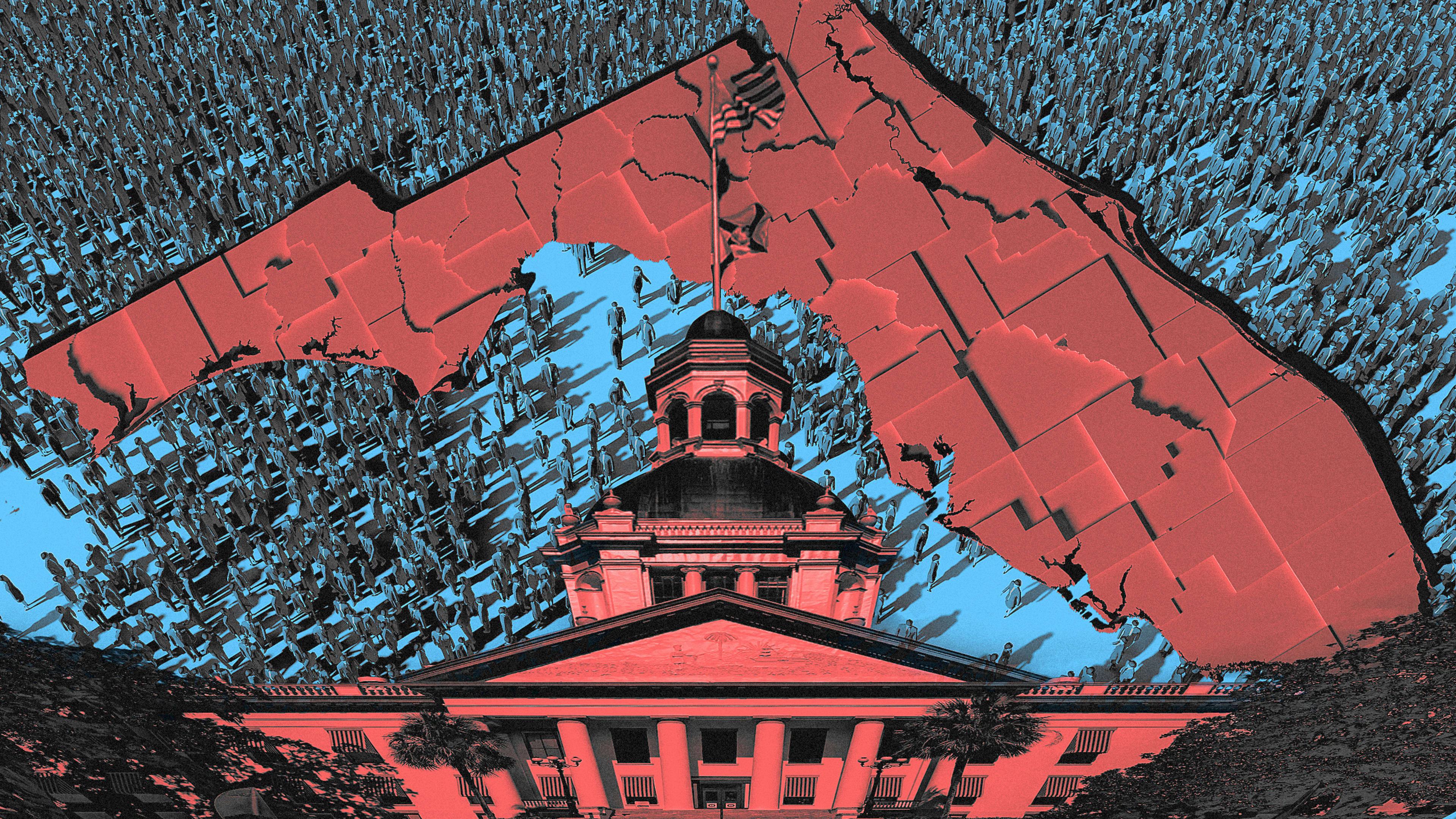

For any member of a union, dues are often automatically deducted from their paychecks. But for teachers and government employees who are union members in Florida, a recently passed bill will add friction to that process, banning automatic deductions from their paychecks and requiring separate payments to their unions.

Labor experts say the law is an attack on the growing labor movement—and just one of a string of recent attempts to make it more difficult for pubic workers to join or maintain their unions.

“My takeaway from this bill is that I’m horrified,” says Sharon Block, a Harvard Law School professor and executive director of the school’s Center for Labor and a Just Economy. “It’s a clear attack on the right to collective bargaining.”

The bill is focused on public sector unions (though law enforcement, correctional officer, and firefighter unions are exempt), but it has broader implications for the overall labor movement—and even our democracy, Block adds. If pubic sector employees can’t easily join unions, or those unions aren’t as effective, “[It’s not] a good recipe for encouraging people to make that decision to go into public service,” she says.

The Florida bill, signed on May 9 by Governor Ron DeSantis, comes after a handful of other bills pushed by Republic lawmakers that roll back payroll deductions for public sector union employees. Kentucky lawmakers passed such a bill in March, while Arkansas passed a bill ending automatic payroll deductions for teachers in April.

And in Tennessee, a bill raising teacher salaries—but with an amendment prohibiting the deduction of union dues from their paychecks—was passed by the state House and Senate this month; it’s currently awaiting the governor’s signature. All of these bills risk weakening unions, which rely on regular dues payments to organize, negotiate, and perform a range of other actions.

The public sector has long had more workers in unions than the private sector. In 2022, the union membership rate among private sector workers was 6%, while the rate of public sector workers was more than five times higher, at 33%. That trend goes back decades; in 2002, the union membership rate in the public sector was 37.5%, compared to 8.5% for private sector workers.

Among specific workforces, the rate can be even higher; across all U.S. public schools, about 70% of teachers are in a union or employees’ association. But that can vary by region, and another provision in the Florida bill takes aim at teacher membership rates, requiring a union to recertify with the state if fewer than 60% of eligible employees are members (previously, the cutoff was 50%). If a union can’t meet that threshold, that union may be decertified as those workers’ bargaining representative. The Florida Education Association has more than 150,000 members, but union rates vary by county; the president of Orange County’s Classroom Teachers’ Association, for example, told Spectrum News his membership rate was around 57%.

DeSantis has defended the bill as a way to give more “freedom” to teachers, and to keep more money in their pockets. But to Cathy Creighton, director of Cornell University’s ILR Buffalo Co-Lab, an extension of Cornell’s School of Industrial Labor Relations, it’s a clear assault on unions, and a way “to weaken his opponents.” Teachers unions have fought against DeSantis on everything from his reelection campaign to COVID-19 mask mandates, and have already sued to challenge the recent law, calling it “retaliation.”

But aside from the tensions between DeSantis and teachers unions, the law is part of a trend aimed at dismantling public sector union membership, labor experts say. “This is part of a campaign launched against labor unions for many decades,” Creighton says. First, it focused on the private sector labor movement, which has seen a rapid decline in union membership; in the 1950s, about one-third of private sector workers were unionized, compared to 6% today.

Both Creighton and Block point to the Supreme Court’s 2018 Janus decision as a turning point in the fight against public sector unions. The Court ruled that public employees didn’t have to pay union fees to cover collective bargaining costs—even if the employees were covered by that bargaining—and it overturned four decades of precedent requiring employees to pay such fees.

“The language in the Janus decision was so hostile to the rights of workers [and] to collective bargaining in the public sector that it is absolutely no surprise that we now see more states . . . taking up that call to try to pass laws that weaken collective bargaining,” Block says. The trend of bills aimed at public unions, she adds, “is part of a concerted campaign to undermine the labor movement overall, and we should all be really concerned about that, because as a historical matter, there has never been a successful, vibrant democracy and a successful, vibrant middle class without a successful and vibrant labor movement.”

After the Janus decision, unions did lose thousands of fee payers, but Block notes that “people who cared about unions came together and worked hard to support and protect their unions.” Ultimately, the aftermath wasn’t as devastating as some experts thought it might be. “I hope that that’s a pattern that prevails in this situation, too,” Block says of the wave of bills aimed at public unions. “But even if that is true, it doesn’t change the fact that it shouldn’t be this hard for people to be represented by a union, and that’s what these bills do.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.