Walter Gropius, one of the leaders of the early 20th-century modernist movement in architecture and a founder of one of the world’s most important schools of design, was a cowboy at heart. Before founding the internationally significant Bauhaus design school in Germany or bringing a new humanity to the design of industrial buildings, Gropius was shaped by a boyhood encounter with the Wild West showman Buffalo Bill Cody.

As a 7-year-old boy in Berlin, Gropius went to see the European tour of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, a spectacle of “cowboys-and-Indians” roleplaying and horse riding in elaborately themed sets. This exaggerated version of the American frontier experience sparked a lifelong fascination with the United States and its cowboy history. For someone later associated so inextricably with the clean lines and functionalism of modern design, it’s a surprisingly rustic influence.

This detail and other unexpectedly playful elements are unearthed in a new book, Walter Gropius: An Illustrated Biography, by Leyla Daybelge and Magnus Englund.

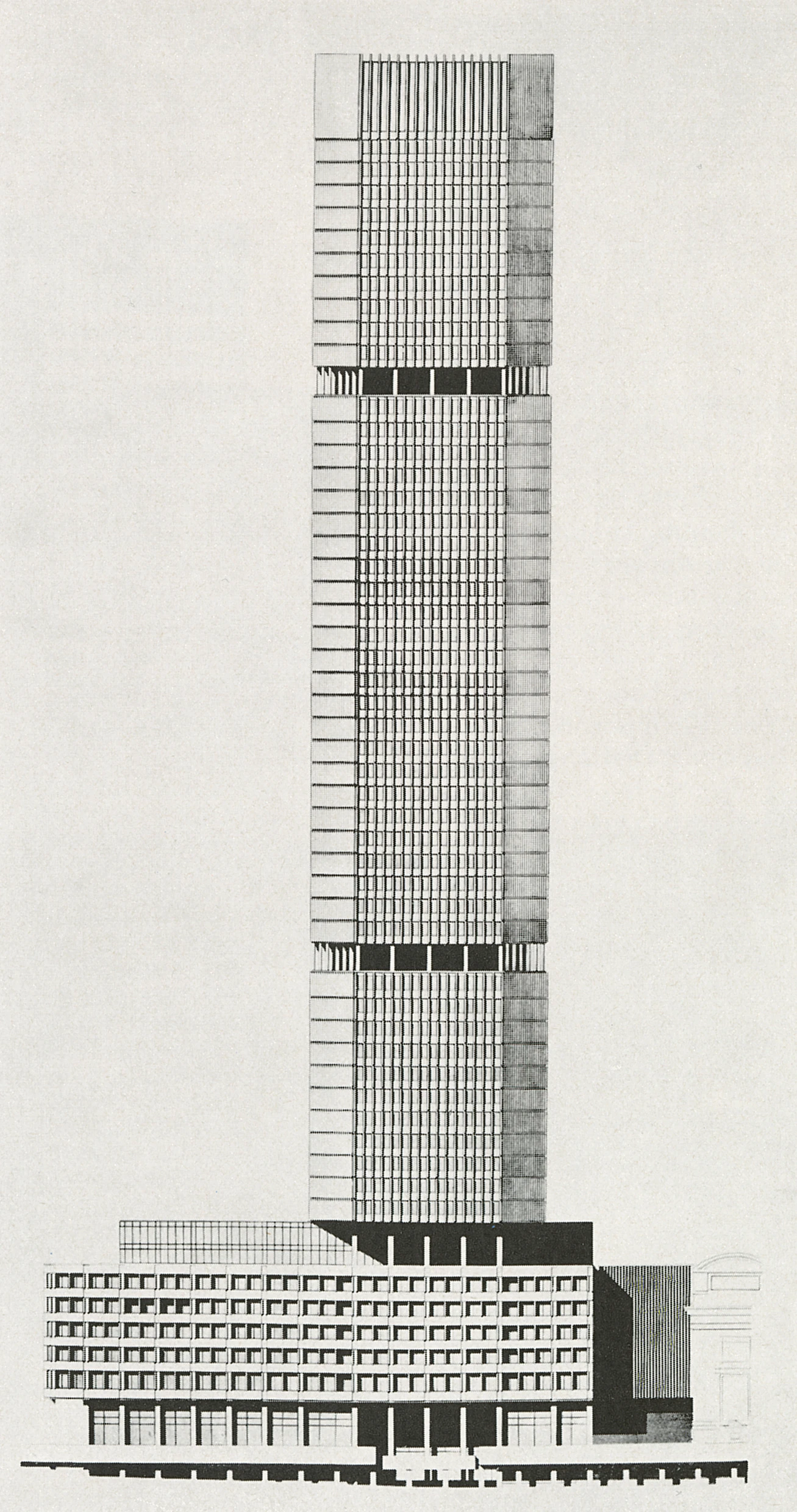

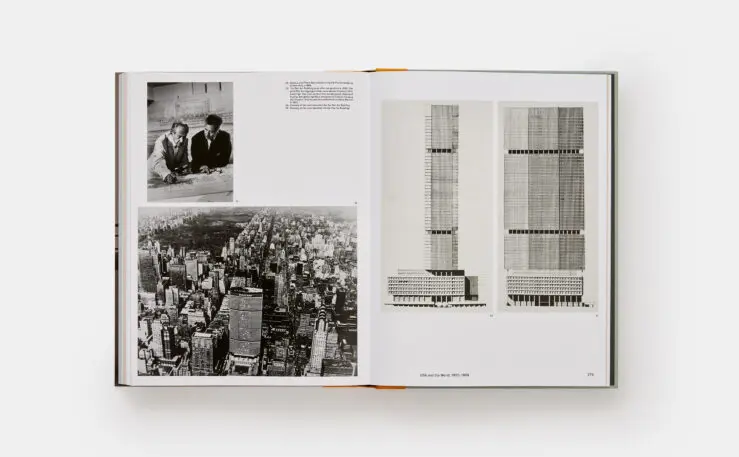

Gropius’s life is a movie waiting to happen. In his late 20s, he reinvented the industrial aesthetic, with a glass-walled shoe factory designed in 1911. Then, fighting for the Germans in World War One, he was nearly killed several times, and once had to claw himself out of a hole after being buried alive for three days. He later went on to found the still influential Bauhaus design school in 1919 before fleeing Germany under the rise of the Nazis. He kept the flame of modernism burning in the U.S., where he became head of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, teaching future giants of architecture including Philip Johnson and IM Pei. He also had a turbulent romantic life, including an ill-fated affair with the wife of composer Gustav Mahler. All throughout, he was designing notable buildings around the world, including the Fagus Shoe Factory in Alfeld, Germany, the Bauhaus school building in Dessau, Germany, the Pan Am building in New York, and the American Embassy in Athens. “His life mirrored that great rollercoaster of 20th-century history,” says Daybelge.

Gropius’s claimed that he lived three distinct lives—as an architect and educator in Germany before and during the rise of the Nazis, in London for three years in the 1930s as an exile, and as an elder statesman of modernism in the U.S. for three decades. Daybelge and Englund argue in the book that Gropius lived many more lives that that. Here are a few.

Architect ahead of his time

Gropius’s most famous architectural design is his Bauhaus building in the school’s second home, Dessau. Daybelge says the design, with its glass-lined walls and iconic signage, remains famous for a reason. “Now nearly 100 years old, it’s astonishing how contemporary that building is, and how when you go inside it isn’t clinical, it isn’t cold,” she says. “It’s unexpectedly timeless.”

Team player

Early in his career, Gropius worked alongside architects who would go on to become some of the biggest names in design, including Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. But unlike these towering and famously egotistical figures, particularly the self-named Le Corbusier, Gropius spent his entire career working in conjunction with other designers, eschewing sole credit or fame for a better design. “Even though I’m sure he had a really strong personality and probably a strong ego, he keeps collaborating with other people all the time,” says Englund. “That sets him apart from those other big names. He always worked as part of a team.”

Political agitator

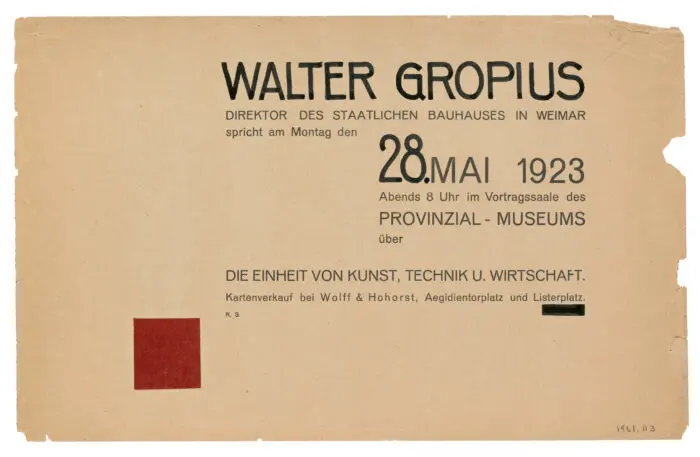

In establishing the Bauhaus school and fostering its expansive view of the way design could improve people’s lives, Gropius saw design as a tool for social and industrial progress. Throughout the 1920s, the politics of Germany were increasingly at odds with this view, threatening first the funding of the Bauhaus and later its entire existence. Like many of his contemporaries, Gropius eventually fled the fascist regime rising there.

“As he’s about to leave Germany he writes letter to the Nazi authorities saying ‘don’t you understand what you’re doing? You’re losing modernism. If you carry on this way, it’s going to be the Americans that carry it on and run with it,'” says Englund. “And that’s exactly what happened.”

Gropius, too, went to the U.S. in the late 1930s, as much fleeing the Nazi regime as following the potential of modernism to redesign the world. “I think it was deeply, deeply personal for him,” says Englund. “He shared with a lot of other people of his generation that he had this vision of a better future, which is not always the case today.”

Aspiring American

Before fleeing to the U.S., Gropius visited as a tourist in 1928, starting in New York. “He wants to visit every skyscraper that’s under construction,” says Daybelge. The trip was largely an architectural tour, seeing new forms of buildings, from the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge factory outside of Detroit to the modernist apartments Richard Neutra designed in California. He even took a side trip to Arizona, riding down the Grand Canyon on horseback, wearing a cowboy hat.

Daybelge says Gropius held on to this American fascination for decades, long before moving to Massachusetts for his Harvard post. “That began with Buffalo Bill,” she says. “We can trace it through his entire life, even down to the little collection of cacti on the window that he kept in the [Bauhaus] director’s house in Dessau.”

This American dream lived on in Gropius until his death in 1969. “Just a year before he passes away, he’s in Arizona on horseback,” says Englund. “And with a Stetson hat on his head.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.