Maggie Paxton was 18 years old and days from finishing her second semester of college in late 2020 when she was killed by a hit-and-run driver while crossing University Avenue, a four-lane street bordering the University of Florida campus in Gainesville. A month later, a few blocks down the same street, two cars crashed and one spun into a group of students standing on the sidewalk; another student was killed and four others were injured.

These weren’t isolated incidents—over the last decade, dozens of crashes on the road have injured pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers. Several pedestrians have been killed, including, most recently, an 81-year-old man who died while crossing the same street one night last November. Some local critics call it death by design: The wide road was expanded in the 1970s to help cars move as quickly as possible, leading to more and more collisions. But the city has started making changes, including adding crosswalks with flashing lights and lowering the speed limit. And now, Gainesville will convert four miles of the road to a “complete street” with fewer, narrower lanes and a buffered bike lane.

Gainesville is one of hundreds of communities to get new grants from the federal government’s Safe Streets and Roads for All program to make streets safer. The grants, announced today, total more than $800 million, and include both funding for communities to plan new street designs and money to implement changes tailored to each location. In a neighborhood in South Los Angeles, for example, one new project will add curb extensions, raised medians, and high-visibility crosswalks. In rural Iowa, another project will add rumble strips and wider shoulders to help drivers avoid accidentally veering into ditches. The next funding opportunity, totaling $1.1 billion, will be released this spring.

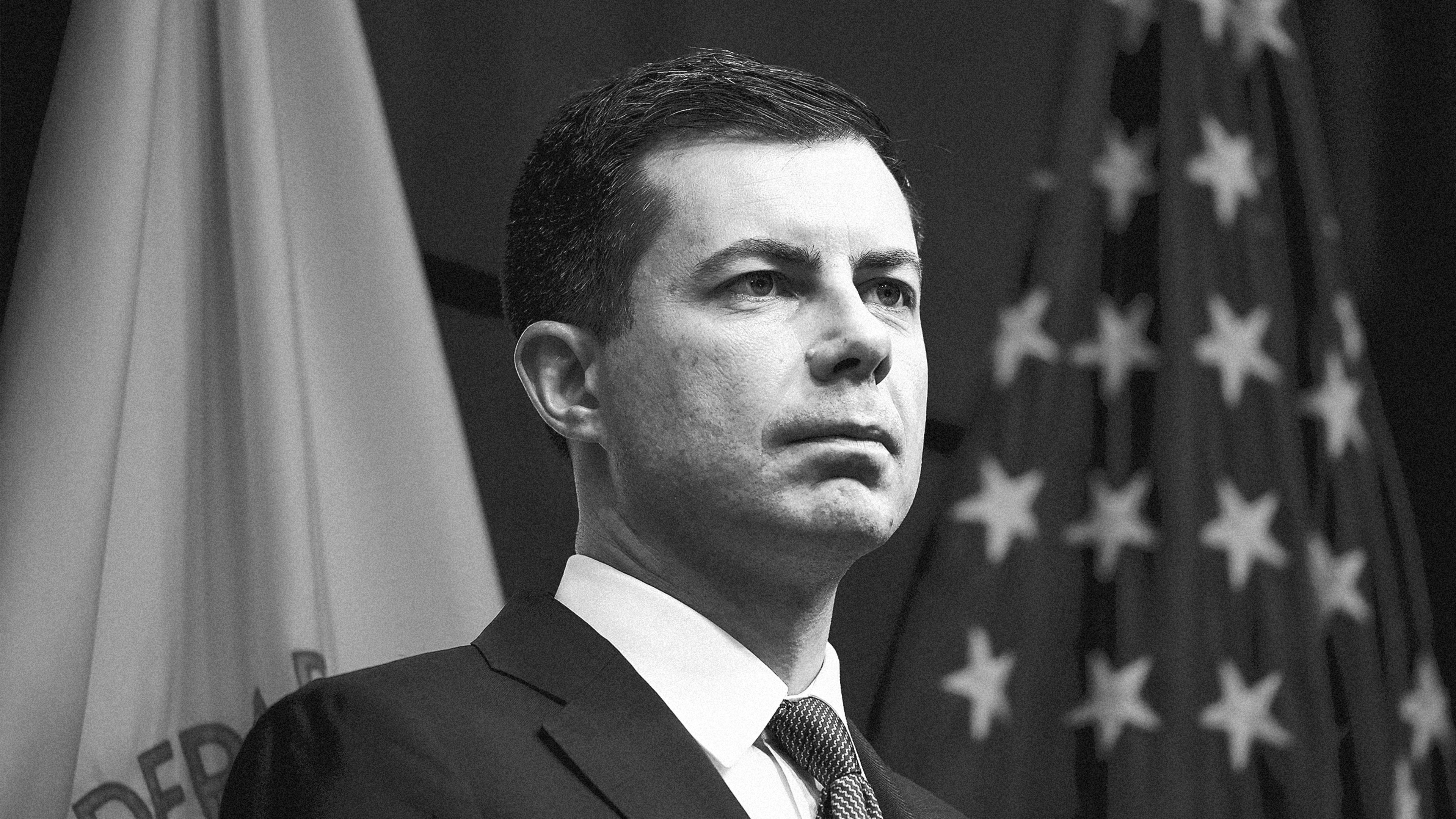

The work is one step in the government’s larger National Roadway Safety Strategy, launched last year, which ultimately aims for the goal of Vision Zero—completely eliminating traffic deaths. In Norway, which adopted a goal of Vision Zero in 2002, 80 people died on roadways in 2021; in the U.S., more than 42,000 people died in traffic deaths in the same year. (Oslo had zero traffic deaths in 2021, while 63 people died in similarly-size Portland, Oregon.) We talked to Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg about the overall challenge and how the grants can help.

Fast Company: The number of traffic deaths in the U.S. is shocking, but it seems like it’s been normalized. Why do you think it doesn’t get more attention? How did we get to a place where we take this for granted?

Pete Buttigieg: I think it’s precisely because it happens so much that we’ve gotten used to it. It’s almost as if we’re a population that grew up while a war was going on. It just became our reality. If I think back to high school, the kid who sat next to me in study hall freshman year and who sat in front of me in Spanish class senior year were both killed, and that’s just from four years’ worth of my life. I think most Americans can point to a rate like that of loss.

In its proportions, it’s on par with gun violence, about 40,000 people a year. But here’s the other thing, and we recognize this about gun violence, but not about roadway deaths: The U.S. is out of proportion with most other developed countries on roadway deaths. Not quite to the same level as gun violence, but enough to make it clear to us that these deaths are not inevitable—that this can change. That’s what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to start—before we get into the tactics and the technologies and funding—just getting Americans used to the idea that this is a preventable crisis, and that we don’t have to accept it, or think it’s just part of modernity or the cost of doing business.

FC: If you look at places that have been successful in reducing traffic deaths, like Norway, or cities like Hoboken, New Jersey, what are some of the factors that played a role for them to be able to implement Vision Zero?

PB: The first thing, which sounds abstract but is very important, is that they made a conscious choice to move in this direction. One of the reasons we’re advancing this idea of Vision Zero is not because we’re under any illusions that that can happen overnight. It’s because we’ve seen in very concrete terms that when a community or even a country adopts zero as the only acceptable level of traffic deaths, specific things happen as a consequence of that. It can actually lead to real measurable reductions. In the cases of these communities actually achieving zero, they demonstrate that this is not a pie in the sky goal. Of course, it’s not something that will happen overnight at a national level. But you know, whether you look at a city in the Nordic countries like Oslo, which has more than a half million people, or cities in the U.S. that are maybe a little smaller but with tens of thousands of people that also get this done—from a very dense community, like Hoboken, to more of a suburban community like Edina [Minnesota], it shows you that it can be done.

Specific steps they’ve taken include the design of their roads, which is one of the five elements of our national strategy: safer roads, safer people, safer vehicles, safer speeds, and better post-crash care. The speeds and the roads, of course, go hand in hand, because you can design roads in ways that encourage cars to drive safely and at a speed that’s appropriate to the context. And that’s a very big part of how, I think, these communities got results.

FC: Some other cities have set Vision Zero goals but haven’t had as much success. In L.A., for example, traffic deaths actually increased after they set their commitment. What are some of the challenges that you think cities face in actually implementing Vision Zero?

PB: We think that goal setting is important, but of course, it’s only the beginning. And every community has to find its particular strategy on how to get there. This is one of the reasons why even though we have a national strategy, the way we’re doing the safety funding is to fund local visions and local plans. Part of what we’re announcing is hundreds of local planning grants, each of which will be tailored to the needs of the particular community, as well as the three dozen or so places where we’re funding actual construction and implementation. First of all, [this strategy takes] funding, which is why we’re so pleased that President Biden’s package of infrastructure improvements includes this very real major federal commitment in terms of dollars.

Part of it is political will because it’s hard to persuade people that it’s worth changing something that we’re as committed to as the routine of our morning commute. I faced this in my own community, South Bend, [Indiana], where we did a conversion of a four-lane, one-way road that blasted vehicles through town into more of a complete street. People love it now and wouldn’t have any other way. But early on, it was tough, and it took a lot of selling, and frankly, a lot of listening to shape the plan toward what the community was ready for. It’s also largely a question, of course, of how drivers act. And I think that the bully pulpit that community and political leaders have is just as important as the funding and the engineering.

FC: As you’re giving out these grants, will you be gathering data about what’s most successful in particular locations?

PB: The data piece is huge. [We’ve plotted data with] purple dots all across the country to allow us to see partly where to target the interventions, but also, over time, where the results are happening. And a lot of these interventions are very data driven. We’re doing one in Prince George’s County, which is a largely underserved area near Washington, D.C., where they’re targeting specifically some of their highest injury spots. In rural Iowa, they found that about 60% of the fatalities and serious injuries had to do with lane departure. So what they’re going to do there is address the risk of people drifting out of their lanes with things like rumble strips and shoulder widening and relatively low-cost treatments that can make the difference.

In some places, it’s about the way crossings work. San Antonio is doing what are called islands—so basically in the middle of a block, where it takes a long time to get across, you have a place where pedestrians can take refuge. It’s elevated. Sometimes it’s things as simple as lighting. And other times it’s dramatic interventions that that really shift the way a road moves through the city.

FC: How far can changes to road design go on their own? Are these grants all looking at physical changes to infrastructure, or are some of them looking at things like speed limits?

PB: Speed is definitely part of it. And it’s not just how jurisdictions choose to set speed limits, but whether the design of the road encourages vehicles to observe those limits. Sometimes little visual cues or something like the width of a lane go a long way toward whether drivers feel kind of intuitively like they should be driving at the correct speed. There’s no one piece of it. There’s the road design, there’s behavior of drivers, and then there’s the vehicles themselves. That is a different side of what we do with USDOT but a very big one, and you’re going to continue to see us raising the bar on what we expect for manufacturers to make all vehicles safer. Importantly, not just for those in the vehicle, but for anybody who might encounter the vehicle, including pedestrians.

FC: In terms of vehicle design, as trucks and SUVs are getting bigger and heavier and more dangerous for pedestrians, what role do you think regulations can play?

PB: Any regulation that we put out has to be grounded in data, and so I think it’s important to do further research to look at how all the different trends in how vehicles are designed—their size, or composition, their weight, their proportions, even their shape—can affect safety. And that’s something we’ll continue to look at, in addition to the more familiar vehicle features like seat belts and airbags and the next-generation features like automated or advanced driver-assistance systems that hold a lot of promise for safety, but haven’t fully been proven yet.

FC: I’m also curious what you think the potential is for “speed limiters”[software in cars that can recognize the speed limit and restrict the top speed as someone drives]. I saw that New York City is starting to test this in its own fleet. Do you think that could be something that the government requires in new vehicles?

PB: Certainly with regard to industrial and commercial fleet trucking, that’s a very active conversation. You don’t see that as much in the conversation for privately owned vehicles. We do have to make sure that jurisdictions and designs are supporting safe speeds.

FC: Are there any last thoughts you’d like to add about the next steps?

I’m really excited to see the results of these planning grants that we’re funding around the country because those will go not only to engineering and designs on paper, but actually will go to some prototyping, where you can do some tentative or temporary measures to see how something will work. I think we’re going to learn a lot in the next few years. And we have to urgently put those learnings to use because, again, the status quo just can’t continue.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.