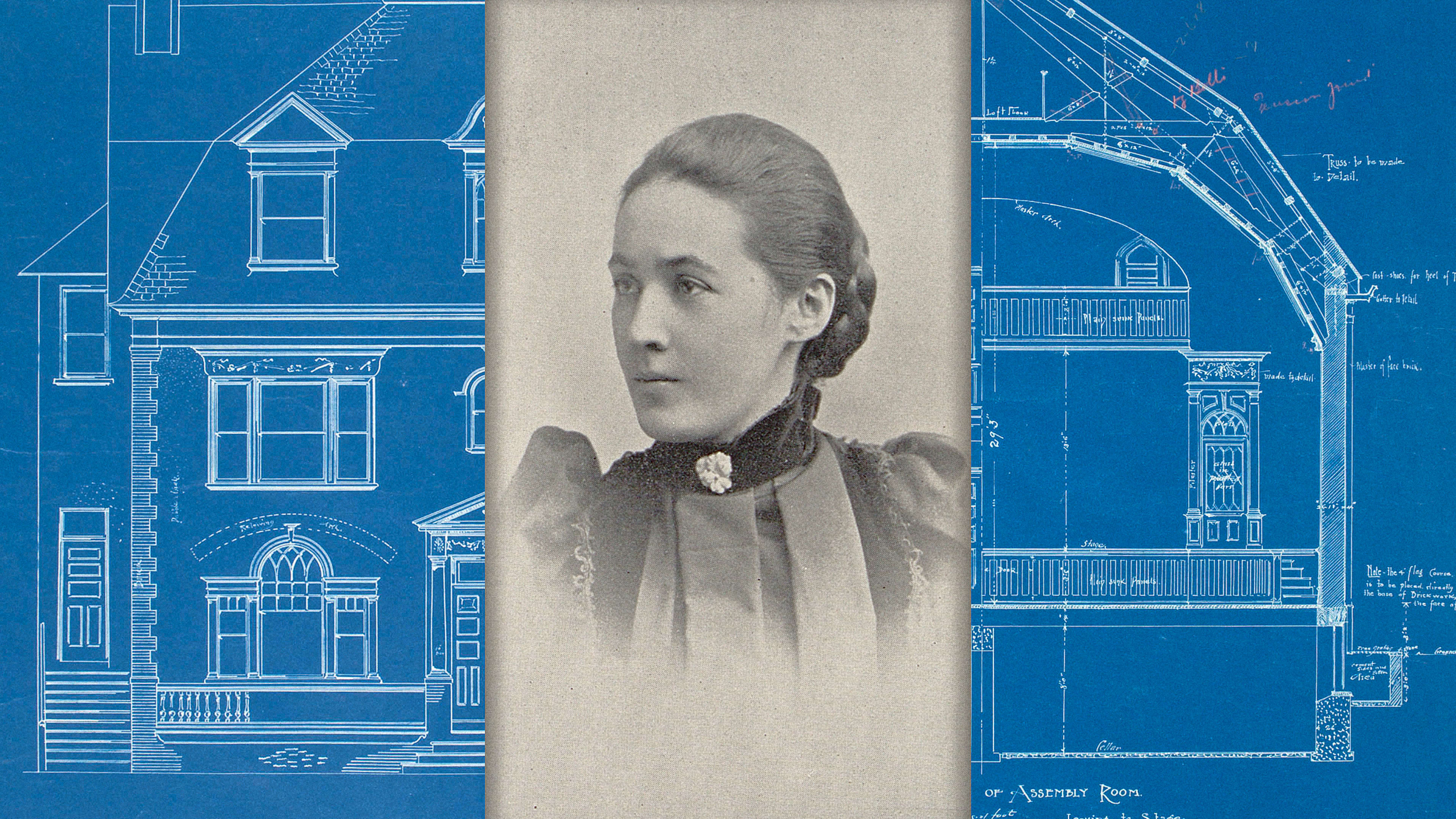

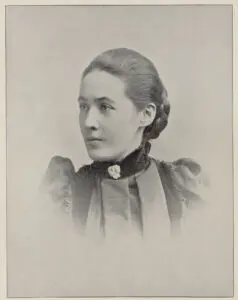

The story of Minerva Parker Nichols is finally being told. A trailblazing architect, she was the first woman in the U.S. to practice architecture independently, designing notable buildings along the East Coast beginning in the 1880s. But while other female architects from the early and mid-20th century have been lauded for their contributions to the built environment, Nichols, arguably the first independent female architect in the nation, has mostly faded from public memory.

Not anymore. The Architectural Archives at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design has just opened Minerva Parker Nichols: The Search for a Forgotten Architect, an exhibition on a life and career that was almost left out of the history books.

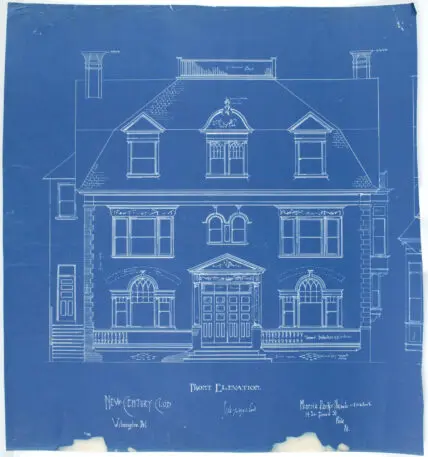

Independently designing beginning in 1886 and opening her own firm in 1889, Nichols conceived residences and buildings including women’s clubs in Wilmington, Delaware, and Philadelphia, as well as an unbuilt pavilion for the famed 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Despite working into her late 80s designing homes for veterans of World War II, Nichols’s contributions have nearly disappeared over the past 70 years.

The research behind the exhibition has been spearheaded by Molly Lester, now associate director of the Urban Heritage Project at the University of Pennsylvania. Based on more than a decade of fact-finding that involved combining scant archival material, family history, and firsthand documentation of Nichols’s remaining buildings, the exhibition fills in the blanks of a pioneering architect’s life.

Nichols garnered some acclaim upon opening her firm in Philadelphia in 1889, and was later featured in a front page article in the Philadelphia Real Estate Record. Several of her buildings received press coverage, including the all-women New Century Club of Philadelphia, which she designed starting in 1891 (and which has since been demolished).

William Whitaker, curator and collections manager of the Architectural Archives at Penn’s school of design, worked on curating the exhibition with Lester. He says Nichols jump-started a slow but steady trend of women entering the architectural profession.

“In the period that Minerva’s entering practice, there are only 17 women who are recognized as working in an architect’s office in the entire country,” Whitaker says. “And that’s out of 4,000 people who identify as being architects.”

But hers appeared to be a short-lived career.

“Once she got married in 1891 her work slows down. She starts having children and she leaves Philadelphia, and the historical record kind of disappears,” Whitaker says. “It wasn’t clear what else she had done. We all just assumed she worked for 10 or 12 years and that was it.”

Lester first encountered Nichols’s story in 2011 while pursuing a master’s degree in historic preservation at Penn. She’d already completed an undergrad program in architectural history but had never heard of Nichols.

“Four years of coursework there and two years in graduate school, I’d encountered very few women in my classes until you get to the 20th-century histories, at best,” Lester says. “So she stood out as this example of a woman practicing much earlier than I gave women credit for in the profession, and much earlier than a lot of people give credit to women.”

Nichols became the subject of Lester’s thesis project, which planted a seed in the mind of Whitaker, who’d known of Nichols from the university’s archives, where a few of her construction drawings from the 1890s were on display. “For years we used that as a simple description for student tours about what architects do,” Whitaker says, noting he had no idea that the woman behind the drawings was the nation’s first independently practicing architect.

Lester and Whitaker set out to turn the research into an exhibition. But there was very little material to work with. They partnered with architectural photographer Elizabeth Felicella to create something close to a comprehensive record of Nichols’s remaining buildings.

“We said, we’re going to create an archive in the absence of one, and we’re going to do that by using photography as a means of not only documenting the work but getting our minds around what she did, how she did it, and the arc of her life and career,” Whitaker explains.

Lester’s research found that while Nichols did close her firm in Philadelphia, she continued to design buildings after moving with her minister husband and children to Brooklyn. Lester has uncovered more than 80 projects designed by Nichols, including schools, social spaces for women and suffragists, and many private residences. About 30 of these projects have been documented and photographed, and these records are now on display in the exhibition. Lester says there are likely even more Nichols projects out in the world that are at risk of being forever unattributed to her.

The project shows the danger of historical blind spots, and the potential for entire historical foundations to be completely forgotten. Lester says the problem is self-reinforcing, as architectural history books tend to cite each other and feature the works already known to be significant. “If it hasn’t been validated by mainstream architectural histories, then there’s a cyclical sense of ‘well, I guess she’s been left out for a reason,'” Lester says.

Nichols was far from obscure in her own time. Her death in 1949 at age 87 warranted an obituary in The New York Times, recognition not bestowed to the more widely known early-20th-century American architect Julia Morgan upon her death in 1957 at age 85.

By the end of Nichols’s life, 1,000 women were counted as working in the field of architecture in the U.S., according to Whitaker. Lester says Nichols’s impact as the first woman to launch an independent architecture practice helped blaze that trail. She’s hoping to find more of Nichols’ works and expand a growing archive that could have easily faded into oblivion. She’d like to help broaden other historians’ views about which histories need to be told.

“I’ve always been interested in how women have shaped the built environment,” Lester says, “whether they’ve gotten credit for it or not.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.