Baseball’s slow era may be over.

In recent years, the duration of the average nine-inning baseball game has stretched the patience of both fans and players. Games could drag on for more than three hours, when most fans prefer something closer to two and a half.

The games had gotten so much longer because the play had gotten slower—pitchers and batters taking long pauses between each pitch, for instance—and during the slow games, there was less exciting action to watch. The culprit, many believe, was the infield shift.

The shift has been a widely used strategy in recent years and involves changing where infield players stand to match the hitting patterns of batters, forming a lopsided defensive wall in the space a hitter is most likely to send a line drive. Stuffed up, many batters responded by trying to hit over the shift and over the fences for a home run. Many succeeded. Most struck out.

“All this conspired to create the constipated baseball of 2022 and recent years,” says Gary Gillette, a baseball historian and author of several books on baseball stats and stadia. “You have many fewer balls in play, very low batting averages, very little base path derring-do, and a whole lot of balls hit into the stands.”

So, Major League Baseball set out to de-constipate the game. A league-level Competition Committee made up of team representatives, active players, and umpires, began meeting last summer to weigh potential changes to the game, including adjusting the strike zone, moving the pitcher’s mound, or even redesigning the baseball itself. In the fall they approved three significant changes for the 2023 season: increasing the size of the bases, enforcing time limitations between game elements like pitches and pitcher changes, and eliminating the infield shift.

“These steps are designed to improve pace of play, increase action, and reduce injuries, all of which are goals that have overwhelming support among our fans,” MLB commissioner Robert D. Manfred, Jr. said at the time.

Yes, the rule changes are undoubtedly aimed at improving the pacing and reducing the duration of games. But they’re also part of the business strategy of a professional sport whose most avid fans tend to be over the age of 55, and which saw ticket sales decline every year from 2012 to 2019. Purists may object (and they have, strongly), but long, slow games represent the main symptoms of decline for America’s pastime.

Despite any opposition to this season’s changes, redesigning the flow and excitement of the game is part of a long history of baseball’s rulebook being adapted to respond to the way the game is actually played. Through that history, the game has been significantly altered by physical changes to the field and how players use it, and that’s especially true this year, which may be the most altered season of baseball in the last century.

“This is kind of an unusual year to have so many changes all at once that actually impact how the game’s played,” says baseball historian Kevin Johnson, co-chair of the ballparks research committee of the Society for American Baseball Research. “They’re not just cosmetic changes.”

Baseball’s rich tradition of changing its own rules

From the strike zone to the location of players to the height of the mound to the playing field itself, many of the changing shapes of baseball date back to the game’s earliest days and the amorphous way it took physical form.

In the early 1800s, the first ballparks were actually parks, or at least wide open spaces. They had the essential geometry of four bases and a pitcher’s mound in between, but the rest of the ballpark was mostly undefined. The outfield was often an actual field spreading out into the distance or onto the nearest farm, and there were no walls. “People would just walk onto the field, or walk across with their cow,” says Johnson. “So, they started putting some fences up.”

Once there started to be dedicated places for baseball as a spectator sport in the late 1800s and early 1900s, fences became part of the way teams could charge for admission. And as the sport grew in popularity, the V-shaped grandstands centering around home plate were insufficient. Savvy ballpark owners spread seating around the full perimeter of the field, often pushing the outfield walls inward to make room for what became known as the bleacher seats. “At that point, hitters started hitting the ball over the fence, not just to the fence,” says Johnson. “So, the fence actually became more important.”

But into the so-called modern era of baseball beginning in the early 20th century, the fence was never standardized. Due to the early urban nature of professional baseball, ballparks were built on valuable real estate and often surrounded by the density of cities like Boston and New York. “You had to fit a ballpark into the piece of land, and that’s where you got ballparks that were basically different in every single city,” says Johnson.

As a matter of real estate, every baseball stadium is essentially its own specific field of play, and each team’s organization is granted a reasonable amount of flexibility in deciding the dimensions of that field. And almost every season, one or two teams change those dimensions. For the 2023 season, the Detroit Tigers decided to modify the height and distance of its outfield wall, bringing center field 10 feet closer to home base, and cutting between one and a half and six feet off the height of the wall from center field to right field.

“The outfield wall changes, combined with new rules from Major League Baseball in place this season, have the potential to create even more excitement and on-field action for years to come,” said Detroit Tigers president of baseball operations Scott Harris when the changes were announced in January.

Changes to the field’s dimensions are often framed as efforts to improve the game, but they are also shrewd business decisions. Outfield walls have been moved to create more seating for fans, a clear boost to a club’s revenue. They’ve also been moved to enable more or fewer home runs, game-affecting efforts that may be more significant as tools for recruiting stat-conscious players to home stadiums that are pitcher- or batter-friendly. For teams, “it’s a consideration,” Johnson says. “They’re thinking ‘if our ballpark is not good for pitchers, then pitchers may not come play for us.’”

Like those moving walls, the rule changes instituted in the 2023 season are as much about the game as they are about the business behind the game.

2023’s smallest tweak brings big excitement

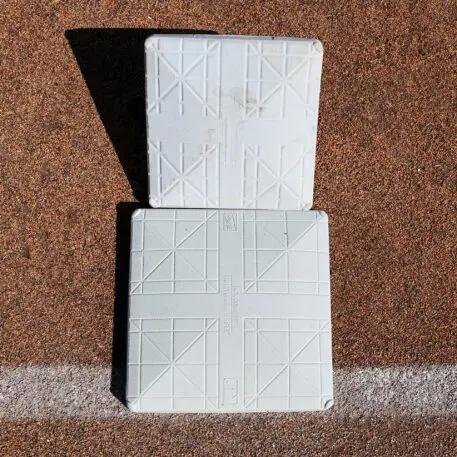

The most historic change of 2023 may be the smallest. For the first time in over a century, the size of the bases is growing, from 15 inches square to 18 inches square. “Bases haven’t changed for over 150 years. The base is kind of a big deal,” says Johnson.

This additional 99 square inches of area decreases the distance between bases by 4.5 inches. That may not sound like much, but it’s less space a runner has to cover, giving less time to defensive players to throw or tag runners out—game-deciding plays that are often measured in inches. In tests at the minor league levels, the bigger bases were correlated with fewer crash injuries between runners and base tenders. The bigger bases, importantly, are also intended to incentivize base stealing, one of the riskier and more exciting parts of the game.

So far this season, the plan is working. The league’s first day of play saw the most stolen bases for an opening day since 1907. “There’s been a very noticeable change,” says Johnson. “Stolen-base success is way up.”

Gillette says a new game pace-related rule limiting the amount of time-burning pickoff attempts—trying to throw out a runner leading off from a base—has also played into the increase in stolen bases. Even so, the bigger bases have been welcomed. A source familiar with the negotiations between the union and the league said larger bases have been under consideration for seven or eight years. When the league’s official Competition Committee eventually voted on the proposal last September, it passed unanimously.

Other changes reshaping the game in 2023 have been more controversial. Pace-of-game rules, particularly the timer that limits how much time a pitcher can take between pitches, have rankled some players, as have limitations on the infield shift. The players union, which holds only 4 of the 11 voting seats on the MLB Competition Committee deciding rule changes (and thus cannot unilaterally block any new rules), voted against both of these changes for rushing pitchers and batters. In a statement, the players union said the league was “unwilling to meaningfully address the areas of concern that players raised.” The changes, were tested extensively in the minor league first, were approved by a majority vote.

“Some of these changes are going to stick for a long time,” says Gillette. The pitch clock is probably one, he says. But others will likely face their own redesign some time down the line. Gillette expects the limitation on pickoff attempts to be one change that doesn’t last.

The point of the rule is to cut down the game time spent on pitchers trying, sometimes repeatedly, to catch runners leading too far off first base. The new pace-of-game rule, which limits pitchers to two “disengagements” from the mound, will put an end to that cat-and-mouse game, but Gillette says it will just let runners lead off even farther afterward, leading to more successfully stolen bases. “The problem is every time you change a rule, there are unintended consequences,” he says.

It’s happened before, in substantial ways. Gillette points to what historians know as the crisis of the early 1960s. Between 1961 and 1962, four teams were added to Major League Baseball, and, for a variety of reasons, offense boomed. Roger Maris of the New York Yankees set a home run record that lasted nearly 40 years, and others nearly matched him.

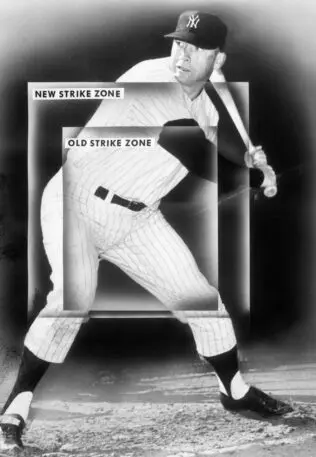

Defensive players, and pitchers particularly, were not pleased. “Everyone said ‘oh my god, we’ve got to do something about this, even though fans like higher offense in general,” says Gillette. “They enlarged the strike zone. They enlarged it so much that basically portions of the strike zone were completely unhittable.” By the late 1960s, more than 20% of games ended in shutouts and scoring was at its lowest point in 50 years. “And the game was boring,” Gillette says. “So, what did they do? They changed the strike zone back to the interpretation it was in 1962 and they changed the height of the mound.”

The rules of baseball, history proves, will change again and again, often as a result of rule changes that came before. Teams and players will find ways to use those rules to their advantage, or to the disadvantage of their opponents, and wins and losses will be blamed upon those tactics. If the league is right this year, the rules it has put in place will help solve the problem of the low action and slow-going baseball of recent years. If not, it will almost certainly try something else.

Ultimately, there are no rules against tweaking the rules of the game, which, after all, is a game. The shape of baseball will remain undefined and amorphous, but always fluid. “I think the evolution is never ending,” says Gillette.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.