Graylin Presbury stands under a lone tree on the eastern bank of the Anacostia River looking out at the water that separates D.C.’s poorest wards from its wealthiest. There’s a long list of economic and social disparities between the neighborhoods that flank the two sides of the river.

The residents of the neighborhoods around Anacostia, on the east side, are 92% African American with a median income of about $47,000. Life expectancy is 63.2 years, nearly 15 years lower than the national average and two or three decades lower than some neighborhoods west of the river. Home values are $400,000 less than the rest of the city, and families lack access to affordable, nutritious food. While there are approximately 13 grocery stores in a single neighborhood across the river serving 82,000 residents, east of the river there are three supermarkets serving 150,000 people.

These inequities, and dozens more, have been decades in the making. As federal policies barring Black Americans from credit and financing took root and highways were built through neighborhoods, divisions between the east side of the river and the rest of the District grew.

But there’s hope that a new pedestrian-only bridge park connecting the two sides with recreational space and educational and entertainment hubs will start to change things. “I’m very optimistic,” says Presbury.

The genesis

The project began as an “improbable proposal,” more than 10 years ago, says Scott Kratz, head of the 11th Street Bridge Park project who lives west of the river.

Initially inspired by the High Line, the New York City park that transformed a defunct elevated railway into a lush pedestrian space, Katz quickly realized that D.C.’s park, which will use abandoned bridge infrastructure, needed to “do better.” Since it first opened in 2009, the High Line has become a poster child for what’s been dubbed “eco-gentrification”—beautification that displaces residents as rents and property values soar and wealthy residents migrate in.

Kratz wanted to avoid that. Even before he and his team engaged with a single architect, he reached out to people on the east side: commissioners, business owners, civic associations, faith leaders. “In essence, sort of asking for permission from the community; it was really critical,” he says, since those residents had “long been excluded from the city’s economic progress.”

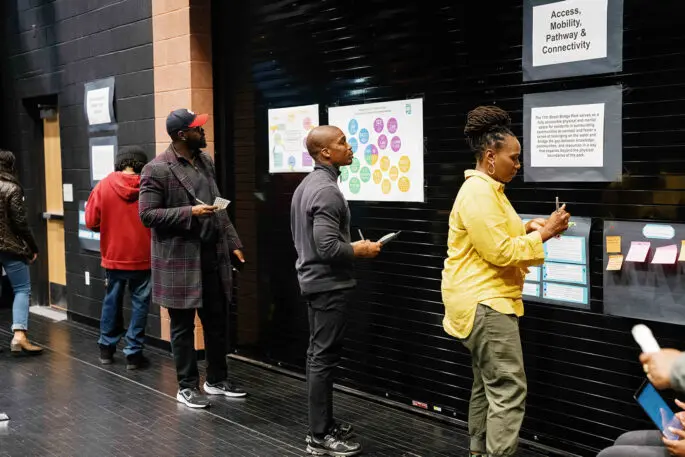

Soon, the talks with community leaders grew into larger community meetings. Since 2012, Kratz and his team have hosted more than 1,000 meetings with residents from both sides of the river (“We stopped counting after 1,000,” he says) to understand what community members wanted out of the project and to find ways to limit displacement.

Presbury, who has owned his home for nearly 40 years, joined many of the meetings Kratz hosted, both as president of the Fairlawn Citizens Association and as a member of the community. Given the history of development, like many in his neighborhood, Presbury was skeptical when he first heard about the bridge park that would connect historic Anacostia with Capitol Hill. I heard people say, ‘It’s not for us,’” he says.

Slowly, the concerns began to dissipate. “Once those meetings started to talk about what we could do together, I believe that was the beginning of a realization that this would be different,” says Presbury. “Finally, it’s not just about developers making money,” he says, adding that it felt like he and his neighbors were really being heard. Further, Presbury learned about the equitable development model built into the bridge project. “I can recall growing up wanting equality. But this was equitable development,” something he says he’d never heard of before.

The equitable development model

One of the most important ideas behind the project was to make sure that the Black community east of the river benefited from the added value that the park would bring. For Kratz, that meant investing early and intentionally on tangible programs for both residents and businesses: finding ways to limit displacement by turning residents who were currently renting into homeowners and helping small business owners buy the properties that housed their stores.

In one of his early community meetings, Kratz met the Rev. Jim Dickerson, founder of Manna, a nonprofit that helps lower-income residents find a path to long-term homeownership. At the time, the group was working west of the river; but, by 2016, Manna teamed up with the 11th Street Bridge Park Project and kicked off a new, monthly program: the Ward 8 Home Buyers Club, based east of the river. With grants from a variety of sources, including the Kresge Foundation, PNC Bank, and Kaiser Permanente, $150,000 has been raised to run a program that helps demystify the home-buying process for people who are likely first in their families to ever buy a home.

The program provides information about down payments, closing costs, inspections, and insurance; additionally, it helps members apply for complicated government grants, including D.C.’s Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP). Of the hundreds of graduates so far, the homebuyers club has tuned 130 renters into owners. Additionally, Kratz and his team found investors to help with down payments and closing costs. At Kratz’s urging, GEICO launched a pilot program offering closing cost assistance of $2,500, which has been provided to 25 club graduates; another 25 will receive grants next year. “Purchasing a home just gave stability for my family,” says Sabrina Walls, 42, who lives with her son and was helped by the homebuyers program and grant. Wells also received an HPAP loan, designed to help reach the District’s goal of adding 20,000 new Black homeowners by 2030. Wells says buying her family’s home in March 2021 showed her son “that he can purchase a house” too, she says. “It is [also] something that can possibly be left for him in the future.”’

After renting for eight years, Cindy Alonzo also took advantage of the Home Buyers Club. “It’s a big deal,” she says of the home she purchased, which is larger than the rental she and her family were living in. Alonzo, 39, says the new home is a “foundation for my children. . . . Knowing that they’ll be stable, not worried about finding a place to live or constantly moving is just really important for me.”

There are also 250 permanently affordable units provided by the Douglass Community Land Trust (DCLT) scattered throughout the communities east of the river. The DCLT’s goal is to secure a total of 1,000 permanently affordable units in the next five years.

The equitable development strategy includes a jobs program, too. Already underway, it includes training for residents interested in construction; graduates get first dibs for jobs building the new bridge park. Nearly 300 residents have taken part in the program so far.

Keeping businesses in the community

As executive director of the Anacostia Business Improvement District, Kristina Noell is concerned about retention of small Black-owned businesses, including mom-and-pop shops that have been family-run for decades. “Expansion and growth is important,” says Noell. “We’re in the midst of evolutionary change, but we don’t want to displace with growth.” It’s a balancing act, she says.

Over the last five years, Noell has been working to prepare Black-owned small businesses for the influx of dollars that the bridge park is projected to bring into Anacostia. It’s estimated that there will be 1 million visitors to the bridge park each year; Kratz projects at least 500,000 will visit Anacostia for the first time. Noell wants to make sure commercial rents in mixed-use developments are affordable to new small business owners and give existing business owners the opportunity to buy the buildings that have housed their shops for decades. “If property owners are going to sell their buildings, why not sell to the businesses that are in it,” says Noell. Only 4 of the 105 brick-and-mortar business owners in the BID own the properties that house their shops.

Additionally, $100,000 in cash grants from Prince Charitable Trust and companies like Target and PNC Bank are helping a number of those small businesses. Booz Allen offered a year-long training program for 10 small business owners east of the river helped them implement new strategies, develop websites, and create new marketing and sales campaigns. “I think that it was a really great opportunity for us as businesses to get the support that we needed,” says Anika Hobbs, founder of Neubian Hueman, a boutique that sells African-inspired apparel, accessories, and home decor. “We’re sometimes a community that’s overlooked.” The program was such a success that Booz Allen recently committed to extend the training program to another 10 small business owners and donated $50,000 so the businesses could invest in new technology.

What’s still missing east of the river, says Noell, is what’s going to keep visitors coming and staying—like the amenities offered in the revitalized Capitol Riverfront on the west side of the river: “hotels, a gym, a place just to go and buy tchotchkes.” Over the past 15 years, that area has reaped the rewards of development and become a thriving mixed-use mecca for residents and tourists alike. “If we do not have the amenities that will help drive that foot traffic to the small businesses and the vibrancy of the corridor, folks will come over, they’ll walk through, they’ll do what they can and enjoy what we have because it’s a cool place,” but then they’ll just leave. “We need to make sure that we have that mix,” says Noell.

In total, $86 million has been invested on the equitable development side of the bridge park project. That includes $14 million in charitable donations raised by the bridge park and an investment of $72 million from the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, a federally certified nonprofit that serves low-income communities throughout the U.S.

What the communities wanted

“Even though both sides of the river are very different, we kept hearing the same things,” says Kratz, about what community members wanted the bridge park to provide. The list included environmental education to inspire the next generation of river stewards, a safe place to play, urban agriculture, and access to the river—a critical request from the east side, which didn’t have any access points. Performance space, too, “was the number one idea that really bubbled up from the community, a place that can amplify the voices and culture and history of local residents,” says Kratz. “Eventually, every single programming element came from these meetings.”

In 2014, an international design competition was launched. 81 firms submitted plans, and Netherlands-based design firm OMA and U.S.-based landscape architecture studio Olin were chosen to design the park.

Salvaged piers from a torn down vehicular bridge originally built in the ’60s (and replaced in 2012) will be repurposed as the base of the bridge. On the east side of the river, the bridge park will rise up from the Anacostia/Fairlawn neighborhood. On the west side, the bridge will land in the Capitol Hill/Navy Yard neighborhood and connect with the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail and into the newly developed Capitol Riverfront.

The Great Lawn that rises 140 feet into the air will allow for views of the U.S. Capitol Building and the Washington Monument, which are typically blocked by the Navy Yard. The central “Anaquash Plaza” will host farmers markets and other events including work fairs. The name honors the Native American inhabitants who lived in the region before European settlers pushed them out; the Nacotchtank word anaquash means village trading center. On the first level, the Community Front Porch will include a covered café and gathering space; Hammock Grove will have 170 native trees and 10 hammocks inspired by different community leaders.

On the east side of the bridge, the play area, called “Mussel Beach” is a nod to the environmental work being done with fresh water mollusks that are helping to clean the Anacostia River by filtering out pollutants; and the Environmental Education Center will host programs run by the Anacostia Watershed Society. Just off the bridge, there will be an amphitheater, an urban farm, and a kayak and canoe launch. The entire landscape will be punctuated by public art including sculptures and murals.

The 11th Street Bridge Park project is expected to break ground in the first quarter of 2024 at a cost of $92 million, including $45 million funded by the District. The rest has been raised by the bridge park, an arm of Building Bridges Across the River. To date, they’re just $8.5 million shy of the total needed to break ground, and they’re seeking an additional $10 million in capital reserves for the park’s ongoing operations.

The 11th Street Bridge Park project is having a “ripple” effect across the country, says Kratz, as other cities are looking to bring disparate urban centers together through nature. San Francisco’s India Basin Park and the Los Angles River revitalization effort, including Taylor Yards, are following the D.C. park’s equitable development playbook to engage their own residents to create anti-displacement strategies.

“The inclusion model is about doing things in a different way, a better way,” says Kratz. “Investing early and intentionally with local residents at the center of the decision-making process can help ensure that they’re the ones who can benefit.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.