When humans are cold, we put on a jacket—or bump up the thermostat. When we’re hot, we shed a layer—or bump up the air conditioner. But what if our buildings could do the same, on their own?

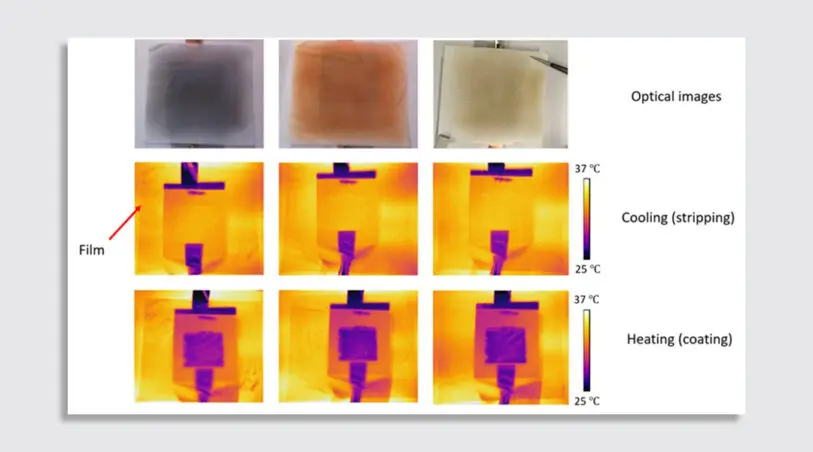

A team of researchers at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering have developed a building material that can change how much heat it absorbs and emits based on the temperature outside. Much like chameleons change the color of their skin to regulate their temperature, the new material, which consists of an ultra-thin film, can change its infrared color and ability to emit infrared heat, the invisible heat that radiates from people but also from the sun.

For example: When it’s very cold outside, the material can help keep the building warm by emitting only 7% of its infrared heat. When it’s very hot, it can keep the building cooler by emitting a whopping 92% of it. In theory, the system could be linked to your thermostat and whenever the temperature dips below, or rises above, a set number the system would use a tiny amount of electricity to automatically trigger the switch without you lifting so much as a finger.

This level of adaptability is made possible thanks to an electrochemical reaction. The material is only 0.5 millimeters thick, or 500th the width of human hair, but it consists of a fluid sandwiched between two solid layers. One of those layers is made of graphene (an ultra-thin layer of graphite, like the one that makes up your pencil lead). This highly conductive material is very good at transferring heat and electricity, but where the magic happens is in the middle fluid layer. This can take two radically different states: solid copper, which retains most of the infrared heat and acts like an insulating blanket, and a watery solution, which absorbs most of the infrared heat from your house then emits it outwards, keeping your building cool. The switch between the two states is where the chemical reaction occurs, triggered by electricity.

Some researchers are already working on smart windows that can switch back and forth between absorbing the sun in the winter and reflecting it in the summer. Others are developing windows that can change their opacity in minutes, like krill. But the material developed for this study can be applied on more than just windows. It can sit on any kind of surface, both inside your apartment and on the external façade of your building. For now, the prototype is a the size of a 6-centimeter square, or just over 2 inches, but as assistant professor Po-Chun Hsu, who led the research published in Nature Sustainability, explains, the material can eventually be turned into a sprayable solution, or the squares can be pieced together into a “quilt.”

Our buildings aren’t designed to adapt to the increasingly fluctuating temperatures caused by climate change. About 35% of a building’s energy use goes to heating, cooling, and ventilation, and greenhouse gas emissions from air conditioning will account for as much as a 0.5-degree Celsius rise in global temperatures by the end of the century.

Depending on where you’re located, the researchers estimate this material could make your building about 5 to 10% more efficient. Compared to some smart windows on the market, that number is pretty low, but what it lacks in performance (for now) it makes up for adaptability, and the ability to apply the material on walls and facades.

For now, the efficiency degrades after about 1,800 cycles, which is barely enough to last about three years of use (if you only change the temperature twice a day). Next milestone: 10,000 cycles, or however much it takes for the building to self-regulate itself as many times as it needs.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.