The global construction sector emits approximately one-third of total CO2 emissions, an unsustainable number, particularly as the built environment is expected to double over the next 30 years.

Innovations in the field range from modular construction to recycled steel and low-emission glass—with one ecological alternative making notable headway: “mycotecture,” or architecture that incorporates mycelium, the root-like structures from which mushrooms grow.

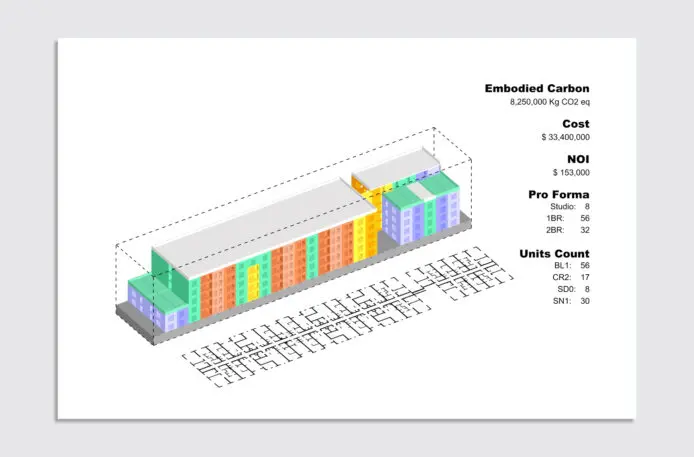

The Phoenix, a 300-unit affordable housing complex in Oakland, California, is pushing the integration of fungi-based infrastructure out of the potential-solutions category and into the realm of active practices. The core of these buildings, which will soon open to residents, will be made from mycelium composite panels, with the exterior being a fiberglass cladding that can resist weathering, and the remaining infrastructure being brick.

It’s just one of several projects around the world that are relying on mycelium as a key component to replace polystyrene foam and other polymers and plastics. “The big thing we’ve done here is replace the filler, which goes in all the facades,” said Eben Bayer, CEO of Ecovative, the materials company that provides the custom-engineered mycelium parts for the Phoenix. The outside panel of building facades, as well as the structural core, are typically made from polystyrene.

Mycelium can be integrated into building materials in different ways, including as insulating panels or brick substitutes (though its life span as brick is about 20 years).

While mycotecture, as it’s known, is in its infancy, experts see it as a key step toward decarbonizing the construction industry and making buildings more sustainable.

“Buildings contribute 40% of global carbon emissions,” says David Benjamin, the applied research lead on net-zero buildings at Autodesk Research, the software company behind the Phoenix. “So to solve the global carbon problem, you have to solve the architecture carbon problem.”

He adds that a building’s facade makes up about 20% of the embodied carbon of the entire building, and “represents probably the biggest potential to incorporate carbon-negative materials.” That brings him to mycelium.

“The big-picture question that my group is researching is, how do we drastically reduce the carbon in buildings at the same time that we’re drastically increasing the total number of buildings? We need something that’s better than just 5% efficiency for five years.”

It’s not Benjamin’s first time working with mycelium. He was recognized for a groundbreaking mycotecture project at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2014, which showed that building with fungi is doable.

Mycelium does a number of things to enhance the sustainability of buildings as well as the quality of a living environment. For one thing, it’s sustainably sourced and is a carbon sink, able to sequester carbon as it grows, rather than being made from extracted oil-based materials. And all of this can be done at the same price while meeting the required fire and building codes.

It’s also nontoxic, with natural soundproofing and insulation qualities, creating a quieter living environment for inhabitants, and one that requires less heating and cooling to maintain a comfortable temperature.

But despite all the material has to offer, its usage is not widespread.

“The biggest challenges of using mycelium in architecture right now are basically strength and durability,” Benjamin says.

To combat these issues, the Phoenix incorporates fiber-reinforced polymer into the mycelium composite. And while mycelium has only select applications now, Benjamin hopes that in another 10 years it will be used much more broadly for construction needs.

To get there, a lot more testing and engineering is necessary, particularly around how organic materials can be combined with mycelium to have a wider range of uses.

In the meantime, the material is lightweight, inexpensive, and super sustainable, so it can be used for things like insulation or in ceiling panels that don’t necessarily need to be strong or durable.

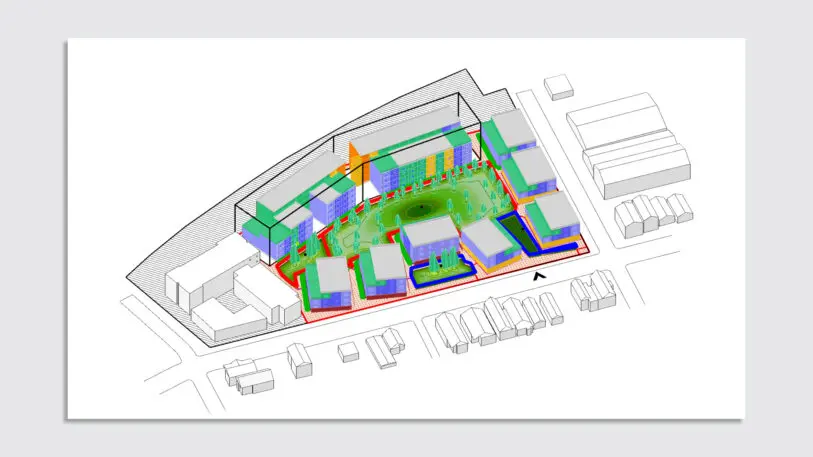

Benjamin also says software infrastructure is integral for mycelium projects to play a leading role in the industry.

“It’s got to be part of a software workflow that will allow other architects and professionals on other projects to use it as readily as they’re using some other more standard materials,” Benjamin said.

Another mycotecture project is being developed in Namibia, where a company called MycoHab recently finished building its first house, with plans to build the next two to three in 2024. This project is unique in that it will add housing while also dealing with an invasive species—the blackthorn encroacher bush—which is choking the country’s water supply. The development will use the material as the substrate.

The next three to five years are critical to the reduction of emissions in the architecture industry. And the speed of mycelium innovation is paralleling that dire need.

“There are a lot of things to combine with mycelium that are natural and organic,” Benjamin says. “So it’s probably only a matter of another maybe 10 years before we can start dialing in the properties of mycelium to be as strong, durable, and flexible as we need by just investing in more tests, more engineering.”

The Phoenix, which broke ground in April and is expected to open next year, is intended as a blueprint for mycelium housing projects that can be replicated and scaled. Autodesk plans to share access to the systems it’s designing for these projects.

“The goal of the project,” Benjamin says, “is to demonstrate the first of its current application, but then make it available for others to use in the future.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.