On a recent weekday afternoon, a team of engineers watched as a small robot hovered in the clear water of Canada’s Georgian Bay, gently picking up rocks off the sandy bottom. Impossible Metals, the startup that designed the robot, wants to prove that it can sustainably harvest deep-sea metals like the cobalt and nickel needed for electric vehicle batteries. The test in shallow water was its first proof of concept. Still, scientists question whether it’s possible for any deep-sea mining to avoid harming the environment.

Deep-sea mining is on the verge of becoming a reality: Some companies could begin operating as soon as next year, extracting minerals that have naturally collected thousands of feet underwater. Marine biologists say it could be an environmental disaster. Most companies plan to use huge machines to dredge the ocean floor or drill into underwater mountains, disrupting unique ecosystems.

“Some scientists describe them as being the most vulnerable places on the planet,” says Douglas McCauley, an ocean science professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The cold, dark environment is home to fragile species. Deep-water coral, for example, can live as long as 4,000 years. If the habitat is destroyed, the ecosystem can’t easily come back.

Digging and dredging the ocean floor could create plumes of sediment that drift through the water, smothering marine life and releasing toxins like mercury that could end up in the food chain. When mining companies bring rocks to the surface to process them on ships, the waste will be dumped back into the water, creating more poisonous plumes. The disruption could affect the fishing industry. It would also release carbon from the ocean floor.

“We’ve never tampered with that before,” McCauley says. “And the world would perhaps best be served by leaving carbon that’s stored in secure places stored in secure places.” While scientists are still researching the problem, one study estimated that disrupting the seafloor could potentially release as much carbon as air travel.

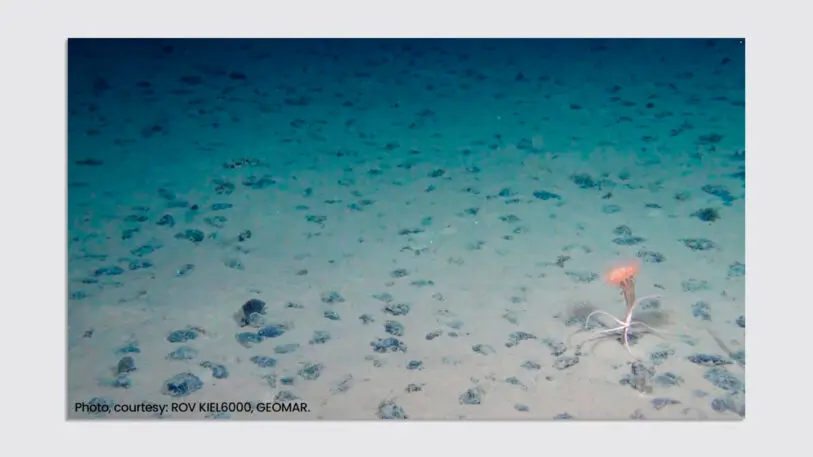

Most mining companies plan to work first in the ocean’s abyssal plains, where potato-shaped “nodules” filled with valuable minerals sit on the ocean floor. (The nodules form over millions of years as minerals build up around debris like a fish scale or shark tooth, aided by the intense water pressure and the temperature and water chemistry.)

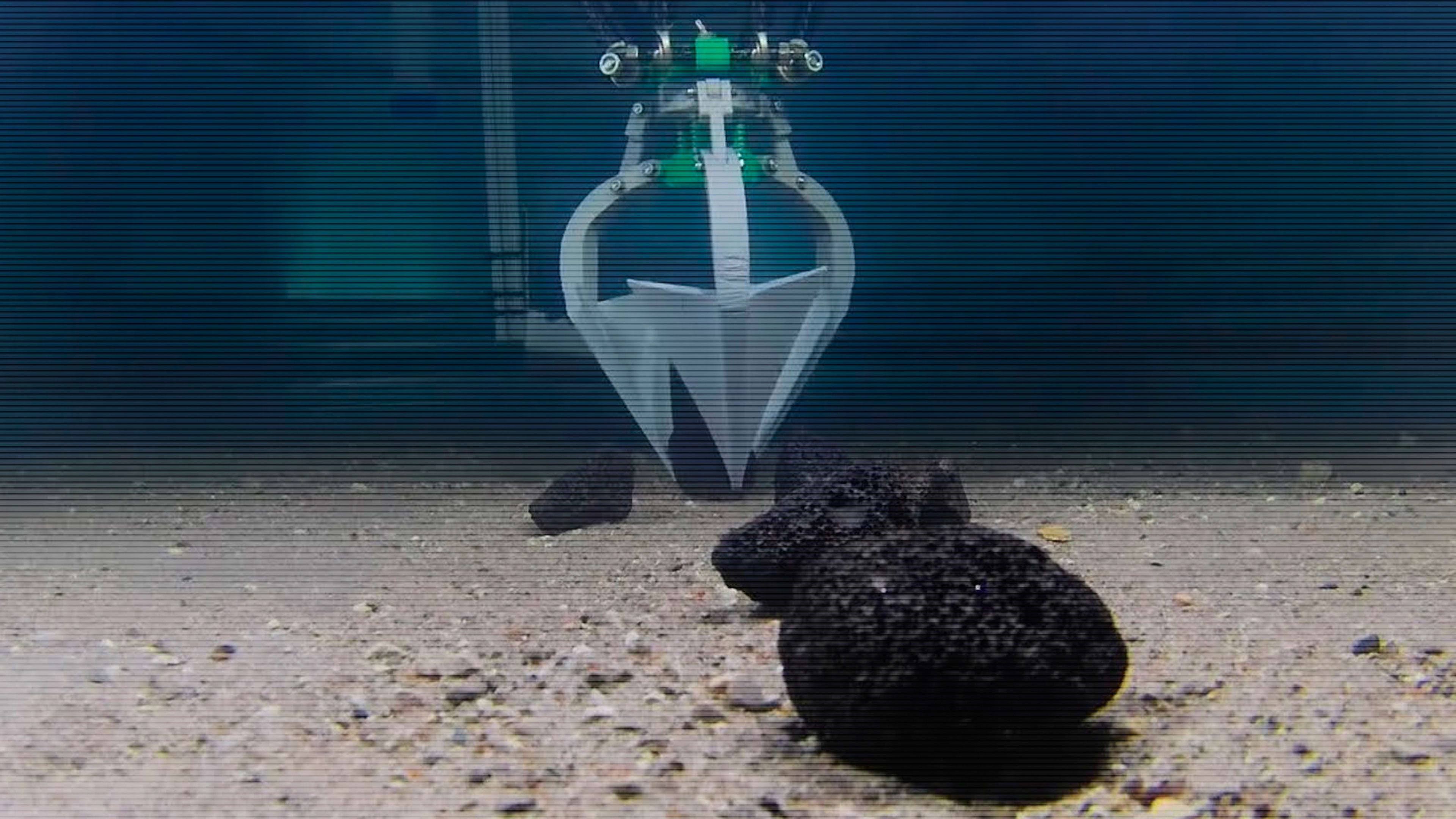

Instead of dredging up these nodules, Impossible Metals plans to use its robotic vehicles to pick them up, creating as little disturbance as possible. The robots will use artificial intelligence to identify any marine life resting on the rocks, and avoid picking those up; the company says it’s also working with scientists to plan how many of the nodules to leave in place as habitat.

“Because we have that selective harvest ability, we can leave habitat corridors and different densities behind in order to ensure that we don’t have a loss of biodiversity,” says Jason Gillham, the startup’s chief technology officer and one of its founders.

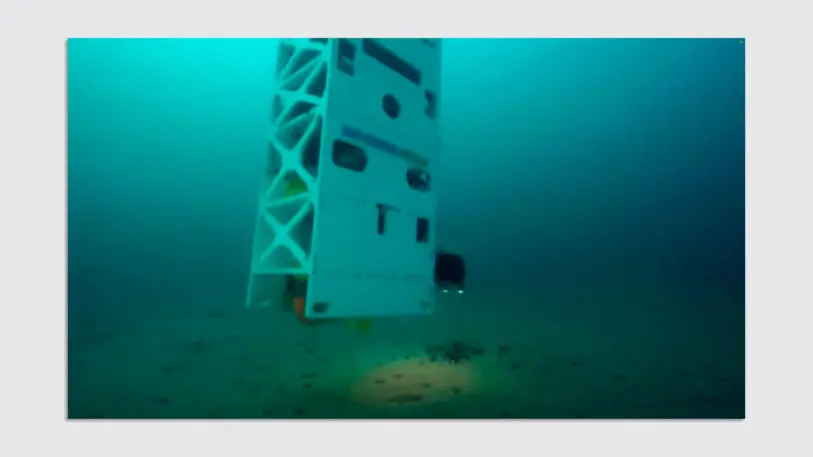

Impossible Metals plans to use fleets of large autonomous vehicles, each roughly the size of three shipping containers, with hundreds of robotic arms. While any vehicle moving through deep-ocean water can create sediment plumes, the engineers are working on a design that will move smoothly to minimize that problem.

After the rocks are harvested, the company also plans to use a new system to extract the metal at a facility offshore, making use of naturally occurring bacteria to dissolve the rocks into a solution. The team believes that its process will avoid generating the toxic waste that typically comes from mining, and it will also use far less energy.

Environmentalists argue that all of this still isn’t enough. “I don’t think they can do it completely without harm,” says Arlo Hemphill, the deep-sea-mining campaigner for Greenpeace USA. Sediment plumes are still likely, he says, and the habitat will change, even if the company works carefully. It’s also likely to be difficult to detect some of the marine life living on the rocks.

“If deep-sea mining was already an entrenched industry that was doing damage all over the world, and we’ve been doing it for 100 years, and somebody like Impossible Metals came along with these ideas to do it [with less harm], I would probably applaud that,” he says. “But we’re in a completely different place. The problem hasn’t started yet. And we don’t have to start.”

It’s still possible—though perhaps unlikely—to avoid letting any companies enter the space now.

The mining industry argues that it’s critical to access more metals for the lithium batteries used both in electric cars and for storing renewable energy. But environmental advocates like Hemphill point to the fact that new battery technology can reduce and eventually eliminate the need for some of these materials. For example, a startup launched by an engineer who previously worked on Apple’s EV project is designing long-range batteries that cut out nickel and cobalt. Battery recycling is also scaling up and can provide some materials without the need for new mining.

An obscure organization called the International Seabed Authority (ISA) has control over what happens in international waters, and plans to issue permits to deep-sea-mining companies to begin working as early as July 2023. Tests have already begun; a miner called The Metals Company recently spent eight weeks collecting 3,000 tons of nodules from the Pacific Ocean. Since Impossible Metals is still developing its technology, it likely wouldn’t begin operations until at least 2026.

Political pushback began this year, as countries including Germany, France, New Zealand, Fiji, and a handful of others have called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining because of the risks. Though the ISA governs itself, members of the United Nations could vote to ban the mining if there is enough opposition.

Right now, the ISA listens mostly to mining companies, McCauley says. “The only folks that are turning up at the ISA are those that want to make money off of mining that space. The perspective of fisheries and the perspective of marine scientists is not being captured there,” he says, adding that hundreds of marine scientists recently signed a statement calling for a moratorium—so far to no avail.

But mining projects could also be stymied by economics, as a growing list of companies, from BMW to Samsung, have said that they won’t buy deep-sea-mined materials. “It could become an economically unprofitable exercise,” McCauley says. “That could happen and seems to be happening right now, because these buyers that they’re trying to mine for are saying, ‘We don’t want your material.’ Demand will not be there.”

Correction: We’ve updated this post to correct the name of The Metals Company.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.