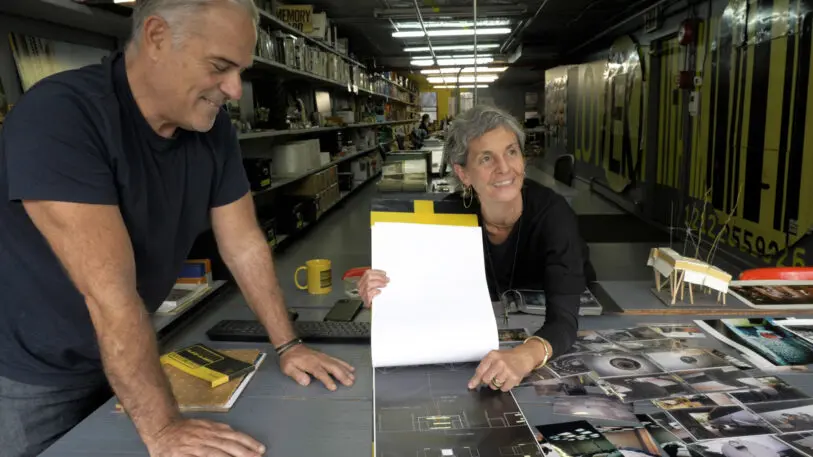

A collection of slide-projector film cards sit on LOT-EK cofounder Ada Tolla’s desk, rich with images of the first shipping container depot she and her partner, Giuseppe Lignano, found themselves in unexpectedly one Sunday in New Jersey 30 years ago.

“It felt like we were in a magic city,” she recalls in We Start With the Things We Find, the upcoming documentary directed by Thomas Piper that chronicles the work of Tolla and Lignano designing structures with the hulking steel boxes. “We fell in love with this object,” she says. “We thought, This is it: We need to take this object and make architecture out of it.”

Across the decades spanning the shipping container’s short history—it was invented in the 1950s—the world has amassed more than 180 million of them and the global market is expected to more than double by 2028. In the film, Tolla and Lignano explore the industry’s lack of visibility with Leonardo Bonanni, the founder and CEO of Sourcemap, a company that aims to solve it. Given their relative lack of traceability, there’s little awareness of exactly how many containers exist, what contents are in transit, and where they are at any given time.

The most significant ecological challenge, Lignano maintains, is their accumulation. Some estimates report that only 10% to 15% are being reused. For more than a decade, architects have viewed this as an opportunity to create affordable, sustainable housing—for families, students, and those facing homelessness—as well as for disaster relief.

What began as Piper’s inspiration to document the creation of LOT-EK’s first home, and soon the architects’ journey, evolved into a simultaneous exploration of the shipping container industry and its environmental impact. The newfound collective awareness of the containers as supply chain issues arose during the COVID-19 pandemic was a further impetus to go deeper.

“It was an opportunity to think: There’s much more to this than just the objects,” Piper reflects ahead of the documentary’s North America premiere on October 25th in New York City. “There’s a whole world and questions behind them: What are we shipping all around the world? Why do we need all these things? Hopefully, that part of the story goes from, ‘Look how thrilling this thing is,’ to a bigger understanding of everything the object represents.”

Tolla poses one of the film’s most compelling questions overlaid on their journey on a boat carrying 6,589 shipping containers: “We are not philosophers. We are doers. So, we have to make things. How do we make things that can both celebrate and tell the tragedy of this story?”

In conversation with Fast Company, she invokes living in these storied walls and invites us to consider whether we can become intimate with our role in their narrative in a way that can still be beautiful.

“It’s a beauty that questions the idea of beauty,” Tolla explains. “They carry within them this heft and weight of what they mean. You see it. You need to acknowledge it. You need to think about the fact that it is becoming more and more omnipresent. Every time we click ‘buy’ we are calling it in. We have a shared responsibility in that.”

Lignano emphasizes intimacy as an essential part of the process with Tolla, while she admits that “the work aims more to pose questions rather than to answer them.” These questions are woven through the architects’ interactive style and inspire their exploration of new opportunities in sustainable design. This all began in the early 1990s when they started upcycling industrial objects—from sinks to street lights—transforming them into works that have been showcased in New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, and the Guggenheim, among others.

“It’s the idea of working with existing things and interacting with the world around us with a different mind frame and curiosity,” Lignano says. “We want to discover resources that are not even forgotten or untapped but that we’re ashamed of. We don’t want to look at all of the things that we create for necessity, but also for greed and imbalances in our civilization. In order to change things from the inside, you can’t stay on the surface. You have to go inside and really question how things are made.”

This depth is what Tolla expresses in the film when she shares her own intention, asking: Can you be even more honest with the things that you do? Can you do even less? “Our work fails to be pretty,” she adds. “It’s good or bad, fantastic or horrifying. It always has that edge where it’s caught between these extremes.” And that, she says, is precisely the point: “It’s an invitation to interact with things differently—to let things interact with each other and find the beauty in that conversation.”

LOT-EK’s projects embrace the nature of this interaction to overcome design challenges in container architecture, such as their narrow dimensions and need for insulation. While removing portions of the walls and stacking them enables their expansion as homes and, more relevantly, spaces like schools and nonprofit centers, equally inspiring is the architects’ vision of positioning the containers themselves as design structures.

Lignano illustrates stacking the containers like “giant bricks,” overlaying two of the container walls as a roof, and then connecting them to create a space in between, like a museum hall, that can be at least 40 feet wide. The containers are then used for offices, storage, mechanical systems, and more.

Still, Lignano asserts, “the only sustainable building is the building that is not built.” Despite the generativity of upcycling, the rise of container architecture faces its own set of sustainability questions and challenges to determine whether it’s a net positive environmentally.

“When we think about the bad environmental impact that buildings have on our planet, we think about energy consumption, meaning what the building does once it’s built, like lighting and air-conditioning,” Lignano says. “The biggest impact from a sustainability perspective is the actual construction of the building; 40% of humans’ carbon footprint is from the construction industry.”

LOT-EK is inspired by Buro Happold’s new software, which enables architects to calculate a project’s carbon footprint by taking into account their materials. The firm continues to seek a partner who is open to using it. Tolla and Lignano also aim to upcycle their own materials by saving or repurposing them within projects, such as the structural columns, furniture, and sculptures they created at their live-work property, Drivelines.

Communal living is among the film’s and LOT-EK’s most exciting invitations, illuminated by a question Lignano poses during our interview: How can we transform the way we design spaces to be less compartmentalized and allow people to integrate their lives with each other?

“The thing we question the most is the status quo,” he says. “The architectural world is dominated by practices that not only aren’t the best for the environment, but in terms of helping people live their best lives. . . . Sustainability is not only at an environmental level. It’s at a human and community level.”

Drivelines—the 75,000-square-foot residential and retail property LOT-EK designed in Johannesburg in 2017—is an answer to that question. As part of an effort to reinvigorate the city, it’s the first post-apartheid residential building constructed adjacent to downtown. The team transformed 141 shipping containers into 300- to 600-square-foot studio apartments—105 of them—for single residents or couples. Lignano anticipates 100 to 200 people occupying the spaces, which are connected by courtyards and shared areas to streamline community building.

Given the collective positive reception, the team anticipated that it would be a proof of concept. Yet while they’re energized by collaborations with nonprofits and partners who similarly seek to inspire connection, they’re hopeful the film will be an impetus for more large-scale communal spaces. “Value is not just square footage,” Tolla says. “A community space has value—not only spatial value, actual value—because it’s the quality of the space that changes.”

The eight years Piper spent with Tolla and Lignano filming We Start With the Things We Find resulted in “a humanist essay not only about a new kind of design thinking, but a new design for life,” as architect and professor Thomas de Monchaux articulates in its description. Piper’s aspiration is that seeing things differently will spark awakening and action for audiences on an individual level.

“The basis of art is finding something that other people don’t see and making it visible,” Piper says. For her part, Tolla insists, “The idea of seeing differently is very important. For us, it’s a practice. The idea is that you don’t see things for what they’ve been used as. You see them through the eyes of what they can become.”

In the film, Lignano describes disposable culture as a “losing proposition,” not solely environmentally and socially but also creatively, stating that “the intelligence behind making the most of what you have is within us. It’s something that can propel our civilization in a different way.”

He cites Wasteocene author Marco Armiero’s philosophy by asking: “What is waste?” as an immediate place to start. “It brings the agency to us,” Lignano explains. “It’s not the industry making plastic bottles that is making waste. When you throw that bottle into a waste bin, you have decided that it is waste. It’s a way of humanity asking ourselves that question in a radically different way. We’re never going to stop doing or making things. So how do you always have that question in the back of your mind?”

Piper adds, “Architecture is prone to grandiosity. With Ada and Giuseppe, it feels much more pure. They live the idea that we should use these things that already exist. A new shiny glass building is not inherently better than a building made out of rusted shipping containers—it’s not one or the other. The direct application of their ideas and work is in design and architecture, but what underlies it is a way we could all live.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.