It’s the basic attention to detail that stands out on a Brightline train: the legroom and plush leather seats; the designated places to store bikes, rest phones, and hang jackets; the free Wi-Fi and charging ports; the clean bathrooms designed to be hands-free.

These amenities felt like a dose of luxury after nine days of road travel in Florida in May, when I faced the typical traffic jams and torrential rain. So on my last day, after returning my rental, a simple train ride from Fort Lauderdale to Miami was a treat. Only a swift half hour trip, I was just getting settled into my snack tray and mimosa when it was already time to disembark.

It felt like a luxury, because in America, it is. Brightline’s Florida service is the only private passenger rail service in the U.S. Though it’s not technically high-speed, its next project, from L.A. to Vegas, will be. The company has steered past some of the biggest hurdles that rail ventures have faced for decades, and if it’s successful, the new line could inspire other companies to follow suit, toward finally building a high-speed network around America. But it remains to be seen if American customers, so used to traveling by car, will eagerly adopt mass transit.

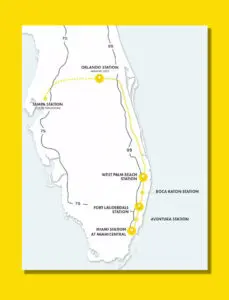

Since 2018, Brightline’s Florida service has operated from West Palm Beach, south to Downtown Miami, taking the 70-mile route in 75 minutes, passing through hubs like Boca Raton and Fort Lauderdale. In September, a long-awaited route will open from Miami to Orlando, linking the beaches and bustle to the theme park capital and the home of Mickey Mouse. Florida attracts more than 130 million tourists a year, many of whom are international and used to train travel. And for convenience, the Orlando station will be inside the airport’s new terminal.

There’s also an increasing commuter base, with about 1,500 people traveling from West Palm Beach to Miami about 15 to 20 times per month, according to Brightline CEO Mike Reininger. For its tourism and business opportunities, as well as its massive population, Florida was the natural state for Brightline to fulfill its “proof of concept” of a rail alternative. “It makes sense to fish where the fish are,” Reininger says.

The route allowed the company to evade what Reininger views as the two biggest hurdles rail companies face in the U.S. Brightline built directly along existing highway corridors, avoiding the need to purchase new land. The alternative is usually a jigsaw puzzle of patching pieces of land together from different owners. “One holdout and you have a gap,” he says. “If you have a gap, you don’t have a right of way.” And, because it’s already a functioning corridor, the company has secured the necessary environmental permits, sidestepping another major holdup.

The area’s alternative transport options are onerous. Weather and traffic can turn a two-hour drive into four, and South Florida roads are notoriously dangerous. “I-95 is one of the most challenging drives anywhere in the United States,” Reininger says. According to data, a portion of I-95 in Fort Lauderdale is the deadliest one-mile interstate stretch in the country.

But even though the line is a boon to the area, a high speed train would be key to truly expediting those journeys. High-speed rail is generally agreed to be more than 155 mph, but the service in Florida doesn’t hit the mark, traveling at 79 mph in South Florida, and 125 to Orlando. “It’s too slow,” says Harry Teng, a railroad engineering professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “It’s not high-speed rail at all.” (My Fort Lauderdale-to-Miami trip was 35 minutes, which can be done in about the same amount of time on a good road day.)

In Florida, that may be fine, because the unique conditions make driving so hard. “The speed matters a lot,” says Seth Moulton, a Democratic congressman in Massachusetts. “But because traffic is so bad in southern Florida, they’ve been able to get a good number of passengers going at very conventional speeds.” In other markets, that might not cut it.

High speeds, low funding

Out west, the ride will be fast. If Florida is the company’s proof of concept, Brightline West is the prototype. It’ll similarly connect two popular hubs, Los Angeles and the adult Disney, Las Vegas. The 100%-electric train, running at starting speeds of 186 mph, is due for completion in late 2027 or early 2028, in time for the L.A. Olympics. It’s a much bigger project, but again runs along the existing I-15 corridor.

The route is a historical one. In the 1970s, Amtrak offered a weekend service between the two cities that came to be known as the Crapshooters Express, or the Las Vegas Fun Train, at times with live music, poker, and booze.

There’s still demand for that route, says Teng, who’s also the Commissioner of the Nevada High Speed Rail Authority, where he’s tasked with monitoring and facilitating the project’s progress. He notes that on weekends, cars pile up along the whole stretch, and he estimates that rail could divert 60% to 70% of that traffic. “This is the demand that makes this high-speed rail profitable,” he says.

Moulton, the congressman, has been a long-time proponent of high-speed rail, particularly noting its climate benefits: Train travel produces 83% fewer carbon emissions than driving. He says Brightline West is promising, and hopes people don’t view it as a one-off just because it’s Vegas, with its own unique market. “There are a lot of corridors all over America that have similar characteristics,” he says, “whether or not they have a Las Vegas at one end.”

Before joining Congress, Moulton worked as managing director of Texas Central, a company that has aimed since 2009 to connect Dallas and Houston with a high-speed train. But, like several other rail projects, it has encountered the usual obstacles: land purchasing and regulation. “I think we should have environmental regulation,” Moulton says. “But when environmental regulation impedes projects that are fundamentally very good for the environment, that’s pretty counterproductive.”

Moulton believes private businesses are best equipped to lead the charge on rail, because they typically overcome hurdles faster than the public sector, and provide better experiences, thanks to the “innovative and competitive culture of the private sector . . . which has been elusive for Amtrak.”

Amtrak is the state-owned enterprise that has operated passenger rail service since Congress established it in 1970. It was designed to financially support private rail companies at a time when ridership had declined and companies had reduced the number of trains in service from 9,000 to 450 between 1950 and 1970.

But over the years, Amtrak hasn’t been well funded, leading to delayed services at slow speeds; the Chicago-to-Seattle route, at 46 hours, takes 50% longer than driving. Trains compete with private freight trains on the same tracks, which take priority. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill that passed in 2021 granted the biggest chunk of money to Amtrak since its founding—$66 billion—to bolster tunnels and fix crumbling bridges, largely in the Northeast, where the majority of its ridership takes place. Parts of its Acela route are already high-speed, reaching up to 150 mph, and it has plans use some separate funding to accelerate that to 160 mph in New Jersey.

But Moulton says even private rail companies need public funding, because the government heavily subsidizes the competition—road and air. Rail needs the same capital to have a fair shot. “A relatively minor commitment would leverage a tremendous amount of private-sector capital, and you would get [projects] done,” he says. “This doesn’t have to be just more taxes. It has to be a better use of taxpayer resources.”

Brightline is hoping to dig into some of these public resources. The entire Florida project, which cost $6 billion, was funded via private equity and municipal bonds. But Brightline West will cost twice that. The company plans to finance it in mostly the same way, but has also applied for a Federal-State Partnership Program grant of $3.75 billion, as part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill. If all goes to plan, they’re in a position to break ground by the end of the year.

Short-term snags, long-term goals

Even for a company that has navigated the traditional obstacles, there have been some bumps along the ride. Brightline West won’t go directly to Downtown Los Angeles, rather Rancho Cucamonga, 40 miles east, leaving riders headed for the city with the choice of an extra commuter train journey, or figuring out a car ride. (Several other connecting transit options are also planned in advance of the Olympics.) And after complaints from conservation groups that the track would cut across wildlife habitats, the company has agreed to build a number of crossings for bighorn sheep, and fencing to protect desert tortoises.

Most pressingly, since testing began in 2017, there have been at least 88 reported deaths connected to the South Florida line. A Brightline spokesperson says none were due to operations, rather mostly related to drivers circumventing safety devices, while half have been suicides. In partnership with state and federal departments of transportation, Brightline says it has invested millions of dollars toward fencing, landscaping, and crossing gate enhancements.

Then, there’s the challenging task ahead: convincing an American audience, historically attached to the automobile and the freedom it symbolizes, that they should take the train. Unlike the Northeast, where most of Amtrak’s ridership occurs, Brightline’s markets like Florida and California are reliant on cars, and will need some behavior changes.

But that blank slate is a benefit, Reininger says. Consumers don’t have an expectation for train travel, so Brightline is molding a rail experience for novice riders. “We specifically built a product that was meant to appeal to the expectations of an American consumer, who, generally speaking, has very high expectations about everything,” Reininger says. “If you’re starting from zero, you don’t have to undo anything that may have been established.”

Hence: the ride experience with the amenities. On board, there are attendants offering food and beverage service, similar to a plane; at stations, there are stylish bars and lounges for premium passengers. Reininger says the facilities tackle the precise pain points that people say they detest on car rides—such as the “ick factor” of stopping at a roadside McDonald’s to use a restroom. Brightline’s clean, hands-free bathrooms feel infinitely more palatable.

“They’ve got a great experience,” says Wayne Rogers, CEO of Northeast Maglev, another rail company planning to build high-speed rail between Northeastern cities using Japanese electromagnetic tech—initially with a Baltimore-to-D.C. route in 15 minutes.

Brightline is already seeing consumer demand. In the first full year, 2019, they carried about a million people in South Florida, Reininger says. In 2022 year, the first year post-COVID, they carried 1.35 million, a 35% increase in ridership; they’re on track for 2 million this year.

The company is confident that after riding the train once, passengers will repeat rides, and encourage others to try it. That could be a benefit to the other rail projects, not just from Brightline. One day, they could form a larger U.S. network, probably in the form of city pairings around the country: Orlando and Miami; L.A. and Vegas; Dallas and Houston; New York and D.C.; Atlanta and Charlotte; Seattle and Portland.

In that sense, the companies don’t view themselves as direct competitors, rather complementary to each other. “We cheer [Brightline] on everyday,” Rogers says. “We hope they’re successful.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.