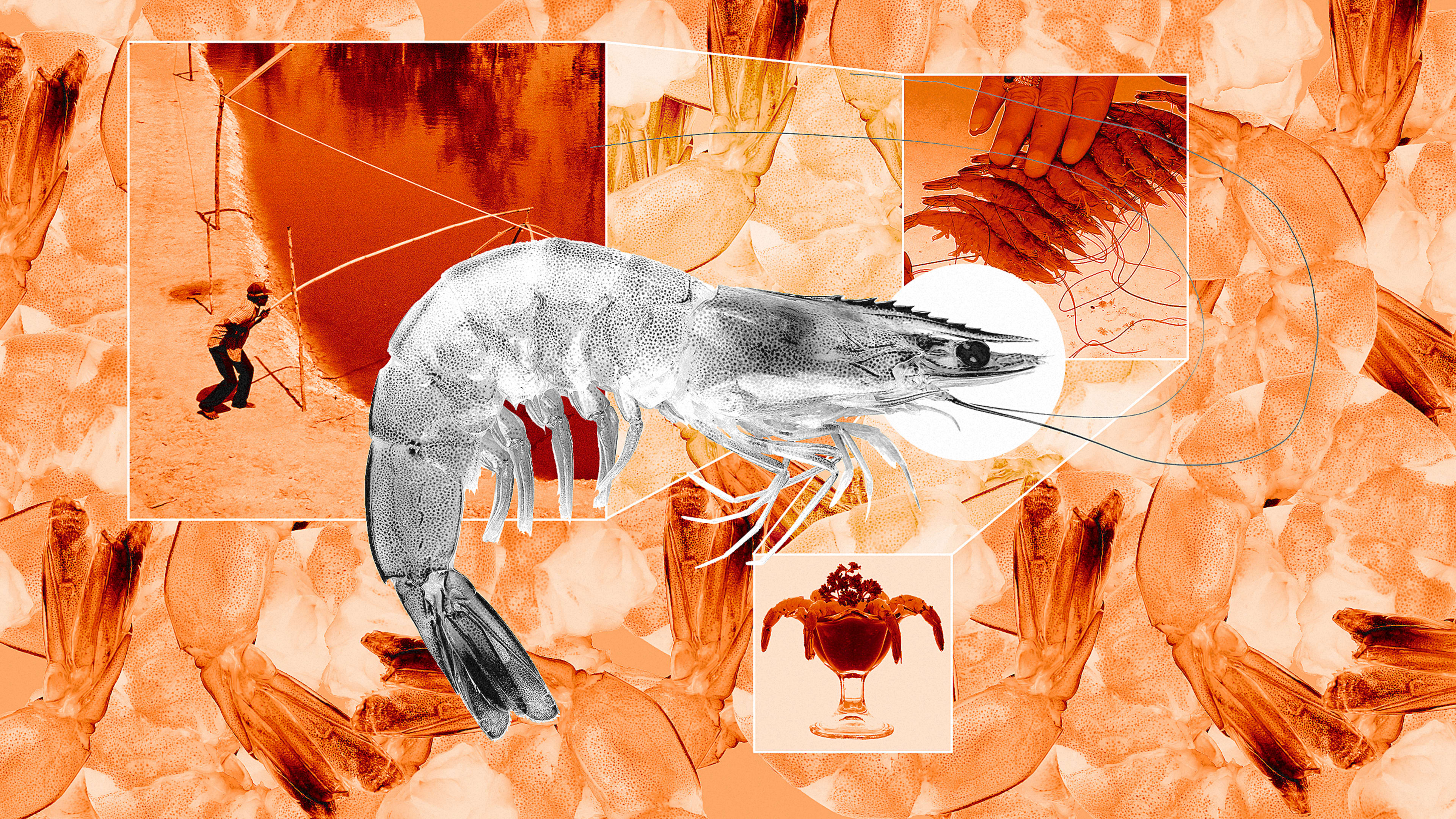

If you rang in the new year with some shrimp cocktail in hand, you weren’t alone. Shrimp is the most popular seafood among Americans, with industry groups reporting that we eat about five pounds of shrimp each year, per person. We hear a lot about the negative effects of industrial animal agriculture on our planet, not to mention the animal cruelty inherent in it— but these conversations are almost invariably focused on land animals raised as livestock, particularly cows and chickens. If seafood seems to have an eco-friendly halo by contrast, that’s probably more due to our own educational blind spots than any true environmental superiority. Despite their small size, shrimp carry some major ethical baggage that includes the destruction of critical environmental features as well as horrific human rights abuses and chilling acts of animal cruelty.

A major reason we’re able to eat as much shrimp as we do is that it’s much more affordable and accessible than it was half a century ago, and for that, we have aquaculture—the farming of seafood—to thank. About 90% of the shrimp sold on the U.S. market is imported, primarily from shrimp farms in Southeast Asia, where commercial shrimp farming took off starting in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The industry grew exponentially over the next several decades, giving us modern marvels like all-you-can-eat shrimp specials.

But endless shrimp comes at a cost, and the first and most visible sacrifice was of the world’s mangrove forests. Between 1980 and 2012, an estimated one-fifth of mangroves, globally, were destroyed to make room for commercial shrimp farms in brackish coastal areas, according to the U.N. Over a decade later, mangroves are still a major concern, and UNESCO warns us that “time is running out” to protect them. More than just a beautiful natural sight, mangroves provide important services to their ecosystems—they absorb the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, and they also act as a barrier to protect coastal lands from natural disasters and other threats.

In his 2016 book Blood and Earth: Modern Slavery, Ecocide, and the Secret to Saving the World, Kevin Bales explains that cyclones are a regular occurrence in the Bay of Bengal, and mangroves provide a buffer that save thousands of human lives. Repeatedly throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, mangrove forests dramatically lowered the death count from natural disasters as compared to areas where the mangroves had been significantly or entirely depleted. When the 2004 tsunami hit the shrimp farming coasts of Burma and Thailand, where over 80% of the mangrove population had already been desiccated, the human death toll was around a quarter of a million. In Bales’ words, “put simply, without the mangroves, people die.”

The people living in those regions, though, are commonly subjected to more direct forms of harm and exploitation for the sake of the global shrimp industry. The other ugly, not-so-secret truth about shrimp farming is its close ties to slave labor, especially child slave labor. Shrimp farming, peeling, and other industry operations in and around Thailand have been consistently discovered using the labor of enslaved people, mainly migrants from Burma and Cambodia, to produce shrimp that will eventually end up being sold at major U.S. retailers. Slave labor is so deeply embedded within Thailand’s seafood export industry that human rights advocates say the industry would probably collapse without it. Similarly, research affirms the continued role of slave labor in Bangladesh’s seafood industry, where already impoverished families are taken advantage of by traffickers offering ostensibly legitimate work. The people formerly enslaved by these operations report witnessing and living under threat of graphic violence and working alongside children too small to even reach their workstation. And despite numerous investigations breaking over the past decade, the widespread and opaque nature of the global shrimp industry makes the issue of slave labor difficult to trace, let alone abolish. To this day, it’s virtually impossible to know with certainty where most farmed shrimp came from, and who labored to bring it to you.

There’s one more victim in the shrimp production process, and that’s the shrimp themselves. It can be harder for us to extend empathy to animals whose bodies don’t look or work like ours, but there is evidence to suggest that crustaceans—including shrimp—are capable of experiencing pain. Even invertebrates possess nociceptors, special sensory receptors that respond to extreme temperatures, injuries, and other potentially harmful stimuli. Robert Elwood, a British biologist based at Queen’s University Belfast, who has worked with shrimp in the lab for decades, has argued that the reactions shrimp exhibit to painful stimuli goes beyond mere reflex— they groom and pay special attention to wounded areas in a way that strongly suggests self-soothing behavior. Furthermore, the fact that they respond to opiates and other painkillers implies that they are capable of feeling pain in the first place. If we concede that it’s at least possible that shrimp feel pain, some common practices in shrimp farming take on a dark specter. Unchecked water pollution can lead to weakened immune systems, and in extreme cases, death by asphyxiation or poisoning; high population densities in shrimp farms contribute to the spread of disease among the living crustaceans.

But perhaps the ugliest animal welfare issue in shrimp farming is the practice of eyestalk ablation. Shrimp farmers in the industry’s earlier days discovered that removing one or both of the eyestalks from female shrimp encourages reproduction by inducing maturation of the ovaries, for reasons most likely related to the release of hormones. In the process of eyestalk ablation, which is still widely practiced on shrimp in commercial and research settings today, female shrimp have their eyes cut without anesthetic. Ultimately, be it from the physical trauma, the disorientation that comes from sudden vision loss, or other related factors, ablation has deleterious effects on a shrimp’s growth and eventually leads to reduced egg quality and heightened mortality.

Despite all of the above, Americans really like shrimp—and if there’s anything we know, it’s how hard it is for people to change their eating habits, especially when it means giving up something they love. The good news is that vegan seafood alternatives have made some serious strides in recent years.

While names like Tofurky have been part of our cultural lexicon for decades, plant-based shrimp has been much less common and, frankly, much less tasty. That’s changing, thanks to a handful of forward-thinking brands that are putting out their own shrimp-inspired products that look like the orange-pink curls we know and love, without any of the cruelty to humans or marine life. Sophie’s Kitchen has breaded shrimp already available for purchase at major retailers like Wegmans and Whole Foods. The Virginia-based Plant Based Seafood Co. has two shrimpy options for sale: their classic “dusted” shrimp and the retro favorite coconut crusted shrimp. These new-wave vegan shrimp are made purely of plant ingredients, like konjac root, rice, and wheat, so no one with shellfish allergies need be left out.

Perhaps even more exciting, though, are the developments being made in cell-cultured shrimp. Bold new startups like Singapore’s Shiok Meats and South Korea’s CellMEAT have been pursuing funding—and receiving it, to the tune of millions of dollars—to develop and scale up their production processes. Cell-cultured meat, sometimes also called lab-grown meat or cultivated meat, is when cells that are genetically identical to animal protein are grown outside of an animal, with little to no animal inputs. Shiok Meats has been successfully courting investors with private tastings over the past few years, and working on scaling up their production and productivity in order to drive prices down. At this rate, it wouldn’t be a shock to see their products hit shelves sometime this year. CellMEAT’s technology is proprietary, but all signs look promising: their most recent estimates place their production costs below $20 per kilogram of shrimp meat. Although this is nearly double the cost of conventional shrimp, that’s still no small feat—a dramatic reduction in price is precisely what has fed the United States’ appetite for shrimp this last half-century. If cell-cultured shrimp ultimately becomes affordable and widely accessible, it stands a chance to blow up the seafood market as we know it.

Shrimp is a beloved food, but those tiny crustaceans wouldn’t have such a significant place on our plate if not for the human rights abuses and environmentally destructive practices that make them so cheap to produce. If we want to keep enjoying one of our favorite seafoods without being complicit in human trafficking and other heinous practices, we’re going to need to be more mindful about how much we’re consuming and where we’re getting it from. Fortunately, shrimp alternatives are more viable than ever. Culinary minds and food technology are convening to make sustainable, ethical alternatives to shrimp a reality. Chances are it won’t be long before we start seeing alt-shrimp in stores and at the most cutting-edge restaurants—and that’s something to celebrate.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.