Five years ago, before the catastrophic Camp Fire burned through Paradise, California, destroying 11,000 homes and killing 85 people, driving through the small town looked like driving through a pine grove. “There were so many trees that you really couldn’t see very far,” says Collette Curtis, the city’s recovery and economic director. “It really was like being in a forest.”

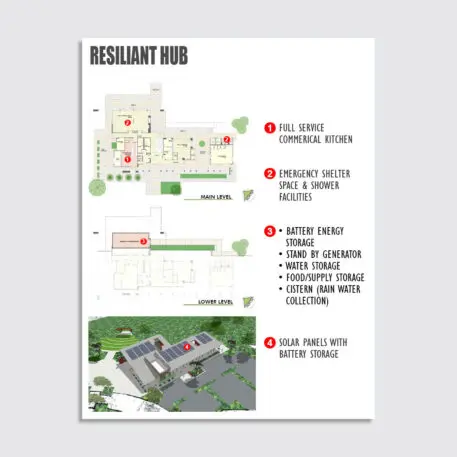

Today, it looks very different. Some newly built houses are now visible on lots that were previously hidden by trees, with ample space around the homes to help prevent the spread of flames. (Without the thicket of trees, it’s also so much sunnier that some homes have solar panels for the first time.) The local parks department, which bought some land at the edge of town from residents who decided to move away, is considering the idea of a creating a buffer park that could help protect the town in the case of a future fire. A park under construction in a neighboring town will double as a gathering space in an emergency, with showers and its own power source in the case of an outage.

The wildfire was the world’s costliest disaster in 2018, and the deadliest fire in California history. It started when a faulty transmission line sparked vegetation that was dry after six years of drought, and it spread far within hours, eventually burning an area larger than Chicago. After the tragedy, some survivors decided to move away. But the area is also rebuilding relatively quickly: For the past two years, Paradise has been the fastest-growing community in California.

That’s not to say that rebuilding has been easy. Some families are still living in RVs on their land because they haven’t been able to start construction. Many residents originally moved to Paradise, which is around 90 miles north of Sacramento, because it was more affordable than other parts of the state, and the cost of rebuilding under the current building code—with strict state requirements for areas at high risk of wildfires—can be prohibitively expensive. It also took time before building could happen, while government agencies removed nearly 100,000 burned trees from the town and infrastructure was inspected and replaced. Some people didn’t have adequate insurance; others have struggled to get the money that they were owed or find contractors to do the work. Settlement money from PG&E, the utility responsible for starting the fire, has been slowly trickling out.

The city set up a Building Resiliency Center where people could get hands-on help. “We also hired what we called rebuild advocates,” says Curtis. “Really, their entire job was to sit with people who felt that they needed some extra help in the building process, because it’s overwhelming—there’s a lot of steps. There’s a lot of professionals that you need to bring in. These rebuild advocates would sit with people for as much time as they needed to help them fill out the paperwork, help them navigate their own insurance, or help them find grants that were available.”

The city also hired new staff to handle permitting. Before the fire, Curtis says, there might have been 10 new homes built in the city each year. Now there are between 500 and 600. And, critically, the city has offered guidance to make new houses more resilient in a fire. New city rules, based on recommendations from the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, require that nothing combustible can be within five feet of the home, from trees and shrubs to wood chips. Some residents have also chosen to rebuild with particularly fire-resistant materials, like concrete.

On the edges of town, the parks department is beginning to manage land differently to help act as another line of defense if a fire approaches the community. “When people hear ‘firebreak’ or ‘fireline,’ they think it’s an area devoid of vegetation,” says Dan Efseaff, the Paradise Recreation and Park District manager. “What we’re looking at is managing it in a healthy forest approach. So they would be shaded fire breaks that have low fuels, and these are fire-adapted landscapes.” If a fire happened in the wild areas nearby, it’s a zone that firefighters could also use to help keep approaching flames away from homes.

Designers from SWA Group worked with town leaders to develop the concept of surrounding Paradise with defensible space. Now, the parks department plans to hire a technical advisor who can help study the idea in more detail, while the team works to manage the land that it has already acquired. It’s taken years to clear out most dead and dying trees, one crucial step in preventing out-of-control fires.

Parks managers are also trying to help more oak trees grow. The area used to be dominated by oaks, a more fire-resistant tree, rather than pines. In another part of the nearby foothills, Butte County Resource Conservation District and partners like the nonprofit American Forests have also been encouraging oak seedlings in the aftermath of the fire.

“We did plant a few baby conifer trees that were selected from genetics that are likely to be climate resilient and drought tolerant, and they’re doing okay,” says Wolfy Rougle, conservation project manager at Butte County Resource Conservation District. “But the stars are really the oaks. We focused on the oaks that were naturally resprouting, and just trying to give them the best headstart that we could.” The team has cleared out brush to help the trees grow, and pruned trees with multiple sprouts so they can develop a thick trunk more quickly.

Some of the landscape is starting to look a little more like it did before European settlers moved to the area and started planting pines to harvest in the timber industry, with oaks interspersed on rolling, grassy hills. “Oaks were kind of drowned out by the conifers, and the identity of that community became more of a conifer forest identity,” says Rougle. Now, at least in the areas where restoration is happening, oaks can begin to dominate again. They’re more likely to be resilient as climate change makes the area hotter and drier, and they’re less likely to burn.

All of these approaches—along with improvements in forest management around the region—can potentially help reduce the risk of another catastrophic fire. “There’s no completely risk-free strategy in some of these wild-urban interfaces,” says Brett Milligan, a professor of landscape architecture at UC Davis and coauthor of Design by Fire, a book that looks at how communities in fire-prone areas around the world are adapting to become more resilient. Paradise still faces challenges, including the fact that it needs better evacuation routes.

It’s arguable that building in some fire-prone places is too dangerous. In San Diego County, a development in an area with very high fire risk was stopped after an environmental lawsuit (in the ruling, the judge cited the fact that the developers hadn’t analyzed the fire risk). But it’s easy to understand why families who lived in Paradise for generations would want to stay, and why others would be drawn there. It still sits in a beautiful landscape. And it’s not uniquely risky: One study found that one in every 12 homes in California is at high risk of destruction from wildfire. And while the average house in California costs well over $800,000, it’s possible to buy a new house in Paradise for less than half of that, or an empty lot for as little as $25,000.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.