Your future house could have a foundation that’s able to store energy from the solar panels on your roof—without the need for separate batteries.

MIT engineers developed the new energy storage technology—a new type of concrete—based on two ancient materials: cement, which has been used for thousands of years, and carbon black, a black powder used as ink for the Dead Sea Scrolls around 2,000 years ago.

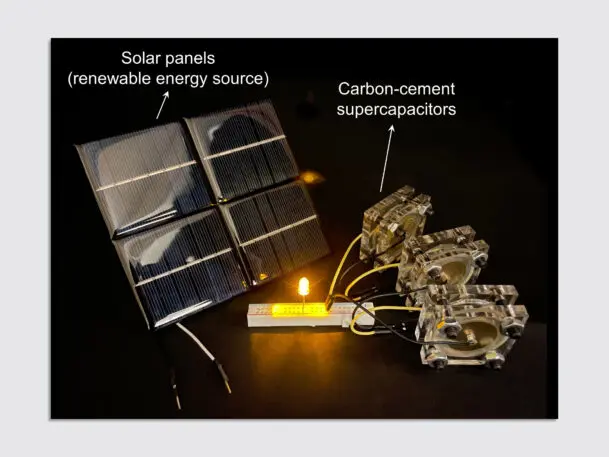

Carbon black conducts electricity, and the engineers discovered that if it’s mixed with cement and water in a specific way, it forms a long, branching network of carbon “wires” as the cement hardens. That turns the material into a supercapacitor, a device that stores an electric charge. “All of a sudden, you have a material which can not only carry load, but it can also store energy,” says Franz-Josef Ulm, a civil engineering professor at MIT and one of the authors of a new study about the tech.

Unlike a battery, which works by converting chemical energy into electrical energy, a capacitor doesn’t degrade over time and lose the ability to hold a charge. (A supercapacitor is a type of capacitor that can hold a very large charge.) A capacitor also doesn’t require the expensive, ethically questionable materials used in lithium-ion batteries like cobalt and lithium. Because carbon black is inexpensive, the researchers say the process would add little to the cost of making concrete. It could be a solution for one of the major challenges in scaling up renewable energy: Since solar and wind power aren’t always available, quickly building more affordable storage is essential in order to pivot away from fossil fuels.

The engineers were inspired to work with cement in part because cement production has a large carbon footprint, and giving it a second purpose supporting renewable energy can make it more sustainable. The process could also be used with newer cement alternatives that reduce the emissions of manufacturing, like a version of Portland cement from the startup Brimstone that’s designed to be carbon negative.

In a house, a foundation made from the material could potentially store as much solar power—connected via cables to the roof—as the house would use in a day. At a wind farm, it could be used at the base of wind turbines. The concrete could also be used to make roads that can charge electric vehicles as they drive. In the new study, the researchers found that the capacitors could be designed to charge slowly, as in a house, or discharge quickly, as in an EV charger.

After testing a small version in the lab, the team now plans to scale up to larger sizes. The first prototype could potentially be ready within 18 months, Ulm says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.