A baby born this year will turn 80 in 2104. By that point, the U.S. might have heated up by 10 degrees Fahrenheit, even more than the global average. Throughout his or her life, hurricanes and wildfires and floods will keep getting more destructive—and that will impact their bank account.

For the average American born in 2024, climate change could mean ending up nearly $500,000 poorer over their lifetime, according to a new report from Consumer Reports and the global consulting firm ICF. If the analysis included more uncertain factors, the cost could be closer to $1 million.

“A lot of discussions around climate change are frequently framed around the environment,” says Chris Harto, a senior policy analyst at Consumer Reports. “We really wanted to take a much closer look at how it would affect people.”

You’re probably already losing money because of climate change. Extreme heat is pushing up energy bills. A flood or wildfire might have damaged your house. You might be paying more for insurance (and the value of your house might drop if it becomes uninsurable). You’re paying more for foods like chocolate as crops get harder to grow. But as climate change progresses, costs will keep rising.

“The effects of climate change are already hitting consumers,” says Peter Schultz, vice president at ICF. “We expect as climate change increases in the future, those impacts [will] increase and become what we refer to as nonlinear—to increase in severity over time.”

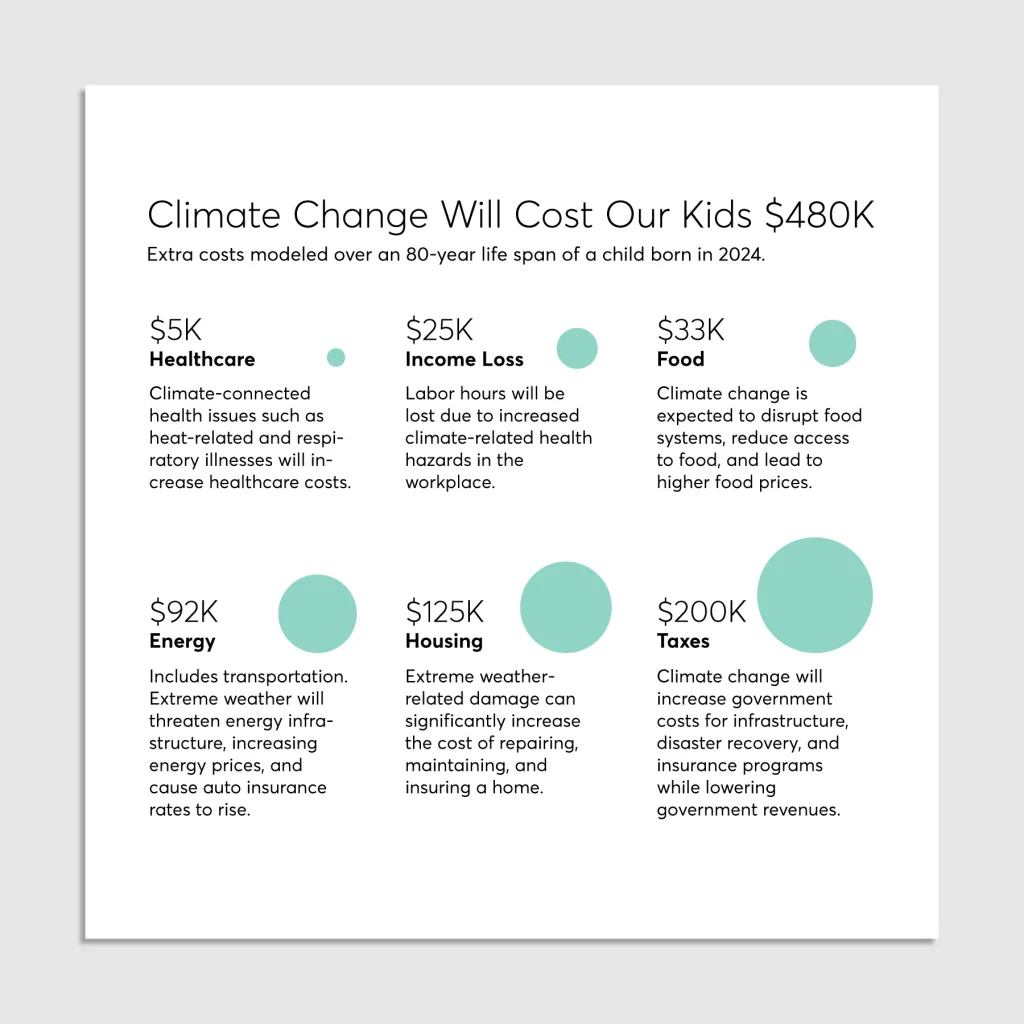

How the individual costs of climate add up

Floods, fires, and other climate-fueled extreme weather will make it more expensive to repair and insure homes. Someone born this year may pay $125,000 more for housing over their lifetime. The cost to cool homes will also rise. Electric utilities may also raise prices to cover the cost of repairing infrastructure damaged by extreme weather. (Total energy bills might rise by $88,000). As extreme weather disrupts agriculture, food could cost $33,000 more over their lifetime. Health problems triggered by extreme heat could cost $5,000. Car insurance costs are likely to rise as extreme weather makes crashes more likely.

At the same time, taxes will increase—by an average of $200,000 over a lifetime—as the government has to pay to repair roads that melt in the heat, for example, or cover rising healthcare costs as extreme heat affects heart disease and other chronic conditions. Incomes could also drop. The report looked at the most obvious job impact: People who work outside in construction or agriculture will lose hours of work because of extreme heat.

But salaries for office workers could also be lower because corporations hit by climate change will look for other ways to save costs. That’s one example of a potential impact that isn’t included in the analysis. The report also doesn’t include how climate change is impacting inflation, for example. Climate change is also likely to increase global insecurity, which could raise taxes.

One of the biggest costs is likely to be a drop in retirement earnings, but it’s also not included in the conservative estimate here. Companies will have more expenses as extreme weather damages assets and disrupts supply chains. They’ll have to invest in reducing emissions. Labor productivity will decline in heat waves. All of that means that stock values are likely to decline. Someone born this year might earn an average of $400,000 less in their retirement account over their lifetime.

Climate action changes the equation

The analysis considers a “business as usual” scenario with emissions continuing on their current path. But taking stronger action and meeting the goals of the Paris climate agreement would cut the total costs for individuals over their lifetime by as much as two-thirds. “There are climate impacts that are baked in already because of the emissions that we’ve already put into the atmosphere, but those costs are much lower,” says Harto.

In a new guide, Consumer Reports recommends changes that consumers can make to cut emissions in their own lives, including adding heat pumps or solar panels at home. (The organization also advocates for stronger climate policy, recognizing that there’s a limit to what individuals can accomplish on their own.) “Many of these solutions are really win-win for consumers and the climate,” Harto says. “They can save money in the short term while reducing emissions in the long term.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.