American astronauts plan to head back to the Moon in the next few years, closing a 50-year gap in human lunar exploration. The three-and-a-half-year period (from 1969 to 1972) when American astronauts walked on the Moon yielded a huge amount of science that continues to be studied today, yielding new insights. The 12 astronauts who explored the surface of the Moon collected and returned a whopping 842 pounds of lunar rocks and soil, which are carefully controlled by NASA and extremely valuable—so valuable that a group of NASA interns stole $20 million worth of the lunar samples in a 600-pound safe in 2002, but were later busted by the FBI.

When looking at the incredible photos taken from the Apollo missions, you might assume that all the rocks are basically the same gray, dusty material that the astronauts galloped across. But a look through this collection of 1,200 samples from NASA’s Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science (ARES) Division shows that these geologic samples are incredibly diverse and full of surprising features.

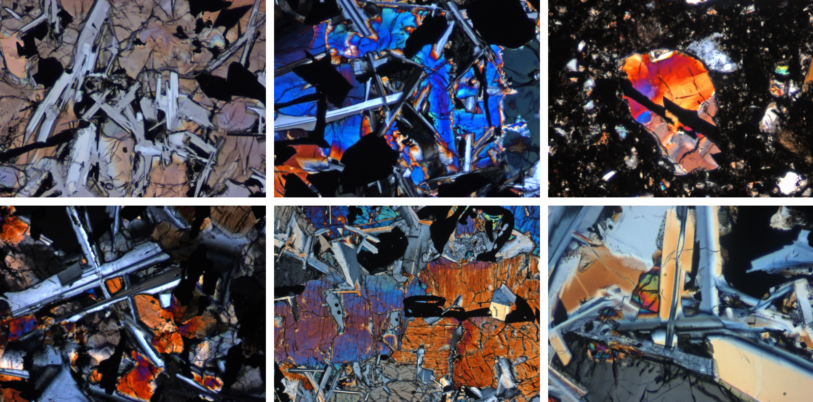

Many samples feature beads or layers of glass resulting from the incredible pressure and temperatures of volcanic forces or meteorite impacts on the lunar surface. Others are riddled with “vesicles,” or impressions, from gas bubbles that were formed in volcanic molten rock. The types of rocks in the lunar sample collection are breccias, basalts, or crustal rocks. Four major minerals are prevalent in the samples: olivine, ilmenite, pyroxene, and plagioclase.

These samples were a major chunk of the work being done by the Apollo astronauts, and it was extremely dangerous work. Without a protective atmosphere, tiny micrometeorites flying like bullets through space could shoot right through a space suit and any time on the surface exposed astronauts to dangerous radiation and cosmic rays. Despite these hazards, 2,196 samples were recorded and collected during 80 hours of work.

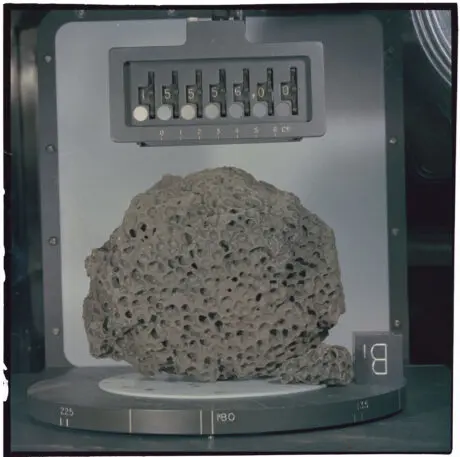

The photos in NASA’s catalog show the rocks on a flat surface, sometimes with color indicators and a manual catalog counter dialed into the ID of the sample. In most of the photos, you can see a small metal cube (1 centimeter square) that in addition to indicating scale also indicates the orientation of the sample with single letter inscriptions for North, South, East, West, and Top and Bottom. A small vertical subscript mark indicates the bottom.

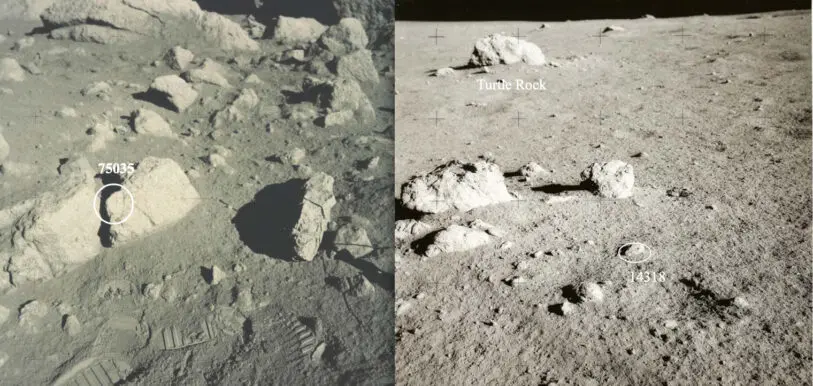

The information recorded about precisely where each sample was found is incredible. Each sample was photographed in place before being collected. This sort of manual data collection must have been extremely difficult in a space suit in such a colorless and uniform environment.

Many of the lunar samples are on public display in museums around the world. NASA’s ARES has a sample loan program for researchers and schools. You can request the loan of a sample for public display here; K-12 schools (in the U.S.) and universities can request “thin section” samples for research purposes.

If you need to get up close but don’t want to go through the trouble of asking NASA for access, you can examine a selection of these samples virtually in exquisite detail in your web browser.

In 2013, artist Erika Blumenfeld approached NASA with the great idea of using the latest imaging technology to create high-resolution 3D scans of the lunar rocks in its collection so that more people around the world could examine them in detail. NASA was interested and soon funded the effort, called Astromaterials 3D. The “Explorer” interface for this project is executed beautifully, allowing you to rotate and zoom in on the 3D model of each sample (which can be downloaded in high or low resolution). Each sample is accompanied by a narrative with interesting details about its collection as well as its dimensions and physical properties.

The coolest part is that NASA has also performed CT scans on these samples, revealing their interior makeup, in thousands of slices, which you can see along any axis. The resulting effect is like taking these priceless samples and cleaving them open with an infinitely sharp blade to see what’s inside. You can even turn on an “analglyph 3D mode,” which with the aid of those red-and-blue paper glasses, gives you a nice 3D view of the sample.

This is truly one the best interfaces for beautiful public data that I have come across.

Republished with permission from Beautiful Public Data, a newsletter by Jon Keegan that curates visually interesting data sets collected by local, state, and federal government agencies.

To see more of the tools used to explore this data, read more at Beautiful Public Data. You can subscribe to the newsletter here.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.