (that’s on beyond a Googleplex) cloud storage for $99 a year. Bitcasa claims that the efficiency gains from their patented deduplication algorithm is the key to their profitability at this price and performance point. Data deduplication is a relatively recent technique developed to prevent duplicate file storage and transmission. The hard part, says Bitcasa founder and CEO Tony Gauda, is all the cross-platform testing, which makes solving this problem a real bear. (And you thought cross-browser testing was a pain.)

If you’re doing Web development, you know that certain Web browsers maintain consistently, for example, IE this way, Chrome this way, etc. But it’s not the same when talking about operating systems on OS itself. It is an environment that has multiple variables–for example, someone can be using a Mac OS in Chinese with Google local installed. There are also many different hardware [specifications] that need to be adapted to, and some have faster processes than others–it [depends on] the complexity of the environment. Making it work is all about testing, testing testing. We test on seven platforms and let [tests] run for days with multiple configurations. Changes can’t go instantly. Also, a lot of people don’t upgrade! So as the user base increases, there are more variables. But we are getting much better at understanding what these variables are to ensure everything works consistently on every platform.

Tony Gauda, who spoke with FastCo.Labs reporter Akshay Arabolu, is Bitcasa’s CEO and founder, and the product’s patent holder.

Don’t like the UI on your HTC Android device? Rebuild it. HTC has open-sourced the code to its front-end experience, HTC Sense, for dozens of devices and geographies. As discussed earlier in this story, preference for UI becomes one major source of user lock-in when all your files and apps are in the cloud. Whether or not this decision could massively backfire is a question open to debate. Will technical users customize their HTC devices, turning themselves into more dedicated HTC users? Or will the company simply water down its design choices with the assumption that people will “fix it if they want it fixed”?

Allowing people to restructure your UI is a tacit admission that you haven’t solved (or hell, even considered) many of the use cases your users will run into. Is that HTC being refreshingly honest, or abysmally lazy? From 9to5Google.

The advantages for Facebook are obvious, assuming the company is beginning a track to build their own phone and OS. It’s not clear what HTC gets in return. Via AppleOutsider:

Time. Home significantly increases Facebook’s mobile presence without being everything. A lot of time and care seems to have gone into it, but it’s surely far less than a full-blown operating system would require. Installed base. Built in. The sales pitch is very simple: If you have a device that Home supports, download it. No money, no switcher headaches. Blackberry and Windows Phone sales prove that people aren’t looking for new platforms right now. Software Experience. Facebook’s engineers have surely learned a lot from this project. That experience will be reapplied not only to expanding Home itself, but to building a full-blown OS if they want. Hardware Experience. While the software is the real news here, Facebook took the initiative to also start working with a handset maker. The HTC First is hardly a “Facebook phone”, but it’s a chance for Facebook to experience the complexity of coordinating hardware, software, and carrier partnerships from a distance. Remember the Motorola ROKR? Remember what happened fifteen months later? HTC was the obvious choice. Samsung and Android have ruined [HTC] and they’re desperate to stay relevant. Facebook likely got everything they asked for.

This is the crux of the argument, which also highlights how unbalanced the Facebook/HTC deal appears to be:

Facebook has loudly and confidently entered an arena it has no prior experience in, and has set a clear path to expand its influence at its own pace. Facebook Home will provide a halo effect to current Android users that warms them up to a full-blown “Facebook phone” in the years to come. It gives Facebook the experience, confidence, credibility, momentum, and time to build a better and broader mobile experience than they would have been able to build otherwise. It’s as prudent as it is ambitious.

One assumption that might not be valid for long: that we create more data every year. Or rather, that the new data necessarily needs to take up more space, and cost more money. Some companies have foreseen the hockey-stick growth of human data creation and are working on more efficient ways of storing things to control costs. Dell is one. Via a Dell white paper I just discovered, released last fall:

[Dell’s Fluid File System] addresses challenges that organizations face by allowing them to gain control of their data, reduce complexity, and meet growing data demands over time… [A]rchitecture is open-standards based, supports industry standard protocols, and provides innovative features relating to high availability, performance, efficient data management, data integrity, and data protection. As a core component of the Dell Fluid Data architecture, Fluid File System brings differentiated value to the various Dell storage offerings. It is a network attached storage (NAS) file system accessed using CIFS and NFS protocols, but it has features and enhancements that make it unique, as discussed in the remaining sections of this document.

Here are some of the problems Dell wants this system to address:

- Data silos prevent easy access to vital business information.

- Data migration, backup, and disaster recovery are complex, consuming administrative time and resources.

- Meeting data growth by deploying more and more storage systems increases both the administrative burden and capital expenditure at a time when businesses need to run lean.

- Traditional file systems have scalability limitations that make them unwieldy for organizations with rapidly expanding file data.

If anyone has any insight into how these distributed file systems might work for individual users–in other words, in a consumer use-case–please let us know via Twitter. The main use-case is unified protection and replication across data sources[/url], which presumably become a valuable consumer service if “consumer clouds” remain as segmented as they currently are, but grow in scale. Via Infostor:

The move provides a unified foundation to deliver data protection and replication across storage systems that handle both block and file data. Getting Fluid File up and running on the Compellent architecture was the last hurdle to offering file protection and management across each of the company’s primary storage platforms, according to Dell.

As OS lock-in dissolves, Dropbox is looking for ways to introduce its own lock-in. As we saw with Facebook Home, each contender in the new “OS wars” is staking out territory, picking the content they think users need most and trying to own that content in an attempt to lock in the user, either by necessity or by taste.

Because the files in Dropbox aren’t silo’d–these are documents, movies, and music files which can be read by most any machine–the company needs another way to tie you to Dropbox as your cloud of choice. They’ve wisely picked to link up with email, a tool which for most people has high lock-in potential, since it’s a pain to change email addresses. They’ve accomplished this through a partnership with Yahoo in which mail attachments get saved directly into Dropbox. Via the Dropbox blog:

Since this integration is Dropbox-powered, you can even send that big album of vacation pics without worrying about the 25 MB file limit. Plus, it’s easy to save any photo, video, or doc in your Yahoo! Mail straight to your Dropbox, where you can get to it from anywhere.

When the file system becomes abstracted, UI is what matters most. And because mobile devices are limited to one screen at a time, it’s crucial that a mobile OS have a great interface for executing workflows between apps in a way that makes sense.

One reason the Windows Phone has struggled is the limited number of actions available on content; the platform lacks the hooks (in iOS) or intents (in Android) that make it easy to integrate a third-party actions into some of the most commonly used stock views, the way ActionSheets in iOS do, for example. So despite what this guest author from Microsoft says on Wired, it actually doesn’t much matter whether all of your data is cached locally, sync’d to the cloud or whatever. The cloud is at its best when you’re risking data loss, or on the road without access to local storage. But most of the time users are merely trying to get things done–and that’s why Windows Phone has stumbled even as more users move to smartphones and cloud services. It doesn’t allow app developers to position their programs as links in a longer chain of actions.

I’m a Microsoft employee so you should apply the necessary filters to what I’m about to say, but here goes. With Windows 8 on multiple tablets and laptops, and a Windows phone, and Office apps that run full-strength when they can and in the browser when they can’t, and SkyDrive syncing everywhere, and a People hub that unites all my email and Facebook and Twitter and Skype contacts across my cloud of devices and services, I’m a happy camper. If all you’ve heard about Windows 8 is complaints about the start screen then you’re missing the real story. It’s an operating system that thinks rather deeply about the personal cloud and works hard to make it real.

That this is Windows’ limiting factor is evident enough from the comments you’ll find on stories like this Gizmodo post: The people who are most supportive of Windows Phone are often users with basic computing needs and no motivation to string apps together into workflows.

I’m not a very heavy App [sic] user (I stick mostly to texting, surfing the web, and web apps if necessary) so I’m more focused on the hardware. My Lumia 920 is amazing for me. It’s really durable, I love the bright red color, and the screen is beautiful. The camera is nice too, but it’s only useful when I have to take a picture of text since I don’t take many pictures otherwise. I’ve had no issues since I switched, personally. That said, it makes me sad how little support WP8 gets.

Another misconception is that normal users are confused or preoccupied by the fact that files in the cloud end up stored redundantly. Indeed, many documents I save in Dropbox also get saved to iCloud when I edit them there–things didn’t use to work that way. But actually, this redundancy is more like a fringe benefit–more copies mean it’s easier to find things and harder to lose them–and the idea that something is stored remotely isn’t a hard concept. Plus, simply not losing things is a step up from the local storage paradigm. So why are users not more clearly enthusiastic about migrating all their stuff into the cloud?

The Web teaches us this way of thinking. But we don’t easily learn it. I think a lot about reasons why not. A major one, I’ve concluded, is that we bring millions of years of primate evolution to our experience of the Web. In the physical world that was our only home until a few decades ago, objects were singular and lived in only one place. They weren’t easy to replicate, and they couldn’t form clouds of linked replicas. In the virtual world this magic seems to happen naturally, the effects are surprising, and it’s going to take us a while to get used to them.

It’s intuitive that an app should retain content it edits, rather than storing it in some hierarchy. What’s confusing for users is that a single file today, when accessed on mobile and desktop devices, often needs to be modified by several different apps in the course of a workflow. This is a far cry from the desktop software paradigm, where file formats were more proprietary, and all the actions available on that file were right there in the program that created it. To be useful and user-friendly, an app really needs to focus as much on features as the way it interacts with other apps.

Facebook sees the incumbent OS makers losing their grip. Today the company is staking out what it believes to be the three must-have services in one centralized Facebook hub. If they can own these three buckets of your data, then it’s much easier to dragoon you into using other Facebook apps and services that rely on them. Via 9to5Google:

The tweaked version of Google’s Android operating system will put a Facebook user’s content right at the forefront of the operating system, integrating Facebook apps like Messenger, photos, and contacts into an easily accessible form.

Big OS makers are going to spend as much money as it takes to stem the change. Nothing threatens device makers like the proliferation of operating systems and app-centric cloud storage, because it turns their hardware into a mere carrier. Ham-handed corporate habits make them too stubborn to be interoperable–iCloud doesn’t connect to SkyDrive, for example–which means that while they’re stalling change, they’re not doing much to solve the problem for users, as iCloud, SkyDrive, and Google Apps augment the complexity by creating more segmentation. Via Tom Tunguz:

Because end user applications and experiences differentiate these filesystems, I expect to see a flurry of acquisitions of next generation content creation tools that users love by these companies all in effort to create loyalty and build lock-in to a particular file system.

Apple, Microsoft, and Google have a hard time even accepting each others’ apps should exist on their respective mobile platforms. Considering that no such restrictions are enforced on their desktop OSes (and considering that desktop OSes like Mac OS and iOS seem to be converging) it will be interesting to see if intra-platform hostilities increase or decrease from here. The grand prize goes to anyone who can explain why OS makers defend the brand purity of their mobile UX so much more than their desktop platforms. Via MacRumors:

Back in December, it was reported that Apple and Microsoft were at odds over SkyDrive, with Apple refusing to allow any updates to the app after Microsoft launched paid storage tiers for the service. Apple’s rules require that developers offering any sort of paid content or service through their apps use the company’s In App Subscription mechanism, which nets Apple 30% of revenues. Developers are also prohibited from including external sign-up links in apps to direct users to external addresses where they can purchase such plans without going through Apple.

Who needs loyalty anymore? When all you need is a bunch of cloud-enabled apps to access your stuff, it becomes frictionless to move from one device or OS to another. That may mean more OSes are on the horizon–let’s hope increasingly specialized ones? Via BBC:

The [Firefox OS] platform is based on the HTML5 web programming language and is being marketed as offering software writers more “freedom” than alternatives. However, it faces competition from other soon-to-be-released systems. Blackberry 10, Ubuntu, Tizen and Sailfish are all due for release for smartphones before the end of 2013, joining a market already occupied by Android, iOS, Windows Phone, Blackberry 7 and Symbian among others.

That’s a lot of OSes. But Timothy Lee highlights an excellent point: Because of the disruption befalling OS makers, Firefox OS doesn’t actually need to win marketshare, because it can still accomplish its goals without a majority of users on Firefox devices. Via Arstechnica:

Firefox OS could have a big impact on the Web even if it never gains significant market share. By pushing the Web forward, Mozilla is helping to ensure that mobile websites will continue to be relevant even as developers create hundreds of thousands of proprietary apps. Firefox could lose the battle for the smartphone OS market but still win the war for open standards.

As Mozilla CEO Gary Kovacs said at Mobile World Congress in February, the growing number of smartphone users actually necessitates that the market for OSes grow in complexity. Quoted in ReadWrite, he says:

I find it impossible to understand how 3, 4, 5, or 6 billion people are going to get their diverse needs satisfied by one or two or five companies, no matter how delicious those companies are. Is the farmer in the Indian countryside going to have the same needs and requirements as a lawyer sitting in New York?”

Virtualization might (finally) be a reality in the workplace. Sure, this ReadWrite piece is guest authored by a guy whose company sells virtual infrastructure–but just because he’s shilling doesn’t mean he’s wrong. If virtualization is finally here for real in the enterprise, it will create tectonic changes for everyone; trends in enterprise and consumer software are often interrelated, so the notion of desktop as a service may become an expectation of some enterprise workers when they use their home computer. Via ReadWrite:

Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) was supposed to address many of these challenges, but it came with its own set of issues. While it has been promoted as a technology that can save businesses money, large upfront capital expenses and complexity have created barriers to virtual desktop adoption. With DaaS, savings come from operational expense reductions from centralizing and reducing administration and hardware savings over time. DaaS delivers faster desktop deployment, enhanced security, less downtime and lower support costs – and can enable a truly mobile workforce.

No file system is a no-go. This is the deepest analysis I’ve found of a vision of a future in which “users simply have apps” and are not conscious of storage repositories. And it doesn’t bode well for workplace users. We may need new UX paradigms. Via JohnnyHolland:

“Documents associated with them appear magically. Presto.” While this might sound like some kind of user experience utopia, I have a grave concern that eliminating a file system in this manner misses a huge audience. Us. While opening Pages to work on the family newsletter might make sense for casual home users of a computer system, it does not make sense in a professional context. In the professional world, we work on projects. Projects are composed of many different types of files. And yes, we might have the same apps open all day, but do we want to be forced to duplicate a hierarchy of information in every single application? No. Besides, “projects” are just one type of organizational scheme. As a user experience designer, I’ve seen a lot of professionals in other fields organizing a lot of stuff in a lot of different ways. So even attempts at inter-app organization around the concept of a project, such as Microsoft’s Project Center, are not effective replacements for an infinitely flexible organization scheme like simple folders.

Author Fred Beecher goes on:

We still need a high-level organization system of some kind. And that is the challenge. It’s a challenge because that problem has already been solved by the file system. The challenge is to solve it better. At Interaction11, Tim Wood called for designers to reject the “complacency artifacts” of the past, design patterns that have lost relevance in the modern world but continue to be used simply because that’s how things are done. He encouraged us to be bold enough to reinvent wheels that need reinventing, and that’s exactly where we’re at with file systems. Gestural user interfaces, effortless portability, and ubiquitous network access… All these things and more are redefining how people interact with technology. UX designers need to recognize this and push themselves beyond the limits of our vision.

Here are five high-profile Mac developers bitching about iCloud. If these guys can’t make it work, it’s officially broken. That leaves Apple vulnerable to abandonment on behalf of their historically loyal and talented developer base. Via Rich Siegel:

“Just works” might be the customer experience; but developers must do more to support iCloud (or any new OS technology) than simply flipping a switch. Things can go wrong, and they often do… In general, when iCloud data doesn’t synchronize correctly (and this happens, in practice, often), neither the developer nor the user has any idea why.

Efficient data storage methods might render the whole problem moot. The idea that the “file system” is headed for tectonic changes is predicated on the continued growth of our data. More efficient storage methods could allow us to keep creating new information while allowing our storage media size to plateau. (If you’re working on Erasure Coding or anything comparable, drop me a line on Twitter and explain whether this supposition could come to pass.) Via DataCenterKnowledge:

Indeed, applications are gradually taking over the role of the file systems, making the latter obsolete. Those applications often run far more efficiently when they talk to the storage directly, without a file system in between – by using REST, a standard interface that comes with Object Storage platforms. A much more efficient approach is to build storage pools based on an Erasure Coding approach. This technology was first used for communication with deep space, when messages had to be understandable even if parts were lost in the transfer. EC works like a Sudoku puzzle: blanks can be calculated based on the remaining information. Data Objects are split up in many small chunks, from which calculations are generated (with some small overhead). Those calculations are stored on the system, as widely spread as possible. When a disk (or a larger unit) fails, the data can still be read since they are calculations. Missing data can be re-generated.

Stay Tuned As Coverage Continues!

[Image: Flickr user Alexander Rey]

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.