There’s a cautionary saying within the Black community that’s worth exploring if user experience professionals are committed to being human-centered and inclusive within workplace experiences: “All skinfolk ain’t kinfolk.” At the heart of this saying is something that’s often overlooked when UX leaders advocate for diversity, equity, and inclusion—the complex reality of historically minoritized leaders actively discriminating against their own communities.

The harm that follows is not only the antithesis of being inclusive and human-centered, but it’s often unknowingly perpetuated by white leaders who assume that all historically minoritized leaders are champions of their own community. We see evidence of its harm the most among design leadership, where there is often little accountability or safeguards related to unchecked privilege and bias because of leaders’ proximity to power.

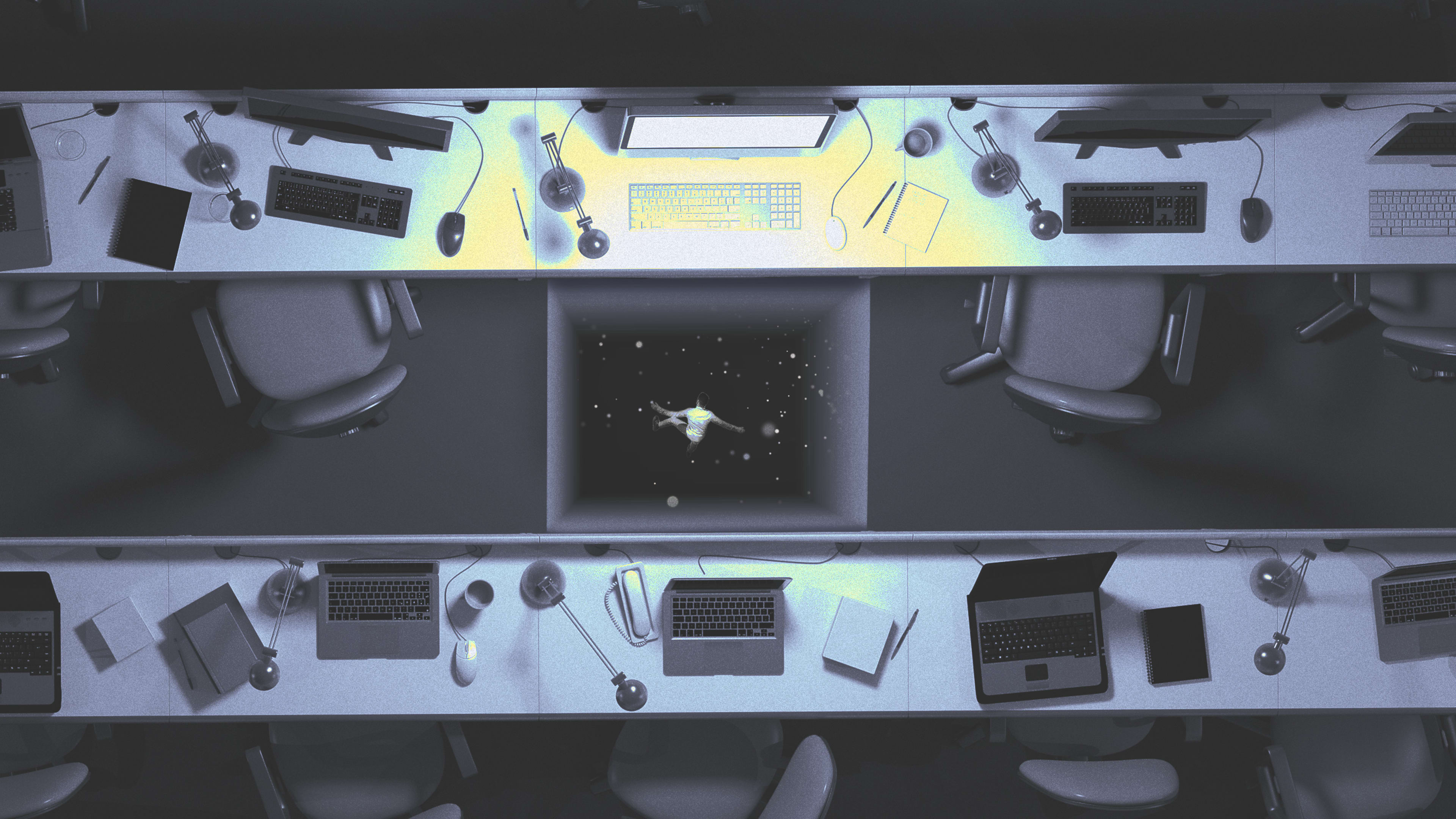

In other words, the “Sunken Place” is real.

There’s a scene in Get Out, the 2017 box-office thriller, in which the audience is introduced to a terrifying reality that the main character, a Black man, finds himself descending into after being hypnotized by his white girlfriend’s mother: it’s called the Sunken Place.

Jordan Peele, the director and writer of Get Out, shares how the Sunken Place is something that exists “for any marginalized group that gets told not to say what they’re experiencing. It’s the system. It’s all these cogs in the wheel that sort of keep us where we are. The Sunken Place is the silencing. It’s the taking away of our expression, of our art.”

Peele speaks to a disturbing, yet common, phenomenon in the UX world: the habitual silencing of historically marginalized voices by those who, in pursuit of their individual career goals, rest comfortably in their lack of understanding or inability to comprehend what it means to be human-centered.

The Sunken Place and Leadership

The structure of an organization—and one’s place within it—determines a person’s access and approach to navigating that structure. A combination of factors such as level and political cachet (i.e., one’s standing in the eyes of others) may grant someone very limited or seemingly unlimited access to choices that impact their livelihood. So when people of color are relegated to the Sunken Place, where they are victimized by the silencing that occurs in white corporate spaces, these factors become critical determinants of the depth of our descent.

The design industry has dire racial and ethnic representation, yet prides itself on being human-centered. What happens when designers of minoritized communities who do make it through the door are socialized and hypnotized into an abyss of powerlessness where they believe their own identity is a liability? What happens to their imagination if they enter the clutches of the approving white gaze?

Bringing the fullness of who we are—bringing our lived experiences to the workplace and our expertise to our work—has resulted in isolation, tokenization, harassment, and career immobility, among other costs. For employees of color, it seems the only available choice is to capitulate to this imposition: Stay under the radar, “play the game” in public, and strategize in private.

But we see a divergence in the way this ethic of survival is practiced among employees in nonmanagerial and executive roles. Between these two groups, who more often plays the game in service of communal benefit or individual gain? Who is more likely to resist or further the silencing?

Despite having also been victimized by the silencing, there are leaders who internalize the Sunken Place and become “voluntary participants” in its maintenance. They take pride in, and assign value to, playing the game. They will mask their identity to become more digestible in the white gaze and leverage their seniority by developing good standing (i.e., proximity to whiteness) with whomever they identify as holding power.

To protect their newly found political power, they often navigate organizational structures at the expense of those who share their condition; they often silence the voices of others to protect their position of power and privilege—even if it means silencing those within their own community. This behavior can show up as a reluctance to challenge the status quo and a preference for designing user experiences that are familiar and comfortable to the majority.

They hope these behaviors will buoy them at the surface of the abyss where they’ll be freed from the conditions of the Sunken Place. But their pursuit is simply greater access to choices.

Their approach to navigating the organizational structure reflects a “more forgivable, understandable, sympathetic version of the Uncle Tom racial trope,” as Alex Rayner describes in The Guardian. Nevertheless, it is a betrayal to everyone captive in the Sunken Place when these leaders weaponize this ethic of survival for individual gain. Afterall, not all skinfolk is kinfolk.

The priorities of effective leaders within any organizational outfit should include things like the empowerment of individuals, promoting their growth and development, and fostering a culture of inclusivity and collaboration. These are the very ethos of the human-centricity that we desire to see reflected both in the practice of UX and in the workplace culture that supports it.

But even these values can be sites of harm, because when they are weaponized, design leaders in the Sunken Place can turn inclusion into a tool of functional exclusion toward others. These constructs of inclusivity and collaboration are haphazard at best and often ignore ubiquitous diversity, equity, and inclusion data (i.e., disparities across race, ethnicity, gender, disability, etc.).

This helps to maintain the status quo of inequity in hiring, retention, and advancement. It also influences how they lead design teams to think about community engagement in human research and whose experiences are being accounted for in the design process. The impact of their leadership on employees under their supervision and on the maturity of the organization is incongruent with the abovementioned values.

To be clear, the existence of minoritized people within a white supremacist system is entirely involuntary; most, if not all, of us are operating from a place of survival. We live in an oppressive society that structurally places limitations on our existence. We work in highly volatile, hyper-capitalistic corporate and corporatized environments that design narrow spaces for diversity, inclusion, and belonging.

While access to healthy choices is usurped in the Sunken Place, the extent to which design leaders participate in the maintenance and perpetuation of these systems is what distinguishes them. But there is no doubt that under a different set of circumstances, those voluntary participants of the Sunken Place would make very different—more inclusive, equitable, and human-centered—choices.

Untethering Ourselves from the Sunken Place

But what if we could break free from operating in survival mode that only proves to sustain, if not deepen, our descent into the abyss of hopelessness? What if we believed we could design ourselves out of the Sunken Place? What if we believed that we had a choice?

Here’s how we can choose to be more human-centered toward others and ourselves.

To those who are causing harm:

- Get clear on what is your enough: It’s easy to forget about the impact of our words, behaviors, and even our silence on the experience of others when we’re hyperfocused on attaining the next promotion, raise, or paycheck in the workplace. However, that goalpost is often moving because many of us aren’t clear on who we are outside of what we can produce. We aren’t clear on what we’re striving for outside of what a scarcity culture demands of us: more. It’s important to understand what’s driving you, what’s enough for you, and how you can be intentionally human-centered in those pursuits.

- Do a power audit: Create a “Power Journal” as a means of auditing the ways power dynamics play out in the workplace. Note the instances this week when you feel and recognize a difference in the power dynamic between you and someone else. Later, reflect on what was felt and your experience.

- Invest in equity-centered and trauma-informed practices from entities and individuals with documented expertise. Well-intentioned leaders need to recognize that the responsibility of protecting workplaces from traumatization should fall on leadership instead of motivated and passionate employees, especially those coming from historically marginalized backgrounds. More important, leadership cannot assume that all historically minoritized leaders or groups want to do this work or are equipped to do it. Organizations should invest in external support and equip their teams with resources.

To those who are harmed:

- Double down on your authentic self. Despite the trendful promise of being able to “bring your whole self to work,” organizations still impose narrow spaces for diversity, inclusion, and belonging. Elizabeth Leiba discusses never looking at one’s identity as a liability as doubling down on their authentic self. Show up in the most honest version of yourself to widen the space around you and others.

- Don’t play the game, learn the game. Develop an attitude of resistance by complicating the terms of “the game.” Do your work to understand HR systems and the resources that are available to you, so you can find creative, restorative solutions when you or others experience harm.

- Divest emotionally and materially from reward and recognition that incentivizes the maintenance of the Sunken Place. We want you to secure the bag! Whether you are an associate designer or design leader, go after that promotion, that performance rating, that company award. But know that it doesn’t determine your value and worth, nor does it undo the systemic inequity or the silencing you and others still experience.

And when all else fails, remember who you are. You are valuable, beautiful and worthy. Access to healthy choices doesn’t have to be restricted to one’s place within an organization. Find strength in your inherent worth, draw upon your lived experience, and reflect on your cultural heritage and history to define what success looks like to you. And in all things, choose courage over comfort.

Vivianne Castillo is the founder and CEO of HmntyCntrd, an award-winning organization that’s committed to transforming the status quo of being human-centered through courses, community, and consulting.

Michael J.A. Davis is an award-winning equity designer and creative director who served as the founding director of Equity by Design at Capital One and is committed to the life, love, and liberation of everyday Black folk and communities made vulnerable by systemic injustice.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.