At McSweeney’s, nothing has ever been all that straightforward.

The San Francisco–based publisher once released an issue of its literary journal in the form of a pile of junk mail. It printed another on balloons. It has published books covered in fur, another title with secrets hidden in heat-activated ink, another whose hardcover editions will have an array of seemingly infinite unique covers—and that’s without getting into the profound and/or delightfully absurd stories often contained within the books’ pages. So it should come as no surprise that McSweeney’s latest release is just as astounding.

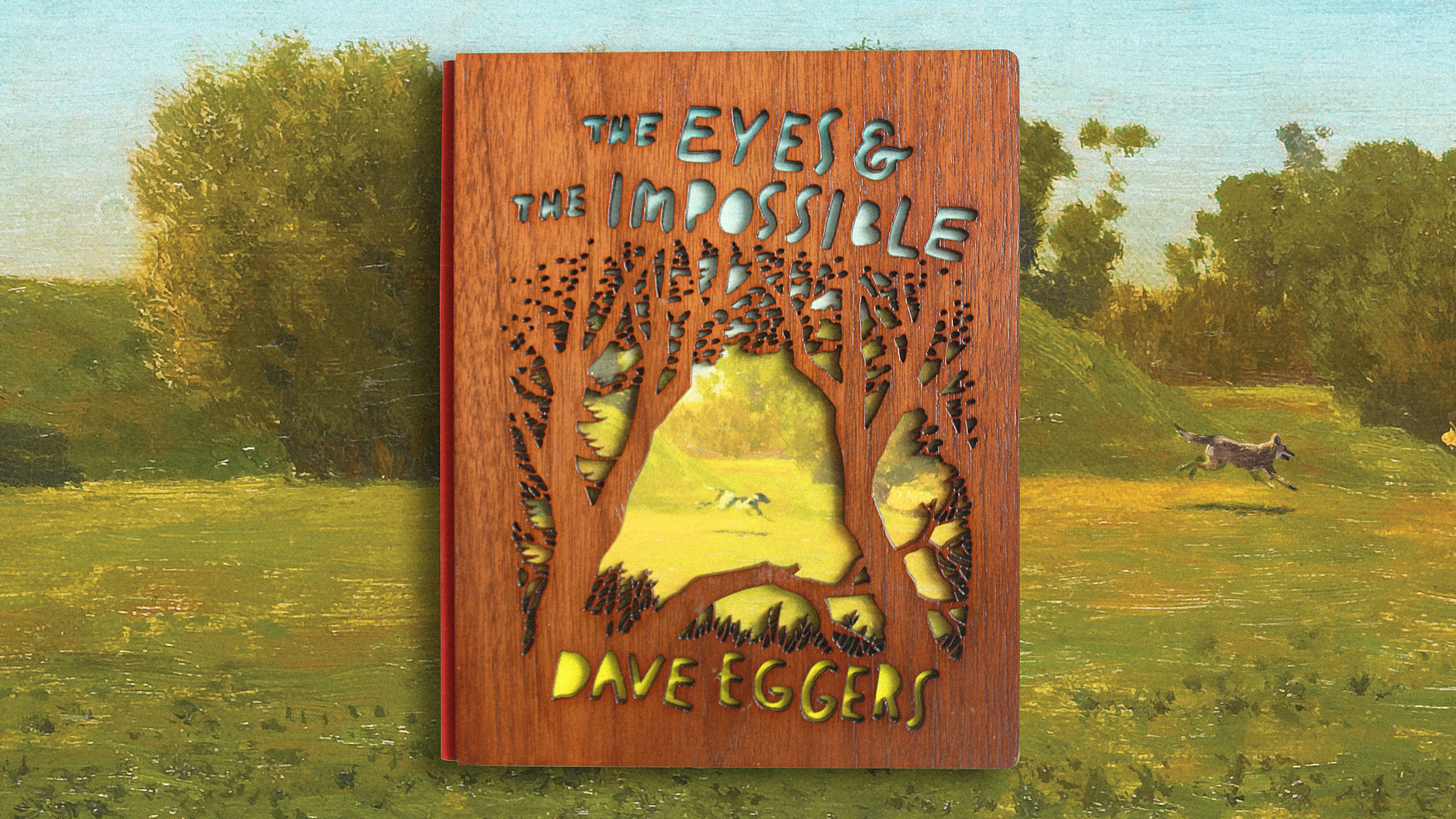

With Dave Eggers’ new book, The Eyes & The Impossible, McSweeney’s (the publishing house founded by Eggers) has a couple of firsts on its hands: the first book to be published, Eggers believes, as a bamboo-wood-bound hardcover; and the first to be published by two different houses (McSweeney’s and Knopf Books for Young Readers) in two different editions for two different audiences (all ages and middle-grade, respectively).

At the “Big Five”—Penguin Random House (parent company to Knopf), Hachette, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, and Macmillan—publishing tends to be a low-margin numbers game, which results in a dearth of creativity when it comes to the form of a book. In the world of children’s publishing especially, categorization is king, with books slotted into tidy tiers making it easier to market to young readers.

But freed from the constraints of needing to turn a huge profit, McSweeny’s has always taken a slightly different approach. In 2014, after a decade-and-a-half in business, McSweeney’s became a nonprofit. One goal of that move, as was detailed at the time: “We want to continue to pursue a wide range of ambitious projects—projects that take risks, that support ideas beyond the mainstream marketplace, and that nurture emerging work.” Today, the company makes around 80% of its revenue from its books and magazines; the rest is from grants and donations—readers who put their financial stamp of approval on its creative experiments.

At McSweeney’s, elements that could seem gimmicky from other publishers tend to enhance a story and the object quality of the storytelling itself. “To keep three-dimensional book publishing alive, you do have to push the form a little bit and delight people and make something new,” Eggers says. “We humans love new things. We love to be surprised. We love beautiful objects. And so why aren’t we always seeking to do that?”

A designer himself, Eggers usually art directs his books. But The Eyes & The Impossible, out today, emerged whole cloth in his mind, something that he says is rare. As he worked on the comical, philosophical adventure of a dog named Johannes who watches over his domain and reports back to a trio of bison elders, he could fully visualize the end product. So, he designed the bulk of it himself.

The text is interrupted at various moments by double-spread, full-bleed classical landscapes, which Eggers’ collaborator Shawn Harris seamlessly painted Johannes into. They don’t bring exact moments of the story to life but rather exist parallel to it.

Eggers wanted a die-cut-wood cover for the book, reflecting Johannes’ environs. Luckily, he was working on the book for his frequent collaborators at Knopf, who Eggers says have long been generous, flexible, and open to unusual arrangements. When the wood-bound cover wouldn’t work for Knopf due to unit costs and other considerations, the publisher suggested McSweeney’s put out a limited edition of the specialty cover, and Knopf would publish the regular hardcover.

“I’ve learned that you do have to trust these ideas sometimes, especially if they’re made early in conceptualizing something, because there’s something in your subconscious or something deep in your gut that’s telling you it’s the right thing,” he says. “Whenever you start compromising, or second-guessing it, then you just end up with the horse by committee. So I’m really more and more unwilling to compromise.”

A shaky P&L has sunk untold numbers of books and ideas, often pushing those unwilling to compromise on things—like creative-production elements—to smaller publishers willing to take the risk and/or accept a lower profit margin. Luckily for book publishing, Eggers founded one.

“We don’t have any accountants at the McSweeney’s offices,” he says. “We don’t have anyone here that will say no.”

Eggers says he wrote the book without a defined readership in mind (just “sentient animals mostly,” he deadpans). He believes publishing for younger readers has gotten to a place of hyper-categorization, and he’s no fan. For Eggers, it goes back to when he was a kid: He recalls looking at books he was excited to read, and then turning them over and discovering they were designated for a younger audience—leaving him crestfallen. For the mainstream hardcover, Knopf did have to declare a readership. But for the McSweeney’s edition, Eggers did not.

“I think it just ends up working out that [the characters] are relatively pure of heart. They don’t have complex Machiavellian tendencies or adult love triangles, and such. And so it ends up being appropriate for all ages.”

In The Eyes & The Impossible, kids will find a fast, thrilling, emotional tale; adults, meanwhile, will discover a rich, layered story that transports them back to the era of literature that informed their future as readers.

One might assume, as this author did, that the design of the two editions would be markedly different to serve a dual readership—but perhaps proving Eggers’ point about the futility of such categorizations, aside from the covers and production flair, the interiors are exactly the same as he designed them.

When it comes to his limited edition, he recognizes that this isn’t the “smartest” way to publish a book. The bamboo cover costs twice as much to produce. Said cover makes it heavier, adding to shipping costs. The production is slower. On shelves, the book costs $28 compared to Knopf’s $18.99 price point. But he has simply always loved multiple editions, dating back to when he was a kid digging up obscure finds at record stores in Chicago.

“It was a really happy departure from mass-market culture to know that there were variations,” he says. “To me, that was the essence of art in the mass-manufactured state, to still retain the freedom to make something unexpected, to make something unusual—to, as a consumer, have that sort of process of discovery, where you don’t really know what you’re gonna get, or you feel like you’re in on some secret, or you feel like you’re seeing something that was made with love and willful eccentricity.”

To some, Eggers’ approach to publishing might feel archaic. Quixotic. Arcane. And, well, it might be.

But when you hold that hefty, impractical wood-bound book in your hand, with its gilded edges and gold foil–stamped spine, you can’t help but feel that he was right all along.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.