Many companies dream of dominating the era of artificial intelligence. But hardly any can flip a switch and instantly put their AI in front of the eyeballs of a meaningful percentage of humanity. One of the few that can is Meta, which reaches nearly 4 billion people a month via Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Messenger.

Before I delve into what it’s doing with that vast platform, some Fast Company tech stories you might not have read yet:

- Why streaming platforms are scrubbing the soundtracks from your favorite shows

- Tesla had a miserable quarter. Why is TSLA stock rising?

- What happens when we train our AI on social media?

- Apple quietly beefs up its AI division with acquisition of French startup

Last week, in its biggest gambit yet to make AI a core part of its apps, Meta deployed a new version of its Meta AI chatbot to users in 14 countries. Instagram’s search tab, for example, isn’t just for finding content tied to specific users, keywords, and locations anymore. It now invites you to “Ask Meta AI anything,” making it a doorway to open-ended chat sessions about any topic. A stand-alone edition of Meta AI is also available; like the in-app versions, it’s free.

The new Meta AI leverages Llama 3, Meta’s latest large language model—by all accounts a formidable rival for OpenAI’s GPT-4 from a technical standpoint. In my decidedly unscientific experiments, the experience felt close to ChatGPT Plus in many respects, without the latter’s $20-per-month price tag. I asked the bot to do everything from help me tweak WordPress code to make up text adventure games, and was usually pretty happy with the results.

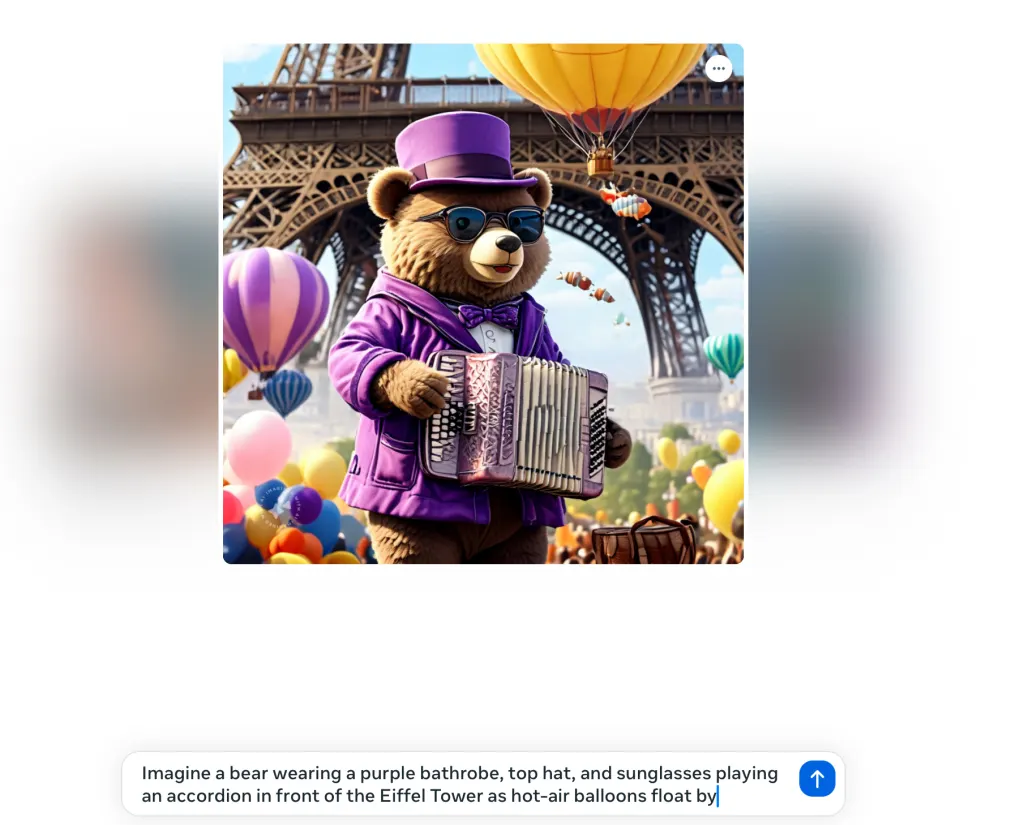

Like ChatGPT Plus, Meta AI has a built-in image generator that can churn out pictures based on text prompts. Called Imagine, it can’t match the mind-bendingly sophisticated graphics from ChatGPT’s DALL-E 3, but it does add a showstopping new twist. As you type a prompt—say, “Imagine a bear wearing a purple bathrobe, top hat, and sunglasses playing an accordion in front of the Eiffel Tower as hot-air balloons float by”—it constructs the image in real time, letting you see the elements fall into place one by one. It even figured out some of what I was entering mid-word and gave me what I wanted before I was done asking for it.

Overall, the new Meta AI certainly makes a better first impression than Google’s hapless Gemini, which continues to deflect straightforward questions such as “Where did Jill Biden go to college?” by suggesting I “try Google search.” Meta AI’s answers to my queries are clear, conversational, and to the point, in contrast to Gemini’s sometimes cloyingly garrulous responses. Still, while I haven’t found it prone to obvious hallucinations like those that bedevil some bots, it did make its share of more subtle mistakes that are, in their own way, at least as devilish. No, Meta, Snoopy was not known as “Snooky” in his earliest appearances in the comics.

Almost 17 months after ChatGPT’s debut, it’s still not a cakewalk for other AI botmakers to ship products in the same zip code, quality-wise. That Meta has done so is impressive. But in its current incarnation, Meta AI comes nowhere near answering a critical question: What can Meta do with its LLM technology that’s not merely roughly equivalent to ChatGPT but uniquely useful in ways that other companies can’t match?

After all, the fact that Meta AI now lives inside Meta’s flagship apps doesn’t mean the company has come up with any compelling reasons for it to be there. Instead, the bot feels bolted on, as if its presence is about distribution, not utility. That presumably helps explain why a fair number of users’ gut reaction is to try to turn it off. (For now, you can’t.)

Any general-purpose chatbot—capable of offering anything from cookie recipes to life-coaching advice—runs the risk of feeling superfluous inside a social or messaging app. In a worst-case scenario, it’s an impediment, as it was when I was trying to search Facebook for posts relating to a long-defunct Chinese restaurant. Instead, Meta AI provided the eatery’s supposed hours of operation and delivery fees—which, since it no longer exists, were not exactly helpful.

The thing is, Meta may have more opportunities than any other tech giant to improve its products through inventive use of AI. Mark Zuckerberg has been talking about the power of the social graph—the myriad data points reflecting how the members of a service such as Facebook are connected to each other—since late 2007. That happens to be almost exactly when I signed up for an account. Despite the 16-plus years of information about my usage the service has accumulated, I rarely get the sense that it understands me well. Properly applied, AI could change that in ways that transform the experience for the better.

For now, Meta AI makes my time spent in Meta apps less personal, not more so. In Facebook, it suggests some topics for me, such as “Online dance classes” (I don’t dance), “Make a moving checklist” (I’m staying put), and “Japandi bedroom inspo” (I have no idea what that is). One of its few suggestions that indicated some knowledge of my interests was “Sergio Mendes’ upcoming concerts,” but the ones it listed, it turned out, have all been canceled.

Shouldn’t Facebook automatically generate text descriptions of photos, which would enhance accessibility and open up the possibility of audio feeds? What if WhatsApp and Messenger could summarize a group conversation when you entered it in progress? Wouldn’t it be neat if Instagram came up with ideas for Reels based on its understanding of what we’ve posted in the past? These aren’t my concepts—actually, they’re ones Meta AI came up with in response to the prompt “Give some examples of ways generative AI could make Meta’s apps better.” I approve of them, though, and have no trouble generating lots more on my own.

I’m not arguing that more distinctive approaches to AI necessarily represent progress. Last September, Meta announced an army of chatbots “played” by celebrities, from Snoop Dogg to Naomi Osaka, that felt like the work of a company that had more money to burn than useful ideas to implement. Even in its current, disappointingly generic implementation, the new Meta AI is a step up from that. But given the potential for AI to keep users glued to their screens—and exposed to even more ads—Meta is surely working on many efforts beyond those we know about. I hope some of them reach our phones, tablets, and laptops soon.

You’ve been reading Plugged In, Fast Company’s weekly tech newsletter from me, global technology editor Harry McCracken. If a friend or colleague forwarded this edition to you—or you’re reading it on FastCompany.com—you can check out previous issues and sign up to get it yourself every Wednesday morning. I love hearing from you: Ping me at hmccracken@fastcompany.com with your feedback and ideas for future newsletters.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.