This story is part of an ongoing series about Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’ policies and how they impact the people in his state. For full coverage, click here.

ST. PETERSBURG, FLORIDA — During a Sunday service at Allendale United Methodist Church in St. Petersburg, Florida, last year, about 30 conservative activists showed up to protest on the front lawn.

According to Raegan Miller, who attended the service, they were screaming on megaphones, and some attempted to enter the church. Miller slipped out early with her children for their safety. It was the last time she attended services.

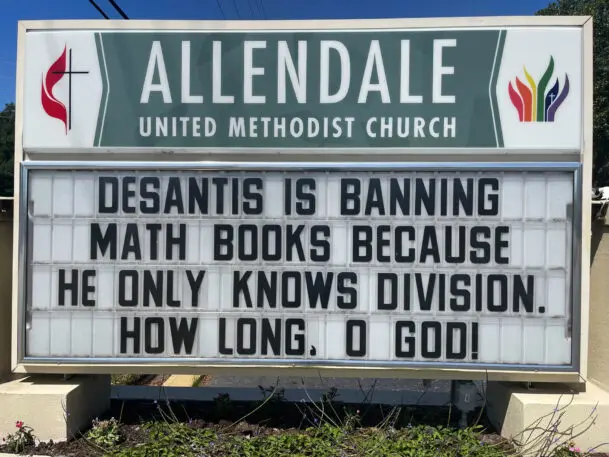

They were protesting a sign outside the church that read: “DeSantis is banning math books because he only knows division.” It was a small act of defiance against Governor Ron DeSantis’ draconian education bills, which have restricted course content to exclude certain race and gender topics, and led to widespread book bans. “It was really scary,” says Andy Oliver, the pastor who put up the sign. But, he adds, “The climate in Florida has necessitated us to be bold in the things we do.”

In picturesque Pinellas County, a peninsula that’s home to the artsy hub of St. Petersburg and the sandy shores of Clearwater, residents are resisting the censorship in small but meaningful ways, including pastors leading banned-movie discussion groups, parents running book drives, and teachers continuing to conduct classes as normal even as they fear losing their jobs.

Parents distributing free books

Two major bills that passed the Florida legislature and were signed into law by DeSantis last year have targeted education as it relates to gender and race. The Parental Rights in Education (or “Don’t Say Gay“) bill, which went into effect last July, banning public schools from teaching about gender identity or sexual orientation from kindergarten through the third grade, was recently expanded to include all grades. The Stop WOKE Act outlaws instruction that could make any student feel uncomfortable, which has largely targeted discussions of systemic racism in the U.S. and its historical origins. These laws have allowed parents to object to any books in the classroom that they deem to be “woke.”

With that backdrop, some residents are helping to circulate targeted books elsewhere. Nicole St. Leger, a mother of four, is a steward of a Little Free Library outside her home in St. Petersburg. These libraries dot neighborhoods across the country: They’re the small public bookcases on sidewalks with the “take a book, share a book” exchange model. For St. Leger and some of her 270 co-stewards in St. Petersburg, (who refer to themselves collectively as a “shush” of librarians), their little bookstalls have provided an opportunity to stock books that foster diversity.

Buying her own books where necessary, St. Leger works to ensure her library is stocked with titles that allow the reader to both reflect on themselves and their place in the world, and to understand someone else’s history or culture—what she calls “mirrors” and “windows.”

“It’s not okay to only have one type of book that is a mirror for one type of person and a window for everyone else,” says St. Leger. She’s concerned that banning certain books will strip away empathy and give students a narrower worldview. At relevant times of the year, St. Leger has carefully curated her library for diversity, putting out books related to Asian-American history, mental health awareness, Pride, and Ramadan.

One of the books she’s featured is Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, a novel about a Black girl growing up in an abusive home during the Great Depression. It was temporarily pulled off school shelves in Pinellas County, due to parental objection of a rape scene over four to five pages of the book. (It was reviewed by the district and placed back on the shelves.)

St. Leger says that Pinellas County, which voted for Biden in 2020 (and Trump in 2016), has handled book assessments better than other counties. The laws are written vaguely, so each county can assess books in the way they see fit. School districts in surrounding counties have brought the hammer down in more aggressive ways, pulling books off shelves at any objection. They’re removed—and often permanently banned—by special committees, which are generally appointed by school boards. In some counties, the school boards are dominated by groups like Moms for Liberty, the prominent “parental rights” group that has driven many of the state’s education changes, and which the Southern Poverty Law Center this week labeled as an “extremist anti-government group.”

Some of the books banned in surrounding counties include The Kite Runner, a novel about an Afghani boy growing up with the backdrop of war; and And Tango Makes Three, a children’s book about two male penguins who adopt a baby penguin. (St. Leger’s husband suggested buying all of Florida’s banned books for their library, but reconsidered after realizing the state has banned more than 350 as of April.)

St. Leger uses Facebook and Instagram to show what’s on display and alert people in surrounding counties that they can access certain books. The drive has inspired other libraries around the U.S. to send donated books to her library, including from stewards of the Little Queer Library in Waltham, Massachusetts, and the Anti-Racist Little Library in Birmingham, Alabama.

A pastor offering a woke solace

Come July 1, Pinellas County won’t be able to remain so lenient. A new law that DeSantis signed in May means any book that any county resident deems “pornographic or sexual in nature” will have to be removed from shelves within five days for review.

Oliver, pastor of the Allendale UMC, finds this hypocritical when there’s a notable exception. “You can’t object to the Bible, which includes rape and incest and polyamory,” he says. “If you’re going to make an argument for a book that should be banned based on their values, the Bible should be definitely at the top of that list.”

He commends the book drives, but says reading alone isn’t the same as doing so with others. “There’s something special that happens when a book is being read together as a class,” says Oliver, who has two sons, in sixth and eighth grades. He grew up in a conservative household, and his worldview was challenged through class reading, but he says he wouldn’t have individually sought out certain books from free libraries.

That has led him to hold banned-book readings during Children’s Time at Allendale, an openly progressive church with a history of activism, dedicated to “the liberation of all people.”

It has also hosted movie screenings, including the 1998 Disney film, Ruby Bridges, based on the true story of a 6-year-old Black girl selected to attend an all-white elementary school in the South in 1960, the early years of school integration. The film was objected to and temporarily removed from shelves at a Pinellas elementary school in March, when two sets of parents said it teaches that “white people hate Black people.”

The church is hosting drag queen preachers every fifth Sunday to lead music at services, and it has made an African-American studies course available online. And, of course, there are the lawn signs, like the one that caused the Sunday morning protest last year. Its signs this month for Pride: “Blessed are the woke” and “God: the original they/them.”

All of this is part of a “resistance to what DeSantis is doing,” Oliver says. Nearby residents have heard about the church and joined, including those who don’t view themselves as religious and others who had vowed not to attend a church again.

Teachers resist—by doing their jobs

The laws have created an environment that makes it difficult for teachers to teach. Under the Stop WOKE Act, parents can sue a school or district if they feel that their children are being made to feel “discomfort” or “guilt,” feelings that are hard to quantify. Teachers have to decipher the vagueness in these laws, which high school history teacher Brandt Robinson says is intentional. “What they’re trying to do is intimidate teachers,” says Robinson, a teacher at Dunedin High School (incidentally, the school DeSantis graduated from).

Sometimes, the resistance comes in the form of teachers simply conducting their classes as normal. Robinson has no plans to alter his lessons or methods. His world history class touches on African history, including the transatlantic slave trade and the Middle Passage. He also teaches African-American studies, which cover the Black experience in America.

Many of his colleagues are instead self-censoring. He says they’re now avoiding anything that could be deemed divisive or controversial. “They’re much more cognizant and aware, and in some cases fearful, about the way that they teach the material,” he says. If they’d previously read first-person slave narratives with the class, or shown emotional video clips, they’re no longer doing that, he says. Administrators at the school that St. Leger’s children attend have taken down “safe space” stickers from classroom walls.

Teachers are concerned about their own livelihoods. A bill signed by former governor Rick Scott in 2011 places new public school teachers on annual contracts, meaning they’re evaluated and have to be rehired at the end of each year based on performance.

But veteran teachers like Robinson are in a rare position to carry on as they had before; Robinson has taught at Dunedin for 26 years, and so is grandfathered into a permanent contract. And he’s happy to take a stand—even after he was targeted by a Moms for Liberty member, who said the curriculum for his African-American Studies class involved critical race theory and Marxist indoctrination, and was “inherently racist.” (The county sided with Robinson.)

He hasn’t changed his methods or course curriculum. And he’s started a TikTok account where he explains facts about issues like critical race theory, and raises provocative questions like, “Is God male or female?” (He knows he’s followed by many Moms for Liberty members.)

In the future, many decisions may not be up to him. The harsher book bill comes into effect July 1, and separately, DeSantis has threatened to ban the AP African-American Studies course in Florida. But for now, Robinson is teaching as he has for decades. “I’m not in any way, shape, or form concerned about it,” he says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.