While experts expected Vladimir Putin would put his nuclear forces on high alert at some point after the invasion of Ukraine and the U.S. has downplayed that action as posturing, the Russian leader’s actions have succeeded in making Americans more wary of a nuclear event now than at any time since the Cold War.

President Joe Biden, asked Monday whether U.S. citizens should be concerned about a nuclear war breaking out, gave a succinct answer: “No.” And Matthew Bunn, former adviser to President Bill Clinton’s Office of Science and Technology Policy, told Vox, “I think there is virtually no chance nuclear weapons are going to be used in the Ukraine situation. . . . No one outside of Putin’s inner circle knows for sure why Putin has taken this action. My guess—and it’s only that—is that it is intended as further signaling to deter anyone in the West from even thinking about intervening militarily to help Ukraine.”

Officials also point to the Aegis Ashore system, a ballistic missile defense system located on a base in Poland, as one form of protection.

But that hasn’t eased the curiosity about how prepared the U.S. is for a nuclear event—and what one should do in case of a blast.

In terms of preparation, it’s a mixed bag. The government’s Ready.gov site does have a page dedicated to a nuclear explosion, offering solid advice on what to do if you’re in the vicinity of one. Better still, the page isn’t an archive and has been updated in at least the past two years, as it notes the pandemic could cause some problems when it comes to finding shelter.

“While commuting, identify appropriate shelters to seek in the event of a detonation,” it suggests. “Due to COVID-19, many places you may pass on the way to and from work may be closed or may not have regular operating hours.”

The page also suggests bringing items to protect yourself and your family from COVID-19, such as masks and hand sanitizer, if you are evacuated.

On a local level, however, there’s less information. Of the major metro areas that are likely to be targeted in the event of an attack (Washington, D.C.; New York; Los Angeles; Chicago; San Francisco; Houston), only one of the emergency management department’s websites discusses preparing for a nuclear incident—Los Angeles. (New York and Washington, D.C., namecheck a radiation disaster, but only as a hazmat event.)

That’s led to some criticism about national preparedness levels. In 2018, the K=1 Project, Center for Nuclear Studies at Columbia University, said “the United States and its citizens are not currently prepared for the after effects of a nuclear disaster of any type, whether an air missile from another nation, an attack on the ground from a terrorist or terrorist group, or some kind of accidental detonation.”

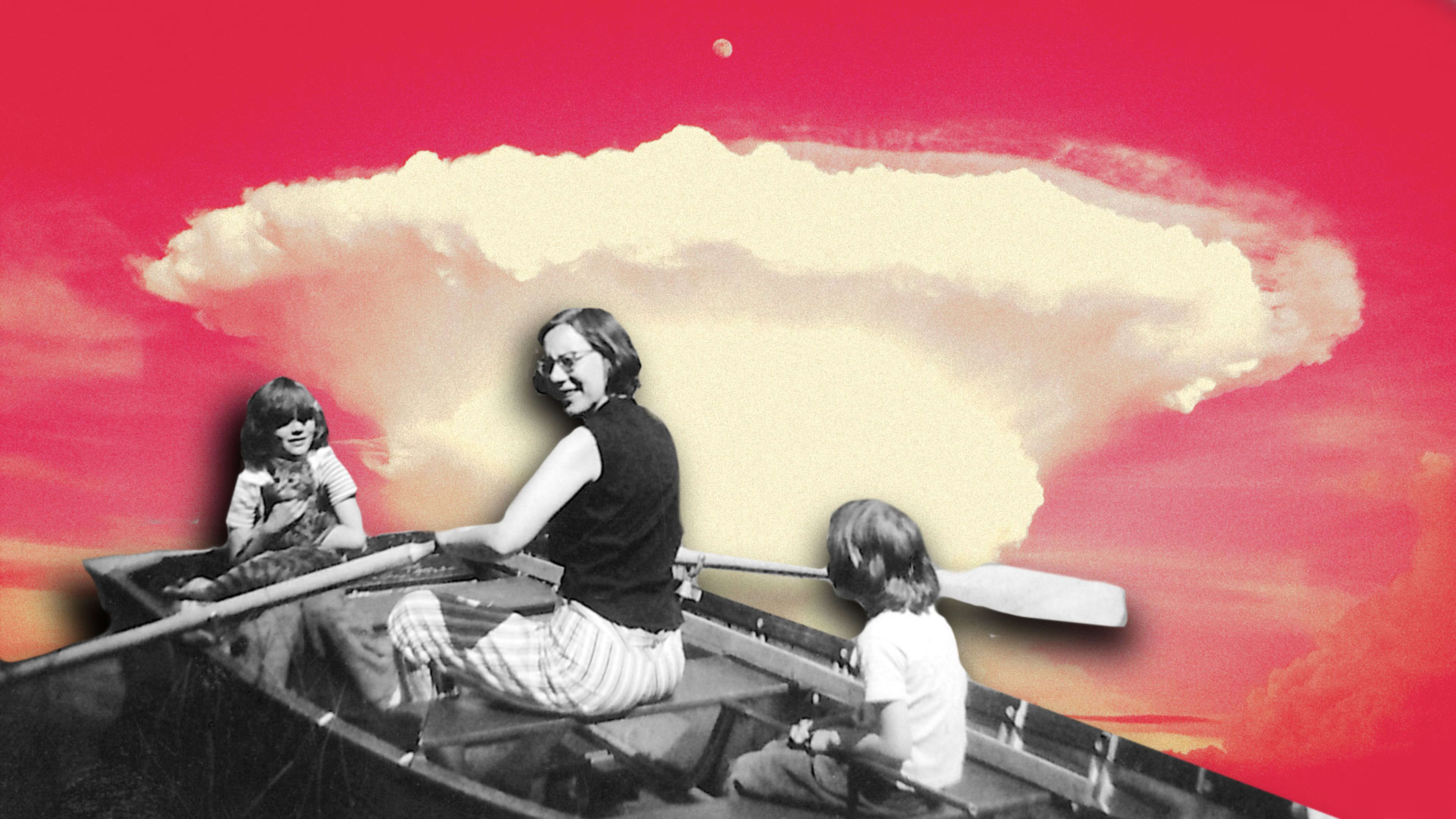

That’s chilling. But in the rare possibility of a nuclear event, whether a traditional attack as imagined in so many 1980s films or a dirty bomb, there are things you can do to protect yourself and increase your chances of survival. Irwin Redlener, a leader in disaster preparedness, gave some suggestions in a 2008 TED Talk, including to avoid looking at the explosion’s flash of light, which can cause blindness, and to follow the classic “duck and cover” advice given to Boomers and Gen-Xers in grade school to avoid getting injured by debris.

One thing that might cause a bit less anxiety amid this scare is remembering that threats like these have been made before—19 times since the end of World War II. (In fact, in 2014 the Kremlin made similar threats during the invasion and annexation of Crimea.) In each of those instances, the situation calmed down eventually. And White House and NATO officials are trying to dial back rhetoric in hopes that things can be deescalated once again.

“Nuclear-armed states can’t fight nuclear wars because it would risk their extinction, but they can and do threaten it,” Matthew Kroenig, a professor of government and foreign service at Georgetown University who specializes in atomic strategy, told The New York Times. “They play games of nuclear chicken, of raising the risk of war in hopes that the other side will back down and say, ‘Geez, this isn’t worth fighting a nuclear war over.'”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.