In the movie Maestro, American conductor Leonard Bernstein’s wife, actress Felicia, says to him: “If summer doesn’t sing in you, then nothing sings in you. And, if nothing sings in you, then you can’t make music.”

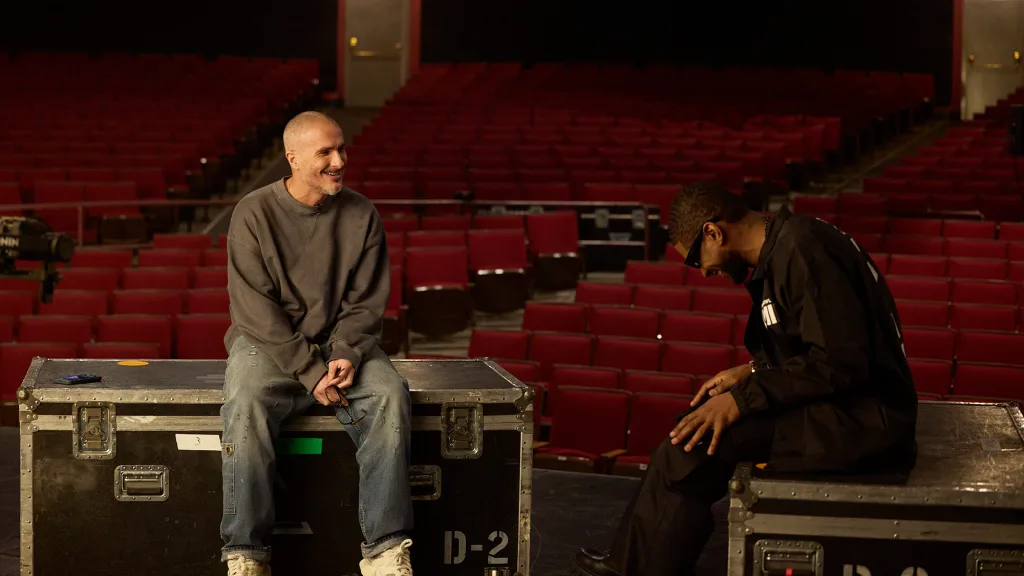

If there’s one person I knew the quote would resonate with, it’s Zane Lowe, Apple Music’s global creative director, head of Artist Relations, and host of his eponymous interview series and radio show. Celebrated for his contagious passion, I was curious about what sings in Lowe. What music does he intend to create and share?

“I am drawn to the full spectrum of the human experience,” he says, lit up by the quote. “I can flip very quickly from something that speaks to me with a dynamic energy, something that inspires me, right down to something that makes me feel incredibly sad . . . The most common criticism I’ve gotten is: You like everything. My answer is: I know, it’s how I’m built. What I’ve learned is that I’m searching for the most authentic version of whatever it is, and it’s got to have some teeth. It has to have flaws because I find feeling in flaws . . . I want to see and feel it all.”

This devotion illuminates Lowe’s conversations across generations and genres, with artists ranging from Shakira to Yo Yo Ma, Billie Eilish to Mick Jagger. More importantly, it’s made him their confidant; Whereas musicians rarely enjoy doing interviews, they seek Lowe out. As a DJ, host, and musician himself, he’s cultivated this connection over the past three decades. Still, at its heart, it’s much simpler than that: Lowe is a fan. “I’m just trying to stay a fan in a big room,” he adds. “I’ve got to be that fan.”

In our conversation, the music industry veteran opens up about discovering his deeper purpose with musicians, the art of balancing music and business, and overcoming fear in the creative process.

Fast Company: In your conversation with Yo Yo Ma, he shared that when you interview people you get them into their subconscious. How do you get artists into that state? What have you learned is most essential to building trust?

Zane Lowe: There are layers to trust. From a conversational point of view, I want them to know that I listen to the music. I feel the music and, in doing so, am able to hopefully talk about the music. I want them to know [that] I get the art and I appreciate the effort that they put into the art. That, to me, is page one of the artist’s language handbook—empathy and understanding of what’s required to make it.

Then, I want them to know that I’m listening to them in the moment, which I was not very good at. I liked the job more than I understood my role or value in the job for a long time. I like the art. I like the people who make it. And, I like my role in it. I like, like, like. I didn’t really understand what my actual purpose was in it and how I could be of service to it. I thought I was doing enough, but I wasn’t actually making the most of it. What I had to learn was that I had to disregard the job, look at the experience I was having with people, and figure out what is most important.

What was most important was that I really listen to someone, what they’re saying, how they’re saying it, why they’re saying it, and what it takes to say it. Silence used to terrify me in this scenario. Now, I love the silence because I know someone’s really contemplating their thought. I used to fill that gap. Now, I let it sit.

In The New York Times, you shared that you shifted from focusing on the work to illuminating the spirit of it. How do you understand, and then create space, for a person’s spirit—and the spirit of their work—to flourish?

I cared about my work, but I didn’t realize how far we—as in me and whoever I was talking with, and the audience—could go together. So, I was in this loop of: This is the trade. You come in. I ask you about the producers and the music; the fans like it, the music comes out, and we do it again. I was uninspiring myself.

I did some self-work. I started going to therapy again. I started to better understand what I was searching for in terms of just being self-motivated. Discovering new parts of myself, so that I could have more to offer. I started listening to myself more and ignoring the things that felt like I was in a loop. I’d be talking to someone, I’d go to interrupt them, and I wouldn’t act. I’d be, like Stop. That’s what you would do normally. Do the opposite.

Then, I would wait and I would get a different result. I got really into different results. I started searching for parts of what I was doing that could have benefited from a different result. It led me into these conversations without even really meaning to go there. I just was open.

So, when I’m having conversations with an artist and it’s getting deep, it wasn’t like I was going there trying to emotionally mug somebody. I was going there because I was willing to let them go there and not stay in that subterranean loop. I was like: If they’re willing to dive deeper, have the courage to go there with them, and don’t be afraid to let them. Trust that you have the tools to support the conversation. It’s a human experience. Let it be human.

Also in The NYT, you reflected on Mike Skinner saying that “you have this unresolved artistic ambition” and shared that: “I really want to continue to learn the language of the artist, and how they think and how they speak, because it’s in me. I just haven’t been able to speak it as fluently.” In the four years since that piece was published, how are you speaking it more fluently and how has it influenced you as a creative?

That has been a huge thing for me. I’m trying to better understand what’s motivating the process and the need and desire to create. I’m getting better at it and it helps me in my other job. As someone who runs an artist relations department, a fundamental job is to translate and communicate what our business feels is important [to be a good collaborator on this project], and also translate and explain what’s important to the artist and what principles drive this project for them. And, make sure that there’s a mutual understanding, so we can do great work together.

So, there are times I have to say to people in that job: We have to try again. And, they’re like: Why? You haven’t even asked. And, I’m like: I don’t want to, because you don’t want them to say “No.” I talk to managers all the time [who say]: He’s just not ready to talk. I’m like: They shouldn’t. “No” is a powerful word and it makes the “Yes” more meaningful when they’re ready. I don’t want to ask someone to do something when I know in my heart—because I’m getting better at speaking the language— that they’re going to say “No,” because what it says is: You don’t understand me or what’s driving this or you wouldn’t even ask.

You get much more meaningful experiences and collaborations when you’re mixing the art and the business. I do it on the other side, too. The artist [says] We’d like to do that. And, I [say]: We’ve got to try again because that’s not going to work for us, but there’s a solution here. It’s balance, right? Finding a way to create opportunities through meaningful dialogue. To me is the most important thing. We don’t [communicate] enough and, as a species, we don’t do it well enough. When the opportunity presents itself, I love the idea of trying to do it well.

You’ve been open about the role that fear plays in your creative process and shared that: “There’s always gonna be a little part of me that wishes I’d been a bit more committed to the creative process rather than perfecting it.” How have you learned to manage your relationship to fear and how has that elevated your creativity?

I’ll be really honest with you. I’m still afraid. I don’t think enough emphasis gets put on the courage it takes to execute on the arts. We all get obsessed with the process, as we should because it’s magic…But, a lot of the artists I know, I get a sense that letting go can be really tough. I think it’s where a lot of fear creeps in—How will this be perceived? Will I be understood? I still haven’t figured that out.

I’m making a lot of music in my own time. I’ve got my kids saying to me: Working on that project for a while now, pops! I’m like—Yeah, I’m struggling to execute—because I want them to know that it’s okay to feel that way. Managers will say to me: So, when is this [episode] going out? I always say the same thing: I don’t do “when,” because you don’t want me in the edit [figuring out what it is]. I give notes and make sure it comes out in my voice, but I don’t helicopter edit. I’ve done that and made bad decisions for the end result. I’ve gotten in my own way.

There’s an interview I did with Kanye West back when I was at Radio One [in 2015]. It was a pretty seismic event in my life. It was when he really opened up to the fashion industry and went head-on in the camera about what he wanted to achieve. It was a big deal at the time and trended worldwide number one. It was the first taste I had of Oh wow, a conversation can be a hit. But, in the moment, after about eight minutes of talking about music, he pivoted and it became a very different conversation for 90 minutes.

I came in the next day and my producer said: What’d you think of last night’s interview? I said: I don’t think it was an interview. I feel like I asked four questions. I wasn’t evolved in terms of how I relate to my own ego and role in this stuff. I said: I’m not even sure it’s usable. I was in a tailspin on it . . . He said: I’ll tell you what. Put the headphones on [because he’d been listening]. I’m going to press play, and when you get to a point where you want something cut out, come find me.

I put the headphones on. He came back 20 minutes later and said: What do you think? I was like: Put it all out. I nearly didn’t execute on something that changed my life. From there, it was Jay Z, Eminem, Rick Rubin—all within six months. That really set me on this pathway to everything that’s happening now. But, if you left it up to me, I might’ve pulled it.

In your interview with Cate Blanchett, you shared that “Every great artist will get to a point where they’re willing to let go of any expectations or anything they’ve achieved before; where they’re willing to absolutely ignore the ambition that drove them as a young person and almost start all over again. I think that is when you start doing your best work.” It seems like you’ve arrived at that point. How has it changed the way you work and define success?

I stopped looking left, right, and trying to veer into lanes thinking that I could change the flow of traffic and be of use there. I stuck to what I know I love to do, focused on doing my best work, let go, and waited for things to start coming to me through the filter of what I do, not trying to do what others may do. It was a powerful thing to let go of.

That was a big part of my younger life: I can do it all. But, should you? So, what happens when we break through the clouds and don’t see what’s going on on the ground anymore? So, we’re not chasing those goals and in that traffic and thrash. We’re in clean air. It’s got to feel like one of the most hard-earned results of your life to say: I did all of that on the ground so that I could get here. I know that I can always come up here and go back down there. But, I’m going to make up here because making down there is distracting and hard. So, can you get above the clouds?

I think that’s when you grow up and you’re like: I’m not motivated by those things anymore. It’s great fuel, but I don’t think it’s where you should end up. I think you should be striving to go up to 30,000 feet where you’re only seeing the sky. That’s the goal.

You harness music as a tool to cultivate a greater sense of empathy for ourselves and each other. If you had to choose one song to leave us with, what would it be?

My mom has dementia. Anyone who has a friend or relative with dementia will tell you that the conversations are so scattered that you end up in a strange way feeling like a fraud because they’ll say something and you go, Oh, yeah—but you don’t know what they’re saying. You’re just trying to provide company. So I thought, I’m going to play some music. I played “Piano Man”—she loved Billy Joel—and she changed. All of a sudden she started actually looking at me. She started squeezing my hand. And then, everything fell into focus enough for her to comment on the music. Then, it was Joni Mitchell. Then, it was Neil Young—all the classics. She started inherently remembering the melodies. Then, even the odd word came out. This happened over the course of an hour.

The second day I came in, I didn’t even say hello. I just played a song. She woke up and started moving. It was the closest thing in a long time I’ve had to having a really meaningful experience with my mom where I felt like we saw each other. That is what music does. It is inherently connected to the emotions and feelings that are in us that then trigger our memories and remind us of how we felt in that moment. Music is magic.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.