Inside bioreactors in its new lab in London, the startup Modern Synthesis uses sugar from plant waste along with microbes to grow “microbial textiles,” which could eventually help replace both leather and synthetic fabric made from fossil fuels.

“What we’re trying to build is a new bioeconomy that’s built around more efficient systems that convert waste—in our case, waste sugars from agricultural production or other sources—into high-quality materials that can then be circled back,” says cofounder Jen Keane. “Biology is the ultimate circular economy.” Later, the materials can be recycled, or, depending on how they’re made, composted.

Keane previously worked on material design at Adidas, where she helped the shoe giant make sneakers from plastic waste found in the ocean. But the work helped her realize how dependent the industry was on synthetic materials in the first place. “Even though we were recycling these plastics, which is an important first step, it wasn’t the end solution,” she says. “I wanted to look at, Okay, how can we fundamentally rethink the way that we approach materials?”

She joined a master’s program in biodesign and started meeting with synthetic biology researchers at Imperial College London who were studying a bacteria found in kombucha, called K. rhaeticus, which produces a material called nanocellulose.

“Cellulose is the building block of the natural world—it’s in cotton, wood, linen, a lot of the materials that we have today,” she says. “But these bacteria produce it at such a small scale that the fibers are very strong, and they bind to each other really naturally.” The fibers are stronger than Kevlar, and the tensile strength (or how much stress something can withstand before being pulled apart) is higher than that of steel. While nanocellulose is already used in some products, including face masks and bandages to help heal wounds, Keane was interested in how it could potentially be used in the apparel industry.

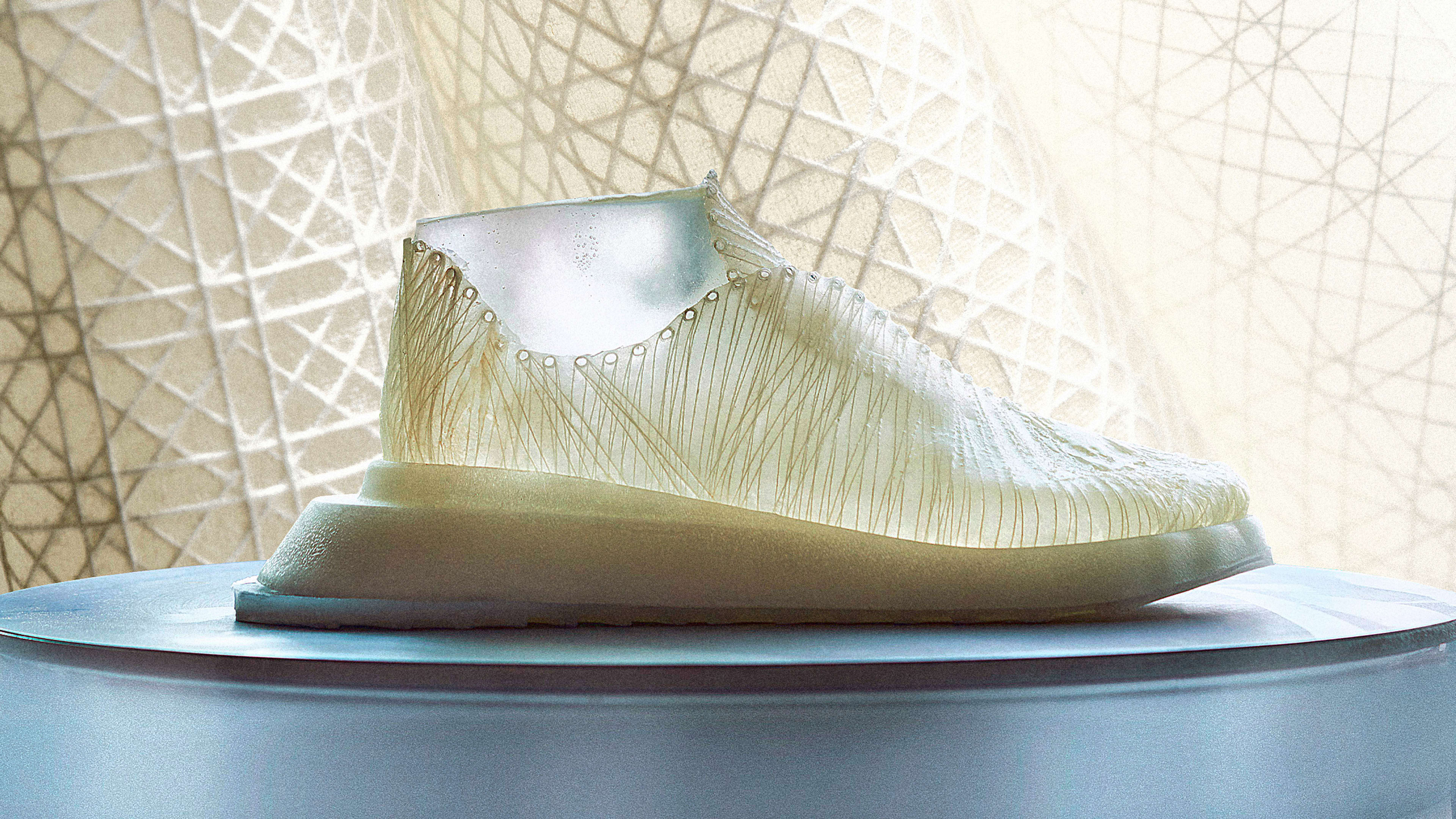

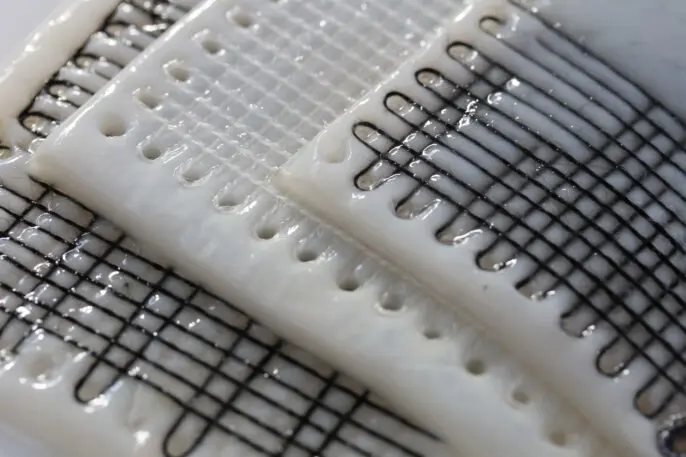

Working with cofounder Ben Reeve, a scientist from Imperial College, Keane developed a new system to create textiles with the microbe. The process starts by using a robot to build other natural fibers into a scaffold for the microbes to grow on. As the microbes feed on sugar, they “weave” the new textile around the shape of the scaffold, forming a hybrid that includes both the original scaffold material and the nanocellulose made by the microbes. (The microbes themselves don’t end up in the final product.) “You can use textile structures that wouldn’t be structurally sound otherwise,” Keane says. “We can create these almost net-like structures that would be quite flimsy or just fall apart on their own. They’re actually strengthened by the biomaterial.”

It’s also possible to grow a final product—Keane’s first prototype as a student was a shoe formed by the microbes. But she says that the company plans to begin by making a material that clothing brands can cut and sew, so it can scale up more easily.

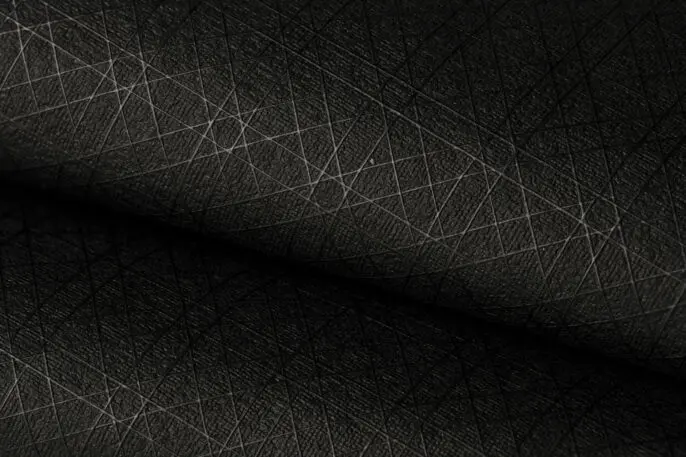

The first samples of the material produced at the company’s pilot facility look different than any existing materials. “It’s naturally transparent, and it almost looks like a nylon or a really technical synthetic fabric,” Keane says. “But the feel is much more natural. And it’s adaptable in terms of its hand feel.” It can be more flexible, for example, or thicker. It also can be designed for more durability, though that means the material wouldn’t naturally biodegrade as easily.

If it replaces synthetic fabrics, it can help avoid the environmental footprint of using petrochemicals. By one estimate, around 350 million barrels of crude oil a year are used to make synthetic textiles. If it’s tweaked to look and feel like leather, it could help avoid the environmental and ethical problems involved in raising livestock. (Bucha Bio, another startup, is using similar techniques to make leather alternatives.)

Since moving into the new lab a month ago, Modern Synthesis is focused on making samples that demonstrate how the material could be used. It currently makes full sheets of the material for brands to use in prototypes, although more R&D is needed to meet its stringent materials standards, Keane says. Over the next few years, it plans to move to full-scale production.

The company is using a mix of off-the-shelf equipment to try to make it easier to grow. “Our first priority is, how can we retrofit what exists to build the capacity that’s out there in the market for these materials,” Keane says. The biggest question for the startup, and others in the space, is “How fast can you scale?'” she says, “because the demand is there.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.