A sample of a new material at an Auburn University lab looks like ordinary fabric. But it’s designed to solve one specific problem. “We’ve discovered a unique knit: By its geometric structure, it blocks mosquito bites,” says John Beckmann, an assistant professor of entomology and plant pathology at the university.

Beckmann wanted to find a new approach to dealing with mosquitoes, which kill hundreds of thousands of people globally a year—particularly children under the age of five in developing countries—through the spread of diseases like malaria, dengue fever, and West Nile virus. Millions of other people get sick and survive, but might miss days or weeks of work. (And, of course, even when the bites don’t spread disease, they’re incredibly annoying.)

A typical long-sleeve shirt doesn’t actually offer protection. The research team started by testing samples of existing clothing, and found that even tight knits, like compression gear from Under Armour, didn’t block bites. (As in other labs with mosquitoes, the scientists keep the insects alive by sticking their own arms into an enclosure and letting themselves get bitten; for this study, they did the same thing while wearing sleeves made of different fabric.) Woven fabric has even bigger gaps between fibers that the insects can easily bite through.

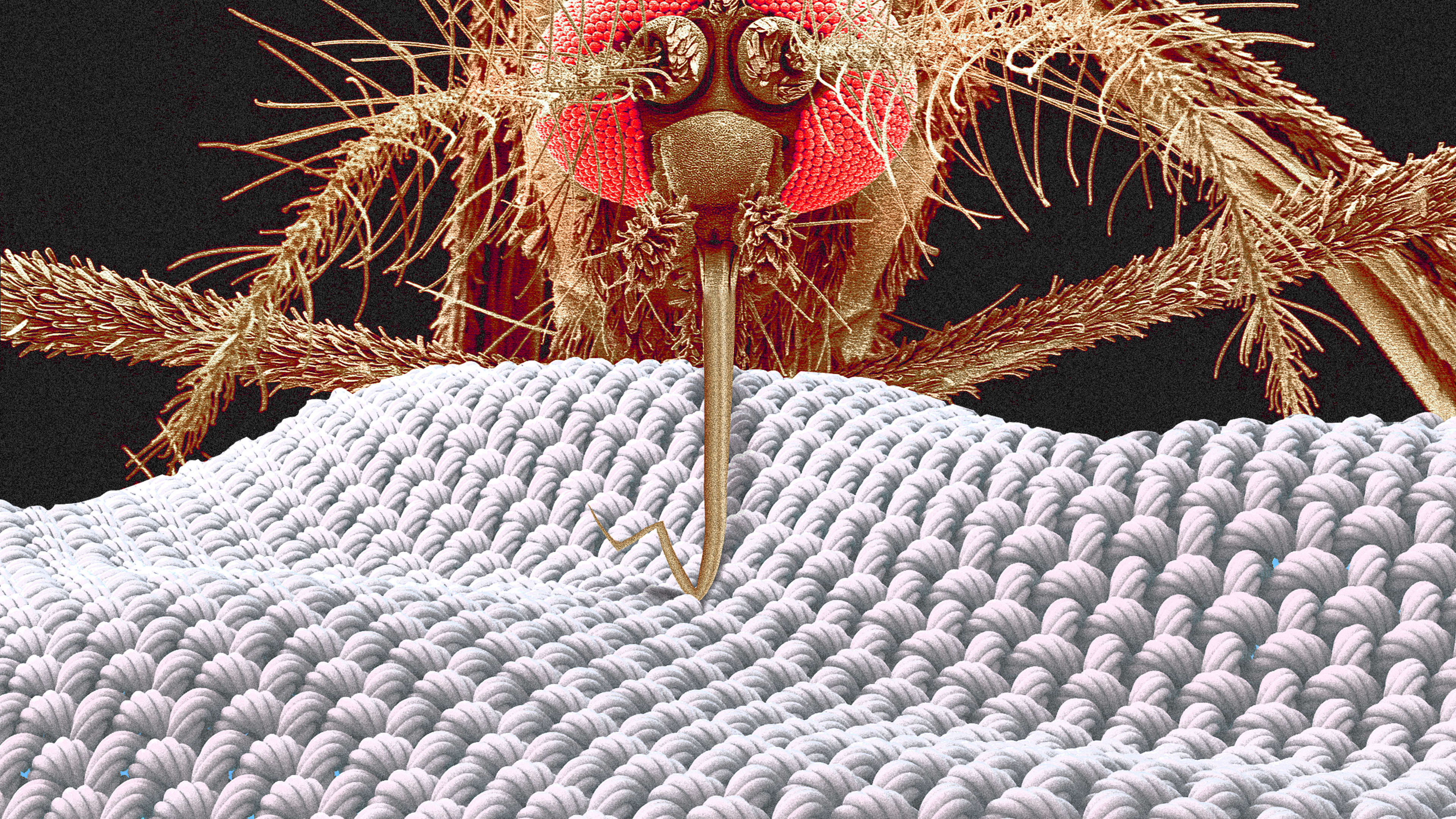

The mosquito’s proboscis, the needle-like appendage that it uses for biting, is longer than most fabric is thick. A preprint paper from the researchers describes the formidable anatomy, including a part called a fascicle, made of “six serrated blades and microneedles” that can bend at 90-degree angles, and adjacent parts called stylets that “saw” skin while vibrating like tiny drills.

Using knitting machines that can be programmed with different patterns, the team experimented until it found a pattern that could block a bite. “Knitting is essentially like tying little knots—you’re making loops, and you’re wrapping loops through loops,” Beckmann says. “If you do it in the right geometric ways, you can create a chainmail effect at the microscopic level.” It’s also carefully designed so that as the fabric stretches and bends, it doesn’t create openings for the insect.

The next challenge was the comfort, since hot clothing doesn’t make sense in the tropical climates where mosquito-borne diseases are the biggest problem. “You want to change the path of the hole just enough so that the mosquito can’t get through, but yet it provides enough airflow that it’s comfortable,” he says. After a lot of tweaking to improve the comfort, some of the graduate students compare it to Lululemon leggings. (While the pattern can be used with various materials, the team is currently working with a blend of Spandex and polyester.)

They plan to continue working on the comfort over the next year, and then spin off a clothing line. Beckmann also hopes that clothing manufacturers begin to license the knitting pattern, which could theoretically be used in almost any garment. In a country where young children often die from malaria, for example, a baby onesie could be made from the knit. The cost of production shouldn’t be substantially higher than typical textile manufacturing.

“If you’re going to compare this to other possible treatments for vector-borne disease, this is going to be a low-cost solution,” he says. Bed nets are also useful, but only when someone is underneath one; governments can also use insecticides to treat communities, but that can only go so far.

Beckmann has also researched techniques for sterilizing or genetically engineering mosquitoes, but that’s a complex process that requires government oversight and massive effort. “More and more, I’ve just been thinking realistically: What do I think can feasibly stop vector-borne disease?” he says. “I think people, and researchers especially, overthink problems and engineer the most complicated solutions possible. I honestly think the simplest solution is probably the best one.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.