Hello again from Fast Company, and thanks for reading Plugged In, our weekly tech newsletter. I’m global technology editor Harry McCracken, the guy responsible for this thing. If a friend or colleague forwarded this newsletter to you—or you’re reading it on FastCompany.com—you can check out previous issues and sign up to get it yourself every Wednesday morning. I love hearing your feedback and ideas for future editions: Drop me a line at hmccracken@fastcompany.com.

I have this strange hunch you’ve already heard about this week’s biggest Twitter news: Elon Musk, in his infinite wisdom, says he’s in the process of rebranding the service as X. His decision has already inspired vast quantities of takes—such as those my colleague Chris Stokel-Walker rounded up on FastCompany.com—and you can probably survive without another one from me.

So let’s talk about a different topic: the plans behind Musk’s decision to ditch one of the online world’s best-known names in favor of something unrelated and untested. He says that he intends to use his $44 billion purchase as a springboard to create a sprawling platform for everything from video streaming to banking: “The Twitter name does not make sense in that context, so we must bid adieu to the bird,” he, um, tweeted.

Musk calls this Swiss Army knife vision “the everything app.” It’s his name for a class of platforms that already exist and are often called super apps. The best-known example is China’s WeChat, which is the country’s equivalent of Facebook. And a pervasive tool for paying brick-and-mortar merchants. And an app platform unto itself that third-party developers use to offer an array of capabilities for every aspect of life.

Now, China is a distinctly unique market, in ways that helped WeChat attain its super-apphood. (For one thing, the country bans what might otherwise be some of the app’s most formidable rivals.) That hasn’t stopped U.S. companies from envying WeChat’s dominance and striving to emulate its approach. For example, after Meta (née Facebook) split off messaging from the main Facebook app, it went through a period of trying to turn Messenger into a super app, cramming in everything from games to customer service to third-party applets. Remnants of this vision remain intact, but we can take the company’s recent moves to reintegrate Messenger into Facebook as evidence that it wasn’t a spectacular success.

Musk’s ambitions for his platform face several obstacles, ranging from his off-putting behavior to the discordant feel of jumbling (supposed) freedom of speech and money management in one product. But the primary conundrum for Twitter or anyone else trying to build a new super app is that they’d be building it on top of iOS and Android—which are already super apps. Both operating systems make downloading and using third-party apps so simple that users don’t have much incentive to stay within the walls of any single app, regardless of how many features it offers. Why stick with a ho-hum feature built into an app you already use when a best-of-breed alternative is just a couple of taps away?

Apple has also nailed the process of segueing into financial services, a challenge that it’s been chipping away at patiently for two decades. In 2003, the company started selling music downloads, motivating millions of customers to create Apple accounts associated with their credit card information for the first time. Five years later, the App Store became a core element of the iPhone, with Apple processing the payment every time a user bought a piece of software. By the time it launched a credit card in 2019, it seemed like a perfectly logical addition. Same for its recently introduced savings accounts and buy-now-pay-later service.

Apple’s financial-services foray has always offered tangible benefits to the consumers it’s hoped to sign up. By contrast, Twitter seems to be having trouble convincing people to pay for its Twitter Blue premium tier, which doesn’t bode well for its immediate ability to expand into other monetary matters—the kind that would make Musk’s talk of capturing half of all global financial transactions sound like more than an overconfident mega-billionaire’s fantasy.

It’s impossible to cast doubt on Musk’s grandiose intentions without hearing from folks who helpfully point out that the experts scoffed at Tesla and SpaceX, too. So I won’t declare his everything-app strategy to be dead on arrival. Actually, I’d love to see it show signs of life. If nothing else, it would be more fun to write about than contemplating the future decline of Twitter, or X, or whatever we’re supposed to call it at the moment.

For now, Musk might have the best shot at creating something new and worthwhile if he were to focus on adding a few features that are obviously tied to Twitter’s traditional virtues as a tool for quick communications. That wouldn’t turn it into an everything app. But hey, we can use all the several-useful-things apps we can get—and if Musk spent more time creating one and less time tweeting, everyone involved would be better off.

More on Evernote alternatives

In last week’s Plugged In, I wrote about my reluctant abandonment of Evernote and quest to find a note-taking app that feels like it’ll be around for as long as I intend to be. Many of you wrote to tell me about your similar journeys, including truly dedicated Evernote users such as Robert Winter, who has 46,400 notes (!!!) stored in the app. Herewith, some of your recommended Evernote alternatives:

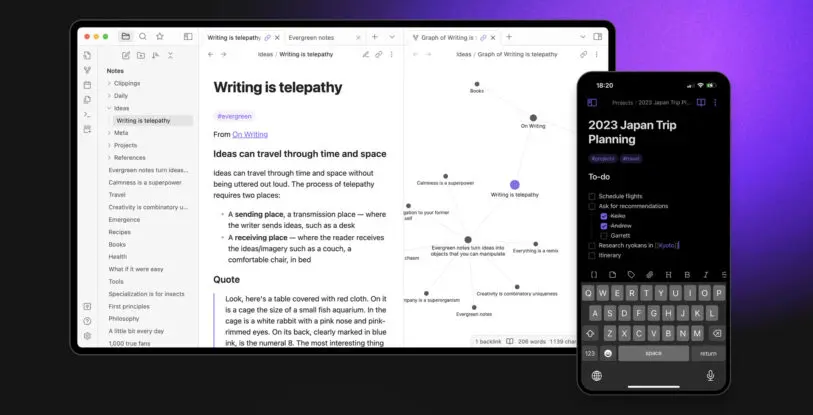

Obsidian. This notetaker—available for every major platform—easily got the most mentions: “It’s robust, has a vibrant community, is flexible, and the data is and always will be all mine,” wrote a correspondent who goes by Ariadne A. The app syncs notes among your devices rather than storing them in its own cloud, and stores them in the open Markdown format—two design decisions that reduce my worries about becoming too dependent on a single app and company.

Apple Notes. Jorge Casales is in the process of moving his 4,000 most-important Evernote notes (out of 19,000 total) into Apple Notes, which he says “has come a long way and supports tags.” I dabble in Apple Notes myself and consider it one of Apple’s sleeper successes: It’s really solid these days. But as much as I like my iPhone, iPad, and Mac, I want to store my own essential jottings in something that also supports Android and Windows.

Microsoft OneNote. My friend Jim Louderback name-checked Lotus Agenda, an ’80s information organizer that still makes some of its onetime users misty. These days, he adds, “OneNote works great so far for me. I would tell you when my earliest note in OneNote was, but oddly the search is still awful.”

Plain old text files. Gary Stringham wrote with a wild-card possibility I’d already been toying with: saving notes as .TXT files and then using a cloud-storage service such as Dropbox to keep them safe. He’s been doing this to wrangle notes of his dating back to January 1, 1987—and just to prove it, he sent me the very first one he wrote:

“This year I am going to write my journal on my computer. I can write faster and neater and I tend to say a lot more when I type than write. Besides, it is a lot easier to erase mistakes written on the screen than mistakes written in pen.”

Thanks for the suggestions, everyone. At the moment, I’m reasonably happy with Notion—but it’s always great to have options.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.