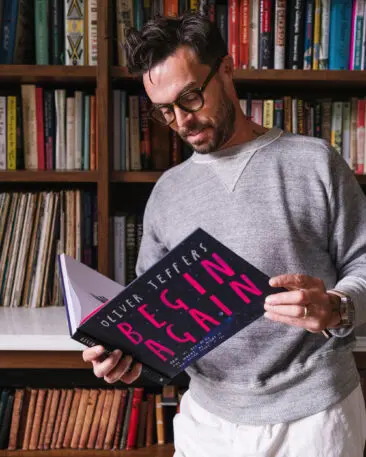

If you’re a parent, there’s a good chance you know the artist Oliver Jeffers. He illustrated the wildly popular children’s book, The Day the Crayons Quit, and he’s also written and illustrated several of his own books, including the best-seller, Here We Are: Notes For Living on Planet Earth. His aesthetic is spare and minimal; he sometimes includes pages of images without text, giving the readers the space to narrate the story in their own way.

But as a fine artist, Jeffers also creates art directed toward adults. His work spans mediums, from sculpture to paintings to illustrations. But if you look closely, you’ll see themes consistently pop up across all of his work. He’s interested in what it will take to solve the climate crisis; his answer always comes back to collective action. In other words, we have the scientific tools to avert a climate disaster. What we need is to work collaboratively to bring about the solutions.

Jeffers brings together his two practices—picture books for children and fine art for adults—in a new book called Begin Again. In the book, Jeffers explores what it will take for humanity to create a single narrative about who we are, so we can work together to address the crisis that looms before us. The book is philosophical and existential, delving into our origins as a species and how meaningless national boundaries are.

I sat down with Jeffers to discuss his artistic practice and why he believes art is a powerful tool as we work to address the enormous problems before us.

Fast Company: What made you decide to write a picture book for adults?

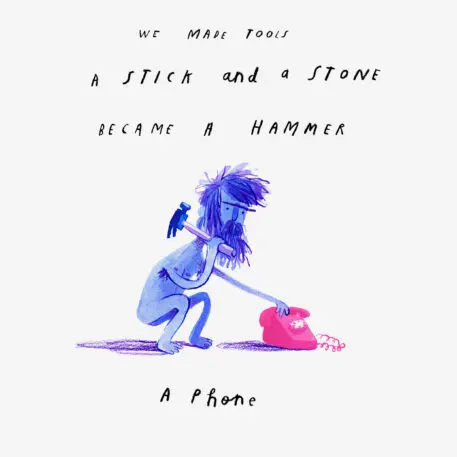

Oliver Jeffers: We read images in a different way than we read words. So when we combine these ingredients, it forms something that is potentially more powerful than just seeing the same content in a sentence or paragraph.

I’ve always liked the structure of a picture book. It forces you to distill your ideas down into their most simple form. And with this book, I am able to get into some relatively complicated territory. That’s why it is not a kid’s book per se, in that you would not necessarily read it to your child at bedtime. But I can see it being a platform for a conversation between parents and children about issues that are at large in the world today.

Fundamentally, the book is about remembering that the good feelings that you have in your life ultimately come from the existence of other people. Life is about this co-creative, collective experience. It’s not all about you or what you can get away with; you ultimately feel better when you understand your role in moving the needle in a positive direction.

FC: One thread throughout your books, including your children’s books, is the notion that there are big problems in the world, but that it takes collective action to bring about change.

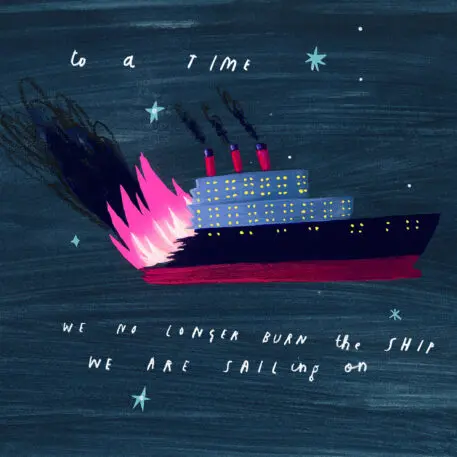

OJ: That’s a correct observation. For all the problems that exist in the world—including pandemics and the climate crisis—we already have solutions. The thing that needs to be addressed is creating a sense of a single, cohesive movement. Germs and weather do not need passports. They affect everyone in the world, regardless of country.

Part of the realization of this book is that the climate crisis and the political crisis are connected. Conflict and disunity are multipliers, exacerbating the problems in our world today. What’s ultimately happening is that we’re writing competing stories that have the effect of canceling each other out. We keep thinking about how the problem affects me and how I can personally benefit from a solution. It’s a futile way of thinking because what happens to one person, one community, one country, will happen to all of us.

What we should be doing is creating a single story about what to do. When Frank White, the NASA engineer, saw our planet from space, it immediately became clear to him that we need to act as one species with a single future, or we’re not going to survive.

FC: This book begins with the notion of the the Overview Effect, which is something that happens to astronauts see the Earth from outer space and it fundamentally alters their thinking. Why is that so compelling to you?

OJ: It’s been a consistent fascination of mine for some time. It started when my son was born. There was this comedy of explaining the world to somebody who was a completely blank canvas, an unmolded ball of clay.

Then, the gravity of that moment hit. We all arrive on Earth as unwritten stories, and he will have to write his. The sheer responsibility and potential power of that is enormous. It’s like what Mary Oliver wrote: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” It’s such a basic question but the truth is that we only get one crack at this business of being alive.

FC: How do you navigate giving children a sense that they can change the world and help fix these problems, while also ensuring that they aren’t weighed down by that responsibility?

OJ: It’s a real concern. You only get one brief moment in your life that is childhood. So I think it’s important not to be lecturing our kids all the time about everything that is wrong with the world. But when they’re curious, I think we can answer them as directly and simply as possible.

And I think, with children, it comes down to teaching them simple things, like being nice to people and thinking about the purchases we make and how we vote. I personally think the greatest thing we can do for the environment is not over-consume. And this is something we can teach our kids early. But you know, I’m kind of just making it up as I go along, like everyone else.

FC: These lessons are equally valuable for adults, which is why I think it makes sense that Begin Again is for them as well. How do you convince people who are naysayers?

OJ: I’ve found that you’ll never convince anybody to change their mind by telling them that they’re wrong. A very important notion in the book is that just by living, acting, and telling more interesting stories, you are ringing a much bigger bell that can create potential action.

And I also think it’s important to also remember that while the world is truly falling apart, there has also never been a better time for human beings to be alive on Earth. Think about all of the scientific advancement we’ve made and how good our quality of life is, compared to a thousand years ago, five hundred years ago, or even a hundred years ago. It is easy to see everything that’s wrong, but it is also a matter of having conversations about what we can do to make things better, rather than just focusing on the problems.

FC: It’s clear from your work that you believe art can be a force for change. Why do you believe that?

I was at the TED Climate Countdown [a conference that helps accelerate climate solutions] running this workshop. I was an artist among scientists. And I think I managed to convince these scientists that art is as important as science. Because science helps us figure out how to do things, how to solve problems. But art addresses the question of why. Art allows you to change the filter through which you look at the world, and in doing so changing the way you move through it.

I think it’s unfortunate that we see art and storytelling as distractions from the real work. Because fundamentally, stories are a core part of who we are and why we do anything.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.