What was the world like before Netflix? Increasingly, we don’t really remember. Now with 260 million subscribers around the world, the original streaming entertainment service established an entire industry—one that feels more crowded by the day.

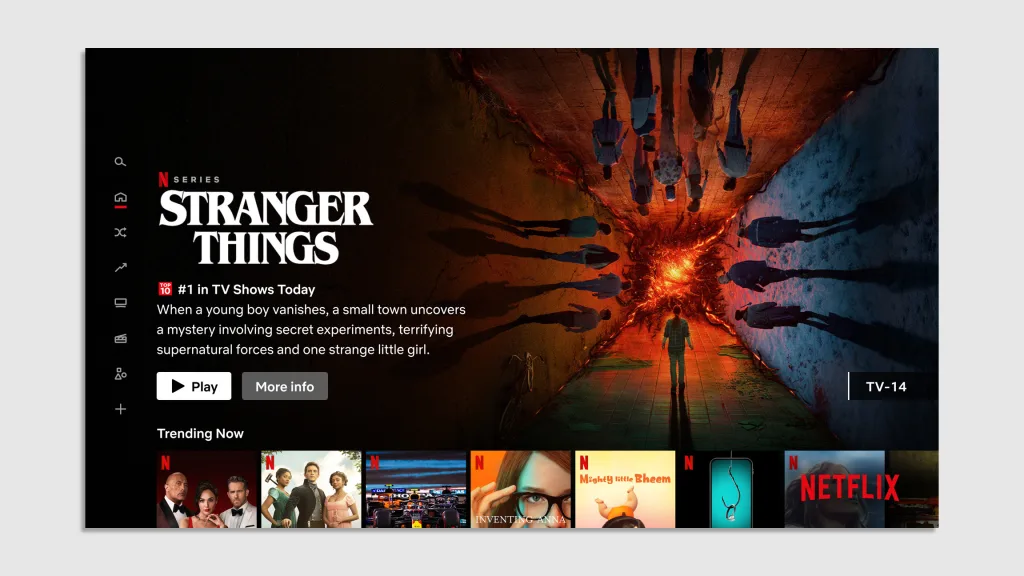

Netflix currently has half a dozen serious competitors ranging from Disney+ to Amazon Prime—but it’s still the leader, if by a slight margin. Especially in terms of its design, the interface established by Netflix still proves to be the norm. All other streaming services are mere variations on the theme.

And yet, on a random Wednesday night, you or I can still turn on Netflix and have absolutely no idea what we want to watch.

It’s a challenge that still keeps Steve Johnson, Netflix’s VP of design, up at night. How does a company that serves 100 billion hours of media a year make sure people “discover” what they actually want to watch?

Johnson joins me from his apartment in Los Angeles, with a surprising backdrop of several pinball machines. For a designer defined by his digital work—before landing at Netflix in 2016, he led design and user research at both LinkedIn and Adobe—these “analog bits” from his childhood still define his aesthetic and ground his perspective. “I have an 8-bit Ms. Pac-Man machine back here,” he says with a laugh. “It just kind of reminds me, we have all this crazy Apple Vision Pro stuff now—when I was playing that thing!”

Over our hour-long discussion, Johnson answers every curiosity I’ve ever had about Netflix’s interface, business priorities, and future-thinking head-on. And he makes a very clarifying case as to why, even though Netflix is a $240 billion streaming company, it’s still so dang hard for it to know what you want to watch next.

This Q&A has been lightly edited for clarity.

The challenge of Discovery

We’re in an era when the standards of streaming UX have been established. I think everybody came around and pretty much copied a lot of Netflix’s good work in this space. But now that work is done. So what’s the focus of your work at Netflix today?

I can’t use the word copied [laughs]. All of our competitors have flattered us with their rendition. But I mean, look, here’s what I think we’re all chewing on. Discovery is huge. And it really is because we have so many great competitors out there. And at the end of the day, our UIs and their UIs, it doesn’t really matter. It’s about the shows and stuff that people want. People just want great stories, especially coming out of COVID.

I think I’ve always believed that life imitates art, which is why I’m surrounded by all the things that inspired me as a kid. And I think right now, people want a level of escapism. So when I’m looking for something to watch, how do I discover it quickly? How do I find it quickly? And how do I help make sure that it’s also worth my time?

How is that problem unique to Netflix?

We all market these things differently. Disney shows were marketed before you even saw them. I could say, tomorrow, that there’s a new Disney show about an ink pen that’s finding his way through the world, and he perseveres! [Since] we understand the Disney storyline, we are already ready to agree with that. So even if we’ve never heard of this show, we’ve already heard the story, and we’re already welcoming it.

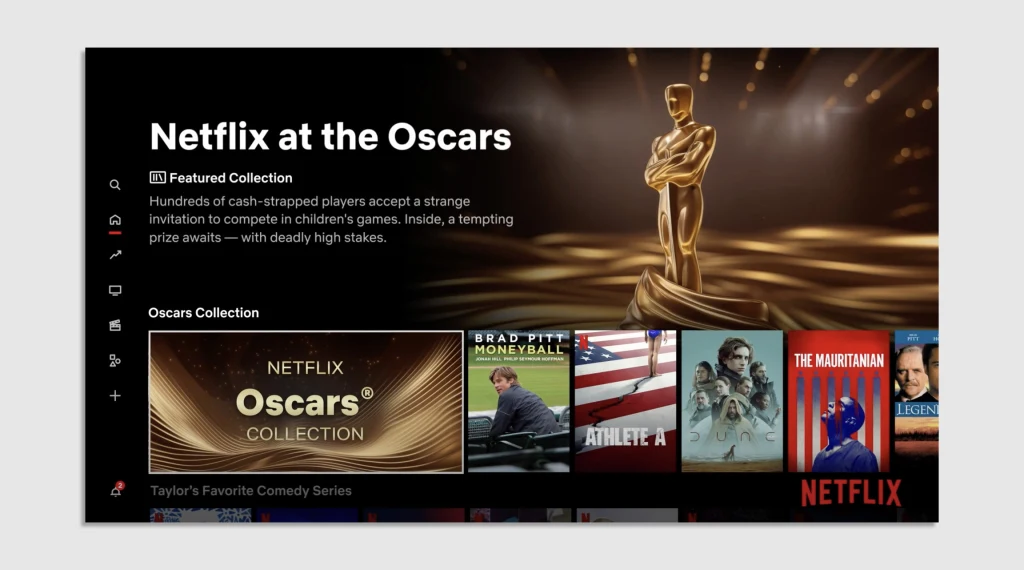

At Netflix, we have such a diverse population of shows in 183 countries around the world. We’re really trying to serve up lots of stories people haven’t heard before. When you go into our environment, you’re like, “Ooh, what is that?” You’re almost kind of afraid to touch it, because you’re like, “Well, I don’t want to waste my time.”

That level of discovery is literally, I’m not bullshitting you, man, that’s the thing that keeps me up at night. How do I help figure out how to help people discover things, with enough evidence that they trust it? And when they click on it, they love it, and then they immediately ping their best friend, “Have you seen this documentary? It’s amazing.” And she tells her friends, and then that entire viral loop starts.

Discovery is an interesting problem, because if I went to Netflix and asked this same question a decade ago, the answer would have largely been “discovery.” I remember when you had the million-dollar bounty on this topic!

Around discovery, the biggest revolution from my own viewing habits has been seeing your Top 10 chart, which is about two years old at this point. It instilled a sort of immediacy, and a comfort in answering, “What is everybody watching?” All of a sudden, I’d find it very grounding when I entered Netflix, rather than just having endless libraries of things I could potentially like.

Let me ask you something really fast, before you ask me the next question. I don’t disagree with you. [Since] we designed it and we put it up, it’s been very successful. So I’m not putting it down. But I just always like to ask, why do you care about what other people you don’t know are watching?

There’s a level to which everybody wants to be able to follow the conversation of what’s happening. I also suspect that it passively connects me to other people who are also using Netflix in a silo. We don’t see each other, obviously, and I don’t want to social network on Netflix. But knowing other humans exist there is part of it.

You answered the question absolutely perfectly. Not only because it’s your truth, but that’s what everyone says! That connection part. So another thing that goes back to your previous question, when you’re asking me what’s on my mind? It’s that. How do I help make sure that when you’re in that discovery loop, you still feel that you’re connected to others.

I’m not trying to be the Goth kids on campus who are like, “I don’t care about what’s popular.” But I’m also not trying to be the super poppy kids who are always chasing trends. There’s something in between which is, “Oh, hey, I haven’t heard about that, and I kind of want to be up on it.” I know lots of people who aren’t sports fans who still check the scores before they go into the office, just so they understand what people are talking about.

So how do we help make sure we have a great discovery engine, but then also make people feel that they’re kind of a part of something? Because that’s the one thing that I think we’ve lost from linear television. At least you knew that everybody was probably tuning in Tuesday night at 8 to watch XYZ.

Do you feel like Netflix actually understands what I really like? I mean, we talk about discovery as the problem of how you serve up Netflix shows to a person. But I do wonder about that source data.

I believe our system has a better-than-average understanding—60% or better—of what member number 75227342 possibly likes. We have no idea if it’s you or anyone else.

Right, it’s anonymized.

The discovery engine is very temporal. Member number 237308 could have been into [reality TV] because she or he just had a breakup. Now they just met somebody, so all of a sudden it shifts to rom-coms.

Now that person that they met loves to travel. So [they might get into] travel documentaries. And now that person that they’re with, they may have a kid, so they might want more kids’ shows. So, it’s very dangerous for us to ever kind of say, “This is what you like. You have a cat. You must like cat documentaries.”

We’re also incredibly multifaceted, depending on where we are with our own lives, where we are geographically, what’s going on in the world. The system is never designed for just one thing. It’s always designed for, “This is what they like for now.” Maybe like a week.

Can Netflix change my viewing habits?

I consider my own consumption habits a lot. I used to see one to two movies in a theater a week. I am definitely down to one or two a year at this juncture. But I have found my tastes change. I have a tough time watching dramatic things at home. I will watch people do terrible, sad things in a movie theater. That’s great! But at home I can’t overcome that inertia.

I’m curious how you think about things like that. Does that ship sail for someone like me? Do you want to intervene?

Tell me if this answers your question. This is going to be a little bit of a tie-in to what you brought up with Top 10. There is what the system perceives you have enjoyed, and then we want to give you more of that. There’s what the system perceives you may enjoy, based on what you have enjoyed, but then also things like Top 10 and regionally what we think that other people like.

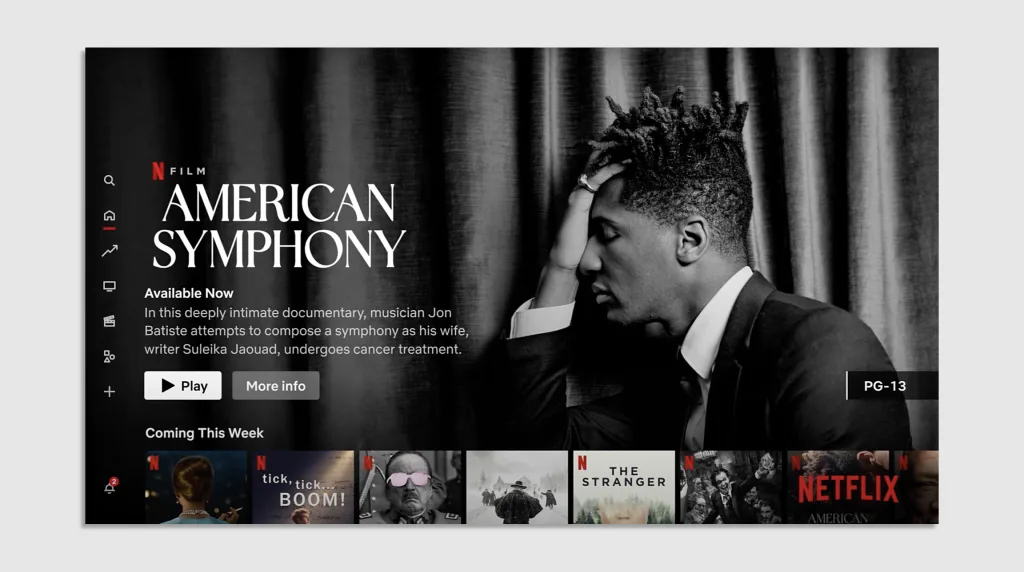

And then there’s just, “Oh, hey, by the way, have you heard about this?” Right? That’s just good old-fashioned marketing and promotion, which we definitely want to do.

At Netflix, we don’t put our thumb on our scale for our content. We just want you to enjoy Netflix. So if you take a look at this Top 10 right now [in February 2024], you’re going to see all kinds of movies. You’re going to see Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. You’re going to see Top Gun Maverick. Those aren’t “ours,” but they are things we think that you might enjoy. We’re always trying to put that up.

Now, your point about watching dramatic things at home, let’s go one step further. Imagine if you live in a multigenerational household in a country like India.

Uh oh, I can sense a very Men In Black-style zoom-out coming.

In a household environment in a country like India, it’s normal to have your parents live with you, and particularly your grandparents. Now, on that huge 55-inch flat-screen TV that’s in the living room, you definitely don’t want things that come up and offend your parents! So that’s another place where we have to be really careful in never making an assumption that we know exactly who you are and what you’re watching. We want you to have your own profile so we can tailor those things in, but we also know that people have different viewing behaviors and they have different households.

The discovery system you’re describing as you’ve built it sounds like how Microsoft talked about inclusive design years ago—the idea that inclusive design is really, in part, about adaptability, that people feel differently on different days. And even one individual is not the same over the course of a week. It sounds like when you’re approaching discoverability, you’re building a system that you at least aspire to be as malleable as a person. It might operate differently on different days, serve things up differently on different days based upon a best guess or tracking what I’m interested in.

Yeah, that’s the holy grail. I think that we’re all chasing it. Every single one of us. And I won’t mention any of the competitors by name, but you can probably figure this out: Some of our competitors whose catalog is really one type of content have a much easier time with that because they kind of take the Apple approach of, “Not our customer.” So they don’t have to watch, right? If you’re not watching sports or if you’re not watching family or if you’re not watching home and garden, if that’s not your jam, we don’t care. With ours, we really want to bring you stories from everywhere.

Look, if someone had said to me five years ago that I would be bingeing K-drama constantly, I’d be like no way! It’s because I was exposed to those stories. I never thought that I would like them, and I found myself one Friday night being like, “Oh, next episode, next episode.” It’s when we get that wrong that people say, “Why are you showing me this? I don’t want to watch this crap!” And you have this allergic reaction, almost like I invaded your home, went into your refrigerator, and put the food that you’re allergic to front and center.

Exactly. Sometimes I look at Netflix and I’m like, “You’ve got to know I’m never watching that.”

We have to find really easy escape hatches for people to say, “Not mine,” and then also explain to them why.

Something else: I get this question all the time, too. “Why did you show me that?” And then I very snarkily say, “Why are you sharing your account?” And their face is like, “Well, oh.” That’s another reason, when we started cracking down on account sharing, it wasn’t necessarily just for the purposes of revenue. It was really so we could start to streamline, making sure that the stuff that you see is the stuff that you want to see, because when your mother and your uncle and your best friend from college and your ex-housekeeper all have your username and password, all of their viewing data is coming into our pipeline of who we think you are, and then you start seeing things that you would never watch.

I’ve (stupidly?) paid for my own Netflix for years, but I get your point. It’d be like being a vegan, always going to the same restaurant. They know your order. And then your steak-eating dad comes in disguised as you, and yeah, he’s going to get the chickpeas.

Dude, I’m going to use that. I’m not going to attribute you at all.

No, that’s fine. That’s why I’m here.

Put my hands together on stage and I’m going to say that but yet you’re not getting any residuals for that. That was a fantastic analogy. You’re totally right.

Perfection. This is a really basic question, but I do want to make sure that I understand it: Why does it matter to the business of Netflix that I get that I am presented with things that I want to see? I feel like the assumption is that if I see it and I find value, I’ll continue subscribing to Netflix.

Two reasons. From a design perspective, the reason is because we want you to feel that you’re in the best environment for you to be entertained. And [we’re not retaining you through] stickiness from the perspective of [deploying] UI dark patterns and that kind of thing. That’s one of the reasons we make it really easy for you to cancel. I truly believe that we probably have something that you would enjoy. If you hop out of Netflix, I haven’t done my job to help people find it.

On the flip side, it’s because we’re a publicly traded company and it’s our job to help make sure that you don’t unsubscribe. If you don’t find value with our product, then you go to one of the pluses [e.g., Paramount+, et al.]. Looking at your credit card bill, you might say, “Well, we don’t use this one. Why don’t we just cancel it?”

Yeah, that happened with my Paramount+ this month. Literally had to go through my credit card yesterday. And it was like, “$6 a month? What am I spending on this?”

The part that’s always been really interesting to me is that we never reviewed that bill with the cable companies, even though we had 500 channels at $250 and we still had commercials. Think about that.

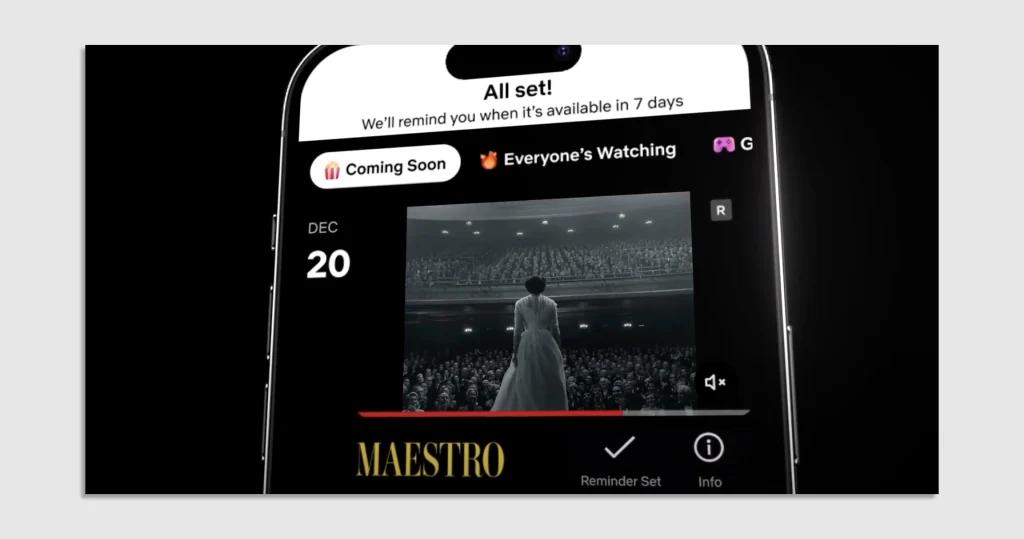

If you were to ask, “What’s the second thing that keeps you up at night?“ It’s related to that. How do I make sure that we are creating value for a generation that spends a majority of their viewing hours here [gesturing to his phone].

What’s Netflix planning for the future?

I’ve written about how wonderful channel surfing was as a low-cognitive-load task. It was, in many ways, terrible because all we had was sitcoms, but I think that very quick UX of being able to cycle through different content was really sticky.

For a long time, I wondered where we were going to see it digitally. Snapchat kind of did it with its little Stories circles, and then I think TikTok came around and just like, boom, that was it. They figured out it wasn’t a click, it was a flick. But I haven’t seen that feed-surfing experience from Netflix. I’m sure it’s been considered. I’m sure it’s been prototyped. I’m sure it’s in a lab somewhere. And why not?

Let me try to give you the best answer that I can. I used to love channel surfing too as a kid, but I only had 13 channels, and I had the little dial. Maybe if I dipped into UHF I’d finally come across some kind of 1950s sci-fi, but for the most part I didn’t have a choice. But here’s the other thing: Those shows were all 28 minutes long. There wasn’t a huge commitment, and nothing else was competing for my time. I think that what happens now is, in this world of maximum choice, most importantly that little black device that’s sitting in my pocket that for some reason I always find in my hand, I can just go do something else really fast.

And I think that the lack of having a captive audience has made it [such] that if I don’t give you the lasting impression of something that you really wanted to watch quickly, you’re not going to come back to me.

I used to love Saturday night when I was a teenager. My friends and I would walk down to Tower and we would go through records and stuff and hang out all night, grab some burritos, and just really have fun. That idea of being able to live through all these different kinds of media was really cool. But my kid does that right now with his thumb on YouTube.

Exactly.

But if he finds something to watch, I think it’s two and a half minutes long. It’s not a commitment to where he has to now say, “Okay, let me let the story arc build up to where I can figure out what the strife is of which our primary person is going through, and how hopefully they prevail at the end so I can have a sequel.” That kind of thing. When you and I used to channel surf as kids, it was never on the hour when shows started cleanly. It was never 8:30. It was around 8:42.

Definitely, you caught things in the middle constantly.

And I broke in the middle of the story [and it was fine]. And that’s something else that we have talked about and definitely tried, and it doesn’t work. I said, “What if?” about four and a half years ago with one of our failures, which was called Instant Joy, where something was just playing.

I said, “Hey, instead of that thing starting from the beginning, what if it starts in the middle?” Everybody looked at me like I was an alien. Like, “No, wait a minute. How many times have you guys watched Back to the Future since it came out?” Hands slowly rose. I’m like, “Why?” Sunday afternoon, sitting at home, nothing to do, channel surfing and all of a sudden, “Oh, I came across Back to the Future.” Did it start from the beginning? No, it was like that DeLorean was going through the thing. But the thing that I did not realize was it was breaking into the middle of that story that you already knew. Almost like—

There was already an anchor. It wasn’t a discovery, it was a rediscovery.

Exactly. That’s why things like Instant Joy didn’t work. Things starting from scratch made you go, “Oh, what is this? I didn’t ask you for this.” And if you put it in the middle, you’re like, “What is this? I don’t know what’s going on.”

But even without starting in the middle, it sounds like you’re saying the other problem is that flick modality doesn’t scale to most modern Netflix content like it does TikTok. Could you make content that would fit that modality? But I guess that’s no longer Netflix, if you’re suddenly changing a whole lot of things to match the modality.

It goes back to the thing I said at the top of the conversation, which is discovery. We could, in fact, do that, if you break into the middle of the Seinfeld episode that you’ve seen 61 times. But I don’t think that is discovering new content that you love. It’s not the system that we want to create.

Apple released the Vision Pro. [Ed note: It’s since flopped.] Netflix didn’t create an app for it. Why not?

Because when the Vision Pro came out, I knew that there was a Disney+ app. When I was asked [by others at Netflix], what do you guys think? I said, let me see what the device is first, what the adoption rate is for a $3,800 mechanism that I’m not quite sure if it’s for entertainment or utility.

We are an or company, not an and company. So do I want to apply design resources to that, or do I want to find a way that I can increase discovery for all of the devices that we’re currently on?

I get that argument. I was still surprised you didn’t put two people into porting a Netflix app quickly.

It’s got to be epic. But it’s also this, though: Now that I’ve played with it, I’m like, wow, this is the Iron Man HUD, this thing is the future of a future that I didn’t know was going to be a future. Then I go—and I’m so glad that work bought this for me because this thing was $3,800—the battery dies in about an hour and 15 minutes, and I really don’t like any of the apps in it. I am looking forward to seeing what Apple does with this and then figuring out more, how are people going to use it? Then I think that we should have a real discussion about how Netflix does it.

But to just port Netflix over? No. It’s got to make sure that it’s using the power of the system as much as humanly possible so that it’s really making that an immersive experience. I don’t want to put resources toward that right now.

I have to say the public response narrative has been very predictable. People got their hands on it and were boasting, “I can put a thousand screens up in my house! This is wild! This is the future.” Then a week later it’s like people are returning them.

I think if you’re fully immersed in the Apple ecosystem, it’s perfect by design. But I have a Nest thermostat here. I’ve got my iPhone here, but I also have my Android phone right here. I’m currently on Google Meet with you guys, but I have my Zoom window open for my next meeting. Think for a second right now that I can’t even send a photo to my friend on my iPhone who’s on an Android phone! Those kinds of barriers make it something that’s not that immersive if I don’t live in your galaxy.

What are you thinking about that’s not discovery?

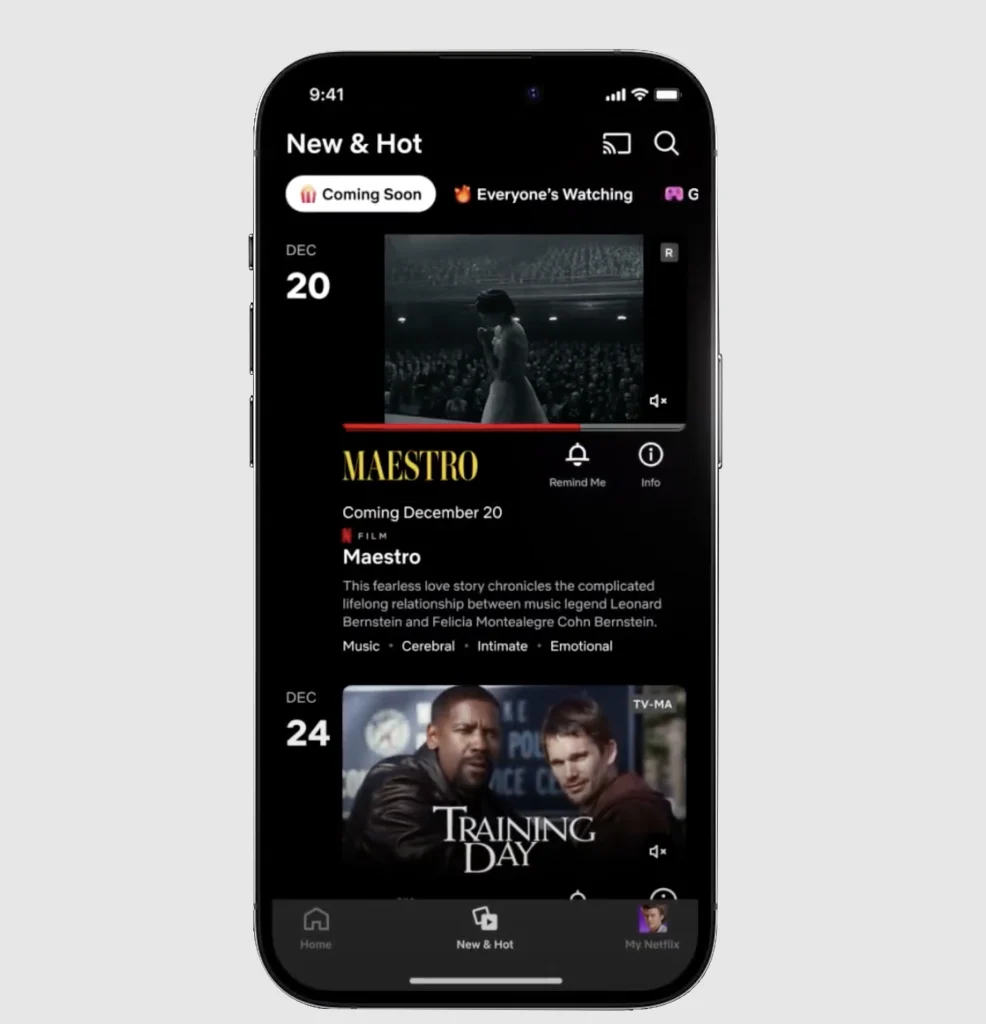

Design-wise, I think there’s always going to be the presentation layer: We’re always working on new ways of [presenting media], and we always want to try to push the envelope on that. How light and airy is the app relative to the phone? A lot of people say to me, “I don’t watch on the phone, but I want to use the phone to actually sort and to set up.” But then there are people who are like, “I pretty much watch on my phone.” How do I understand the differences between those use cases is something that we’re always playing with. In a lot of cases it’s depending on age or country. It’s who and where.

It is fascinating. The whole idea of a typical user I know is somewhat of a myth, but it feels especially so in your case.

My wife’s best friend will say to you that she has heard all of our documentaries, but she’s never seen any of them. I sit back and say, “What are you talking about?” She turns on her phone, she puts on her AirPods, and she goes for a run, and she’s listening to our docs.

She’s podcasting your docs, basically.

She may be the only human being who does that! (But I’ll almost guarantee you that she’s not the only human being who does that!) That’s something we’ve never designed for. Are we going to design for that? Probably not. But it is great to know that that’s another really interesting way that people consume our content.

I think that we’re always looking at, since we do have data, what do we believe the predominant use case is, and how do we help make sure that we could simplify that?

Back to what I was saying earlier about us being an or company—since we’re an or company, we’re not going to chase every edge case because if we do that, then we can’t do something else. But if I begin to find that people under 21 are listening more than watching, oh, that’s interesting. Now consider if there’s something there so that I can be their destination maybe instead of YouTube.

What about interactive, branching narratives? It was a great experiment in 2018 with Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.

Branching narrative was one of my favorites. The design team here at Netflix, we played a really big hand in how that worked because we had to design the back-end tool. What people don’t know about our team is 30% of our organization is actually designing and developing the software tools that we use to make the movies.

We had to design a tool that allowed the teams to understand both what extra footage to shoot and how that might branch. When the Black Mirror team was trying to figure out how to make this narrative work, the software we provided really made that easier.

Now, your top level question of what do I think of branching? I loved it. I thought it was great, and people didn’t use it as much. The reason, I believe, is because there was something about coming home from work, wanting to be entertained, and actually not wanting to make a decision.

I hear that. I feel like the FOMO of the branch is always hard too. It’s like, you just want the best ending, right?

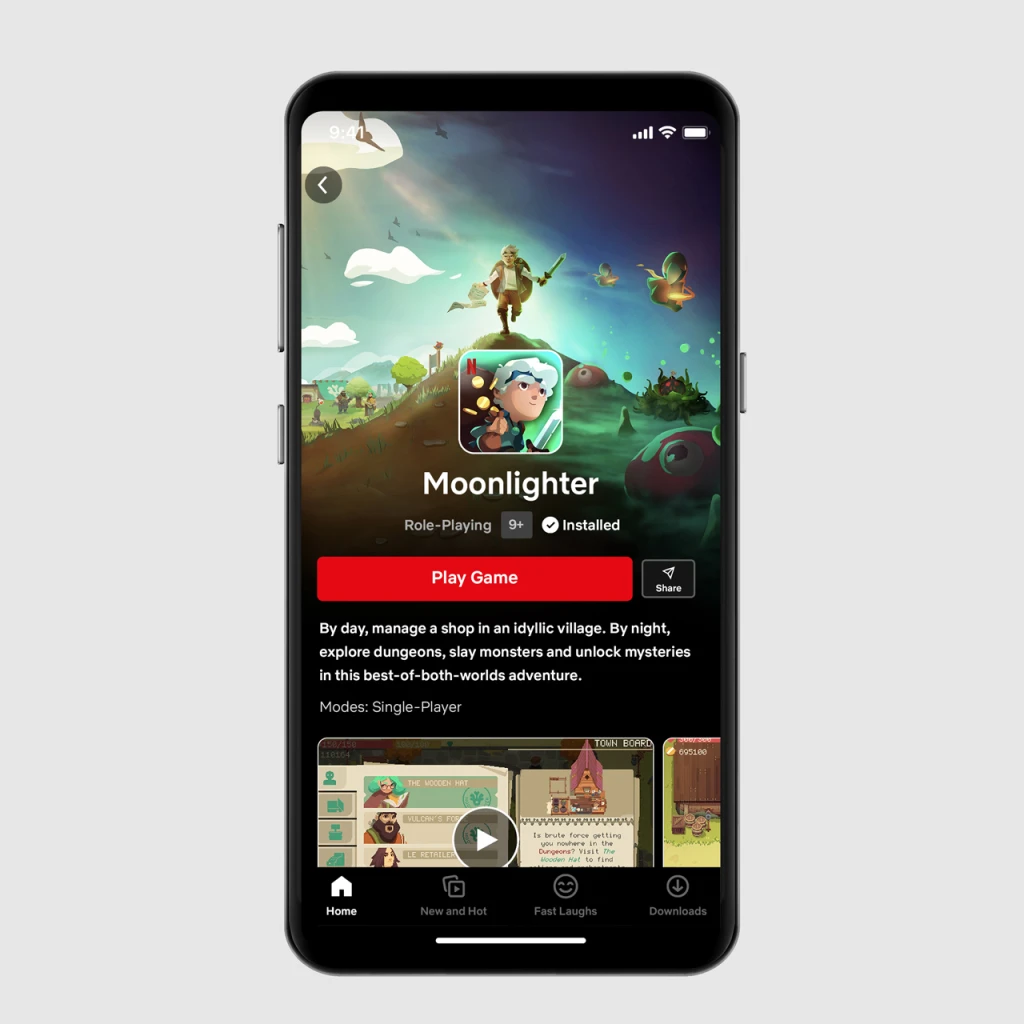

Yeah. So I don’t know if Bela [Bajaria, chief content officer] is considering any future branches, but right now it’s not something that I’m putting the team’s time into. Now let’s flip forward: We do have video games. Being able to offer you a game on your couch or on your phone . . . you can click your QR code and you can go into that—that, to me, is the second-best thing. Since I started my career at Electronic Arts, I won’t lie, I am hoping that maybe within the next few years we do have some intersectionality there, but that’s not anything that’s currently on my roster.

Streaming gaming is quietly getting big and capable. After years of theory, suddenly both Microsoft Xbox and Nvidia are rendering complex games in the cloud to play locally.

A Netflix of gaming will always be the most enticing headline to me, but exactly how that lives and breathes—and especially within the competitive set—becomes difficult for me to really conceptualize, I guess.

I think that this one for me is back to what we were talking about earlier, even generationally and where you’re doing content and where you’re being entertained and what you consider a pastime. If I am standing in line in the DMV and I currently am number 432, and they announce number 5, all right, I might pull my phone out, and now what do I want to do? Do I want to resume a show that I’ve already been watching? Do I want to find something new? Or do I want to play some fun little game? Whatever that thing is, it’s all on my mobile device. So in order for us to make sure that we can continue to beat the predominant source of entertainment on your mobile phone, going into gaming makes perfect sense, right?

When you’re asking me questions about the Vision Pro and even interactivity, both of those things to me are more when you’re home—they’re about capturing the living room [versus mobile].

In all it’s just, how do you want to pass your time? What do you want to do? We want to make sure that we provide for all of the screens: be it your phone, your tablet, your web browser, or your TV. And that’s why you see us dipping into all these different types of media. It’s how you do it and what you’re doing it with and who you’re doing it with. We need to make sure that we’re there no matter which one of those answers you take.

But it sounds like you feel that with gaming, mobile is probably the sweet spot.

I believe that for now. But I let myself be open to get new information that makes me go, “Oh, I didn’t think about that.” There was no Vision Pro just a year ago.

How are you thinking about generative AI?

I’m going to caveat all of this with, whenever I talk about AIs, I’m talking about design tools. I’m not talking about replacing actors and actresses because I know that that’s an incredibly sensitive and hot-button topic.

Fairly so.

From my perspective, AI is—and please forgive the snarkiness—it is just a very well-branded set of technology that we’ve been using for quite some time, but now people gave it a name and that’s kind of made it a thing. I worked at Adobe for 11 years, and we were always kind of developing tools that if people did things repeatedly over and over and over, we said, “Why don’t we do that for you?” And that’s what I’ll call AI.

With generative, I think that the tools that we’re currently using, like Figma and other tools, they’re really kind of going deep in it for the purposes of making repetitive things a lot easier. Being able to grab things that are already out there, but faster, and being able to assemble them.

I’m not the person who thinks that it’s going to replace the ability for people to be creative because AI tools only know what people have done. [AI] doesn’t really know what people are going to do in the future.

They’re recursive by nature.

Yeah, and you’re going to start to see the scenes. Look, don’t get me wrong, when I saw the OpenAI Sora demo, I’m like, “Holy shit.” I don’t think that these AI tools are necessarily bad in any way. I think that they’re just productivity tools . . . that are going to make it easier for the three of us to create and build something a lot better.

I will say this: What I love about them is that they democratize the ability for new filmmakers to get stuff done. I don’t necessarily know if you’re going to need so much bureaucracy with other people telling you what to do with your art, versus you can just build it and put it out there. I liken it a lot to companies like Avid back in the early music days to where the three of us might be a band. We would have to go through a record company to get our stuff out. And by the time they soil it, it’s nothing that we wanted it to be.

If we were starting a band right now, we could just put out our stuff! I see that as being similar to what AI tools are going to be providing people in the future. I think it’s super exciting.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.