On a formerly vacant city-owned lot in Tempe, Arizona, not far from the campus of Arizona State University, a rare type of housing development has just been built. Unlike the abundant rental housing geared toward the college crowd or the sprawling single-family homes filling subdivisions across the region, the new project eschews size and profit to offer something almost impossible to find there: small homes oriented around a shared courtyard, offered for sale at permanently affordable prices.

The 13-home project is an example of an old way of building, updated for the modern age. Twelve of the houses are identical 600-square-foot, lofted one-bedroom homes. The other is a single-story home that’s compliant with the Americans With Disabilities Act. All share a central green space, a 900-square-foot common room, and a communal kitchen. Priced for sale to those making less than 80% of the area’s median income, the homes are a throwback to a time when homes didn’t need to be big and expensive.

“The idea of doing a small group of homes around a central courtyard is really a historic way that America grew. And then we got away from it,” says David Crummey, project manager of Newtown CDC, the Tempe-based nonprofit organization that developed the project.

Bungalow courts, or cottage courts, were found in nearly every major city in the early part of the 20th century, but the market has gradually edged away from that compact form of housing. “With the consolidation of the mortgage market and the increase in the number of large subdivisions, small-scale development has really, really fallen off the chart,” Crummey says.

When it comes to for-sale housing that’s affordable, the bungalow court makes a lot of sense, he says. Without the need for an entire expensive lot, or the parking and street access of the typical car-oriented project, houses like these can be built at much lower cost.

For Crummey, whose organization typically does single-family home rehabs to sell to low-income first-time homebuyers, this so-called micro-estate project seemed like a way to do more with less.

The project began in 2015 as a student design exercise. Undergraduate engineering students at ASU were assigned to come up with ideas for housing on city-owned lots, and one project proposed turning this space into a tiny home village. Officials in the city saw the proposal and liked it enough to issue a request for additional proposals.

Newtown CDC pitched a design that prioritized efficient homes in order to keep prices low. It also made the homes part of a community land trust, a nonprofit entity that actually owns the land and creates a sale-like long-term lease of the home to keep its price far below the market rate. The purchasers get a good deal on the homes and share in the proceeds of any future sale, while the nonprofit continues to steward the property and maintain the affordable prices.

Newtown CDC won the project, and the city donated the land. Crummey partnered with local architectural design firm coLab Studio, whose principal, Matt Salenger, lives in the neighborhood. He says the concept of creating micro estates immediately brought to mind the Tim Burton film Big Fish, which is set in a fictional small town that seems to be almost magically tucked away in a forest.

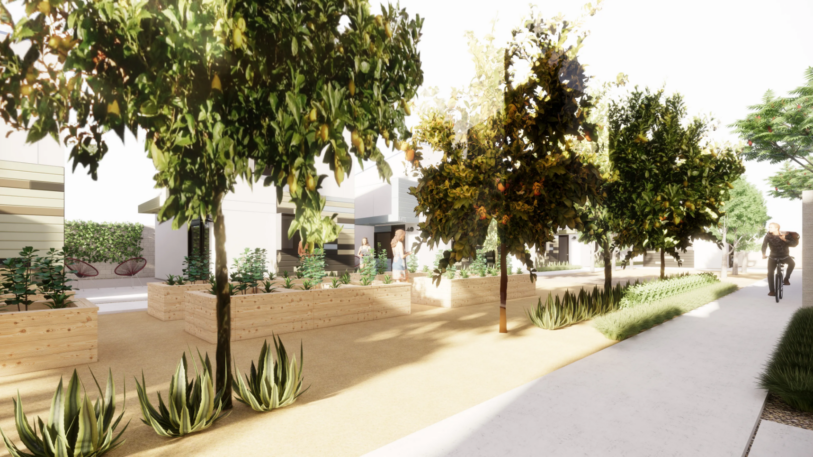

“The houses are aligned on a main street, but there’s no paving, just grasses and trees,” Salenger says. “David [Crummey] and I had a real connection about trying to make the landscape the thing that was first and foremost there.”

The project they built is reminiscent of that pavement-free community, with a large central open space lined with planters and trees, and small patio spaces between each home that lack any clear lines of ownership, encouraging more social interaction.

The homes themselves are also innovatively designed, with choices guided by keeping costs down while also providing comfortable living space. “Doors and glazing are one of the most expensive aspects of any building. So we limited it to one exterior door. There are four exterior windows. There’s only one interior door, for the bathroom, which is located under the stairs,” Salenger says. “We thought about every single inch.”

The homes have all been sold, each priced at $170,000, except for the ADA-compliant home, which was $210,000. Crummey says the homes were recently appraised at a value of $260,000. “At the most expensive, it’s a $50,000 below-market sale,” he says. And as part of the community land trust, the homes will continue to be priced below market, no matter when the current owners decide to sell.

“These are unique houses,” Salenger says. “There’s nothing like it in town.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.