When we talk about the history of Black wealth creation in America, it’s almost always a sad story—one that frequently involves violence, dispossession, and disenfranchisement.

That narrative is of course valid. In the wake of slavery, the Civil War, and Jim Crow, Black Americans were routinely prevented from accessing the resources we needed to develop and pass on wealth.

By “wealth,” I mean much more than just cash. Wealth is the sum total of an individual’s economic access, opportunities, resources, and assets. A healthy bank account is no doubt an important element, but so are housing, education, healthcare, community services, and any number of resources that help ensure financial success and personal fulfillment.

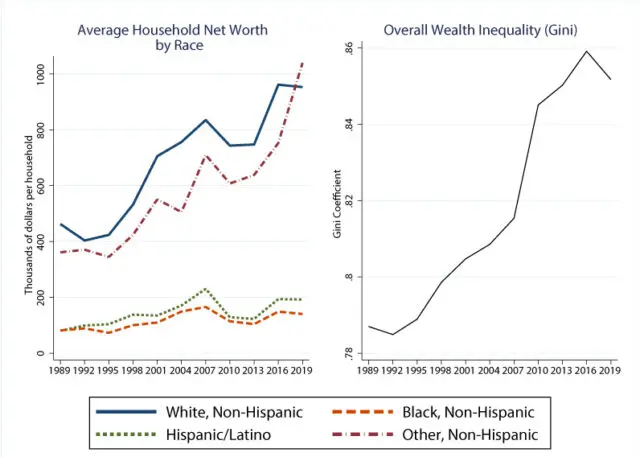

The political and economic disenfranchisement of Black Americans has demonstrably crippled our community’s ability to grow and acquire wealth over time. The income and wealth gaps between America’s Black and white populations persist to this day. Unequal health and education outcomes are still all too common between racial groups.

But at the same time, this is only one, macroeconomic story. It runs roughshod over a much more dynamic and diverse historical record. There was unconscionable violence and dispossession, but there was also initiative, ingenuity, and individual determination. Generations of Black citizens didn’t wait around for their government to hand them opportunities. They scraped and hustled to make their own.

As an entrepreneur, I’ve been reflecting on the history of Black wealth creation and its impact on us today. The world has undoubtedly changed: The opportunities for acquiring and maintaining wealth have grown with each passing year.

But at the same time, it can be hard to maintain an optimistic attitude when Black founders pulled in less than 1% of the venture capital allocated last year. How can we celebrate all the progress we’ve made when the statistics show that Black wealth suffers so many structural disadvantages?

In honor of Black History Month, I wanted to share two stories of Black wealth that occurred against even tougher odds. They keep me going when I stare dumbfoundedly at these statistics and wonder where we’re going and how far we’ve come.

Two figures stand out in this alternative narrative: Mary Ellen Pleasant and Madam C.J. Walker. They were two very different women from very different times. But they share a common trait: Both used their shrewd business minds to amass personal fortunes and support the causes of Black liberation and economic mobility, long before equal legal protections and equitable working practices were extended to them. Their stories are a humbling reminder—especially in the current age of deepening inequality—that acquiring wealth isn’t just about self-interest. It’s about creating more opportunities for all.

Mary Ellen Pleasant: The queen of the California gold rush

Mary Ellen Pleasant (1815–1904) was a Black entrepreneur and Abolitionist who championed the equivalence of personal enrichment and community advancement.

Around 1850, she left to seek her fortunes in the newly formed state of California. Pleasant planned to work as a cook and domestic there, because there was a dire shortage of women heading west. When she arrived, with a considerable net worth from her first marriage already in tow, there was a bidding war among prominent citizens to hire her as a cook in their homes.

Mary Ellen knew from her childhood spent in service work that access to certain households came with perks: most important—in a new state rife with economic speculation—information. While she was working in various white households, she simultaneously soaked them dry for every bit of insider knowledge they let drop.

Over time, she became a millionaire, having invested early in California’s new economy. Railroads, oil companies, restaurants, and even the first Wells Fargo bank all featured in Pleasant’s portfolio.

Throughout it all, she was a consistent supporter of Abolitionism, slave rebellions, emancipation, and desegregation. She was one of a number of Black entrepreneurs who diverted significant funds toward supporting freedom fighters.

But as a woman of color, Pleasant was limited in her avenues to economic independence. It was often difficult to make investments in her own name, and she eventually devised various workarounds. For example, while she could publicly insist that she was merely a cook or servant, she simultaneously worked with her white employers to facilitate her (and their) investments. That’s how influential her opinion was.

In later years, she entered into a highly lucrative partnership with a man named Thomas Bell, and the two amassed millions of (19th century) dollars in the 1870s and 1880s.

With this growing fortune, Pleasant built herself a handsome, 30-room mansion in San Francisco and became a local celebrity. Eventually, after Bell died, his wife sued for control of his estate. Many of the investments Pleasant had made with Bell were in his name, and when the judge ruled in his wife’s favor, Pleasant’s wealth was diminished—though not extinguished.

Mary Ellen Pleasant is a perfect example of how some Black people were able to overcome the political, economic, and generally racist disadvantages that hampered their wealth creation. She was an exceptional businesswoman who used her natural ability to connect with people to invest in California’s booming economy and broker deals for others. W.E.B. Du Bois would later write she was “one of the shrewdest business minds in the State.”

By the time of her death in 1904, the U.S. was busy trying to grow out of the era of slavery and the universal disenfranchisement of Black communities. Pleasant lived cleverly and somewhat covertly, inventing many stories to help explain her money. In the new century, however, Black wealth would emerge into a more public view, pushing some to the heights of luxury while punishing many more with anti-Black retaliation.

Madam C.J. Walker: The first self-made Black millionairess

Madam Walker is frequently touted as the first self-made Black millionairess in American history. As we have seen, that is not strictly true. There were several men and women who amassed million-dollar fortunes before she found success in the emerging beauty industry. And there were other Black individuals and families who acquired significant wealth in the wake of Emancipation.

But Madam Walker was one of the most public Black millionaires in the Progressive Era, which saw the development of new opportunities for Black people in industry, the arts, politics, and the accelerating civil rights movement.

Born free in Louisiana as Sarah Breedlove, two years after the end of the Civil War, she was orphaned by the age of seven and forced to find work as a sharecropper and washerwoman. By the 1890s, she was married and had given birth to a daughter, A’Lelia.

She was also, to her distress, rapidly losing her hair.

In 1906, after developing her own hair-care products and business, Sarah Breedlove married Charles Joseph Walker, and was from then on known as Madam C.J. Walker. She had devised her own hair-growth formula by then, and was in a financially stable enough position to launch the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company.

Madam Walker always referred to herself as a “hair culturist.” She was sensitive to accusations leveled against her that she was trying to straighten Black women’s hair and change this fundamental element of their identity. But she never gave these accusations any weight. Madam Walker was a master of marketing and branding, constantly traveling with her husband and touring the U.S. so she could tell her own story. She also founded salons and beauty schools to train more “hair culturists” and provide Black women with a path to upward economic mobility. Her brand’s sole purpose was to help Black women grow and nurture their hair: She never wavered on this message.

By 1910, Madam Walker was running a full-blown factory out of Indianapolis to meet demand. Her daughter A’Lelia persuaded her to move to New York City, and she founded an office and beauty salon there that became a cultural fixture of Harlem’s Black community.

Between 1911 and 1919, Walker was at the peak of her career. Her company employed over 20,000 sales agents, as well as beauty school students and lab researchers. Her products were broadcast around the U.S. and Caribbean through aggressive advertising, allowing her brand to become a household name.

It was also during this time that Madam Walker became an active philanthropist. She organized her agents into state and regional clubs, launching an annual conference and association for them to develop business skills and contacts. She donated vast sums to the YMCA, Black churches, the Tuskegee Institute, NAACP, and a number of colleges.

Her friends included luminaries like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, and her daughter A’Lelia regularly hosted lavish parties in Harlem that were the envy of the entire city. Madam Walker and her family were generous with their fortune, but they also stood out from earlier generations in that they openly spent money on themselves (including by purchasing their own automobile!).

One of Madam Walker’s most ambitious projects was the construction of Villa Lewaro in Irvington-on-Hudson. The Italianate mansion cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and Walker commissioned New York’s first licensed Black architect, Vertner Tandy, for its design. It was a symbol of her achievement as a Black woman, and became a gathering place for some of the great artists and thinkers of the Harlem Renaissance, like Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes.

Unfortunately, she didn’t have long to enjoy the fruits of her labor. Madam Walker passed away in 1919 at the age of 51—only two years after beginning work on the Villa. Her daughter A’Lelia continued to manage the company and lead the high life between Harlem and Villa Lewaro (and later all over the world) before her own death in 1931.The Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company survived for decades until the trademark was sold in 1985. The Company never ceased to operate, however, and was eventually acquired and revived by Sundial Brands in 2006. Last year, Madam Walker’s great-great-granddaughter helped re-launch a new line of products, inspired by Madam Walker’s century-old legacy.

While this level of wealth was not shared by Black people everywhere, Madam Walker was proof that it was still possible, despite all the odds and setbacks she faced. The fact that a Black woman could now enjoy her self-made wealth publicly represented a fundamental shift in Black life.

The reality of Black wealth in America

Only two years later, the Tulsa Massacre in Oklahoma would show that, for many in the U.S., Black success still came at the expense of white supremacy. Over the course of three days, thousands of armed white men attacked the Greenwood district in Tulsa—known then as the “Black Wall Street”—razing 36 square blocks of a prosperous Black neighborhood to the ground. The damages, in 1921 dollars, were in the millions. Thousands of homes were destroyed. Hundreds killed. And many more displaced without homes or reparations.

White supremacists would continue, to this day, to terrorize Black communities and civil rights protests in cities all over the nation, from Chicago to Charlottesville. The examples of women like Mary Ellen Pleasant and Madam C.J. Walker might even have emboldened such racist violence. But they also proved to the generations of Black people who met and talked about them that there were paths to economic mobility, and that they had a right to it.

For me, their stories are a reminder that, despite the long way we have still to go in this country, perseverance and success are still possible in an inequitable society. If their entrepreneurial endeavors teach us anything, it’s that.

And they’re a reminder that, while Black wealth has been attacked for centuries, a new path forward has long existed in this country. My little girls are growing up in a world where they will see Black wealth being accumulated by entrepreneurs, executives, investors, doctors, sports and entertainment figures, and any other number of career paths. We can’t forget that the racial wealth gap persists, but it’s equally important to acknowledge that our children now believe it’s possible to acquire wealth and leverage it to make a positive impact in our communities.

That’s in large part thanks to women like Madam C.J. Walker and Mary Ellen Pleasant, who blazed the trail for us all.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the current status of the Madam C.J. Walker company.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.