As soon as Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, cultural heritage specialists around the world could see what was coming next. In addition to bracing for the death and carnage of modern warfare, the global community of archaeologists, historians, and cultural sector workers prepared for the likely devastating impact the war would have on Ukraine’s historic monuments and resources. “We know that one of the tactics of war, especially for invaders, is to target heritage sites, because that’s what breaks the fabric of any culture,” says Nada Hosking, executive director of the Global Heritage Fund, a San Francisco-based nongovernmental organization.

GHF launched an international effort to track and monitor the country’s most important cultural resources. Information about threatened or destroyed objects and spaces—from prehistoric archaeological sites to public monuments to treasures held in historical museums—is now being gathered through detailed satellite imagery, informal reports, and on-the-ground confirmation by cultural heritage professionals.

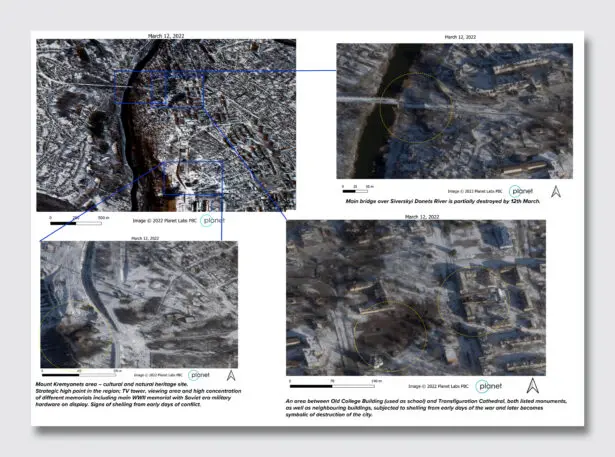

Funded in part through a grant from the International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas, the effort has been aided by Planet, a satellite imagery provider that’s given researchers high-resolution images of places under threat.

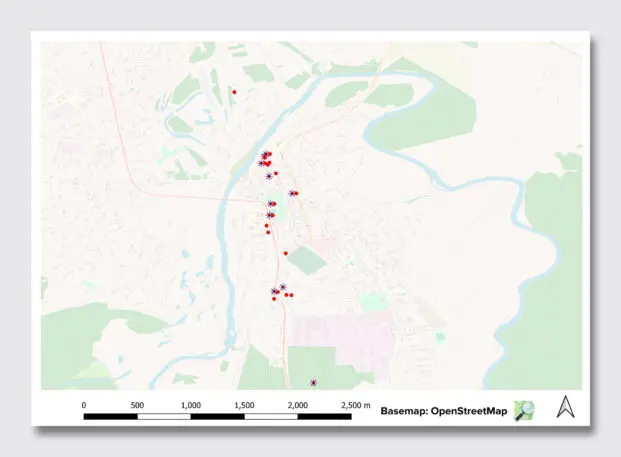

Remote researchers in multiple countries are guiding the process and creating a detailed open-source geographic information systems, or GIS, database. Crucially, the project is also assisting Ukrainian cultural sector workers on the ground in active war zones to collect information and verify reports of damage. These informants are being supported with small stipends, as their day jobs have been put on pause, and they’re persisting in collecting this data despite great personal risk.

The database is intended to protect and stabilize artifacts, buildings, and monuments as the conflict drags on, and also to aid government ministries in the eventual recovery and restoration work that will have to happen whenever the war ends.

“In the past this kind of information was done top-down by experts from the government, on paper, and you’d never see it,” Hosking says. “I think owners and stakeholders and communities should have access to it and should be able to participate in the protection as well.”

Gai Jorayev is an archaeology professor at the University College London who is leading the analysis of the satellite imagery and coordinating the information being collected on the ground in Ukraine. When the project started, he’d assumed most of the observations would be focused on the rural places where Ukraine’s archaeological sites tend to be. But once the war had been underway for a few weeks and reports were streaming in about the imprecision of Russian weapons, Jorayev says the project evolved.

“It became clear that almost everywhere [the Russians] go there will be destruction,” he says. “So we started focusing on areas where we had the in-depth knowledge of our Ukrainian colleagues.”

The work has since centered on the urban areas of Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Kharkiv. Working with archaeologist Tatiana Krupa, a native of Kharkiv now based at Pavlodar Pedagogical University in Kazakhstan, the researchers have developed a roster of historians, archaeologists, museum workers, and others in the cultural sector to provide the kind of detailed information they and other professionals will need to perform restoration after the war is over.

“Ukraine will need extensive assistance in rebuilding,” Krupa says. “Specialists will need high-quality analytics, and not just streamlined statements. That is why we are doing this work.”

Jorayev says the project is showing the importance of combining remote and local observations, explaining, “There are events which we know about from reports of local colleagues, but we can’t really see traces of it on satellite imagery because simply the resolution is not there.”

Using open-source GIS technology, Jorayev and his colleagues are compiling satellite and photographic imagery of damaged sites, firsthand and press accounts, as well as precise coordinates. The maps they’ve produced track reported destruction and shelling alongside the locations of known monuments. He says the original hope was that the Ukrainian cultural heritage workers on the ground would be able to collect and enter the information online, but internet access and technology challenges have led the project to pivot. Now most information is coming in through WhatsApp and text messages that he and his colleagues compile into their GIS database.

Some of these messages are detailed descriptions of monuments that have suffered shelling, while others are almost like reports from specially trained covert operatives out behind enemy lines. “On occasion we’d receive a message saying there are things happening that aren’t being reported anywhere else. For example, museum advisers were sent from Russia to assess the museums in some occupied areas,” Jorayev says, pointing to the potential for cross-border looting. “That’s the type of information you wouldn’t know even if you were on the ground, unless you are a heritage specialist specifically focusing on that particular museum.”

One of the workers helping to ground-truth damage reports and follow up on the shelling seen in satellite imagery is Elena Evgenievna, an archaeologist based in Chernihiv, a city near Ukraine’s northern border with Russia and Belarus. She says museums in the area have struggled to keep their collections protected during the conflict, partly due to lack of resources. She points to the Chernihiv Regional Art Museum where “the most valuable paintings were managed to be hidden by employees. The director and custodians worked during shelling and air raids. But those paintings that remained in the halls were pierced by fragments.”

Evgenievna, who works at the Tarnovsky Chernihiv Regional Historical Museum, says the damage is not just the fault of the Russians, but also institutions and levels of government that were not prepared for such extreme circumstances. She notes that some damaged monuments in cities could have been protected early on with simple sandbags, for example, and the national government has not yet incorporated as legislation UNESCO’s 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.

“The question is not Who is to blame? The question is What was not done and why? There are a lot of questions,” Evgenievna says, “and getting answers to them is very important to avoid repeating the current situation in the future.”

Jorayev says many informants in Ukraine have noted similar challenges, with local institutions having few protocols for protecting their collections. Many were left scrambling to safeguard items using limited resources in the early days of the invasion. But he also notes that wartime considerations aren’t typically top of mind for many in the cultural sector. “Nobody really goes into the heritage world thinking My museum will be bombed in the next five years,” he says.

Elena Borisovna is head of funds for the Odessa Archaeological Museum, which she says was slow to photograph and digitize important documents. To do better, she says museums need higher standards—and more government oversight. “The [culture] ministry must establish a supervisory body, which, in the event of an emergency, will ensure the protection of cultural heritage,” she says.

In the meantime, this information-gathering effort, along with several other similar projects by groups such as the Smithsonian, are laying the groundwork for the rebuilding and restoration of Ukraine’s cultural heritage. Hosking says this approach has worked in the past, including in Beirut, where volunteers quickly collected a vast amount of information about buildings damaged by the August 2020 port explosion. “They managed to document about 200 buildings in the span of three days just with their phones,” Hosking says. “That data went to [the] directorate of antiquities. That’s what they’re using for the rebuilding process.”

Hosking says the project in Ukraine was originally planned to run only through the end of November, but the work may have to continue as the war drags on. “Unfortunately it’s an ongoing issue that doesn’t have an end in sight,” she says. Jorayev expects the database to eventually be handed over to Ukraine’s culture ministry, but there is currently no timeline for that to happen.

Evgenievna in Chernihiv acknowledges that while human suffering is the worst part of the war, damage to cultural heritage sites is also abhorrent. Protecting these sites, she says, is protecting “the basis of our collective memory of the past.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.